Abstract

Objective To estimate the frequency, duration, and clinical importance of postherpetic neuralgia after a first episode of herpes zoster.

Design Prospective cohort study with long term follow up.

Setting Primary health care in Iceland.

Participants 421 patients with a first episode of herpes zoster.

Main outcome measures Age and sex distribution of patients with herpes zoster, point prevalence of postherpetic neuralgia, and severity of pain at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months and up to 7.6 years after the outbreak of zoster.

Results Among patients younger than 60 years, the risk of postherpetic neuralgia three months after the start of the zoster rash was 1.8% (95% confidence interval 0.59% to 4.18%) and pain was mild in all cases. In patients 60 years and older, the risk of postherpetic neuralgia increased but the pain was usually mild or moderate. After three months severe pain was recorded in two patients older than 60 years (1.7%, 2.14% to 6.15%). After 12 months no patient reported severe pain and 14 patients (3.3%) had mild or moderate pain. Seven of these became pain free within two to seven years, and five reported mild pain and one moderate pain after 7.6 years of follow up. Sex was not a predictor of postherpetic neuralgia. Possible immunomodulating comorbidity (such as malignancy, systemic steroid use, diabetes) was present in 17 patients.

Conclusions The probability of longstanding pain of clinical importance after herpes zoster is low in an unselected population of primary care patients essentially untreated with antiviral drugs.

Introduction

This is the first prospective, long term follow up study addressing the clinical course of herpes zoster on the basis of an inception cohort of patients in primary care--that is, individuals with a first episode of zoster.[1 2] One primary aim was to classify patients' subjective experience of pain after zoster (postherpetic neuralgia). Most research on zoster is presently designed to evaluate the effect of antiviral treatment, and data from large scale prospective studies are scarce, especially regarding the severity or clinical importance of pain.[3-11]

Participants and methods

From 1990 to 1995 a network of 62 Icelandic general practitioners (catchment area 100 000 people) reported every new case diagnosed clinically as herpes zoster to the principal investigator, who was responsible for a structured evaluation and follow up. Sampling methods, exclusion and inclusion criteria, and strengths and weaknesses of the method have been described elsewhere.[7 8] In the present analysis, we excluded patients with a history of zoster.

The point prevalence of postherpetic neuralgia was collected at one, three, six, and 12 months after the start of the rash by asking patients (or parents) to rank any discomfort from the dermatome concerned as none, mild, moderate, or severe.[8]

Long term follow up (greater than 12 months from zoster) was conducted in two parts. Firstly, a random subsample of 183 patients who were pain free at one year follow up were contacted by telephone in April 1997 and questioned about possible recurrence of pain. Secondly, all 14 patients who had reported pain at 12 months were followed until January 1999, with special emphasis on the importance of neuralgic pain to activities of daily life. The study was approved by the national ethics committee.

Point prevalence, severity, and duration of pain were analysed according to sex and age. Point prevalence was analysed by logistic regression, severity by linear regression, and duration by Cox's regression. As there was no interaction between sex and age and as sex was not a significant predictor, we present the duration as Kaplan-Meier curves for two age groups. Significance testing was two sided at the 5% level. We used the software package SPIDA.[12] Confidence intervals were calculated with CIA software.[13]

Results

We recruited 421 patients with a first episode of zoster. End points were obtained for all patients at 12 months (table 1). Age was a significant predictor of pain at each time point after herpes zoster. The odds ratio per 10 years' age difference was 1.87 (95% confidence interval, 1.56 to 2.23) after one month, 2.11 (1.56 to 2.84) after 3 months, 2.45 (1.50 to 4.01) after 6 months, and 2.33 (1.48 to 3.69) after 12 months. Age was also a significant predictor of pain severity at one month (P = 0.02) and of pain duration (P [is less than] 0.001). Sex was not a significant predictor of postherpetic neuralgia at any point Patients younger than 60 years had a benign course (figure). After the age of 60, the frequency and severity of neuralgia increased, although pain was never classified as severe. Potentially immunomodulating comorbidity (such as malignancy, systemic steroid use, and diabetes) was present at diagnosis or developed within 12 months in 17 patients (see table 2 in full version).

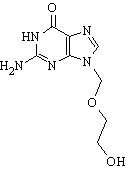

[Figure ILLUSTRATION OMITTED]

Table 1 Point prevalence and severity of postherpetic neuralgia one, three, and 12 months after start of herpes zoster in different age groups

(*) Owing to prospective design, only those are counted here who were reached within our weeks of planned date of follow up. Of the four patients not accounted for at 12 months, three had died and one had moved abroad.

Seventeen patients (4.0%) were treated with antiviral drugs during the zoster rash; their mean age was 60.6 years (range 43.4 to 89.3 years). Fourteen of these received doses considered subtherapeutic today (200 mg to 500 mg of aciclovir five times daily). Three patients (0.7%) were treated with therapeutic doses, one with aciclovir 800 mg five times daily and two by intravenous treatment. Of the treated patients, seven had ophthalmic zoster, one oticus zoster, one suspected viral meningitis, and the remainder cutaneous zoster. None of the random subsample of 183 patients who were free of neuralgia at 12 months reported a recurrence of pain in the 3.2 to 7.0 year follow up period (860 person years).

After 12 months 14 patients (3.3%) still reported mild or moderate pain; most of them (12/14) classified the discomfort as mild. One patient with mild pain was subsequently lost to follow up. The 13 patients with neuralgia at 12 months (see table 3 in full version) were followed for a mean of 6.3 years (range 3.5 to 7.6 years or 79.4 person years). Seven of these became pain free within two to seven years. Five reported mild postherpetic neuralgia, one reported moderate postherpetic neuralgia, and no patient reported severe neuralgia at the end of follow up.

Discussion

Our study shows that the clinical course of herpes zoster is relatively benign and that postherpetic neuralgia rarely affects daily life. When it occurs, neuralgia can last for years, but it may disappear after several years.

The diagnostic methods used in this study reflect the reality of everyday practice, an approach advocated by experts in evidence based medicine.[14] As recommended by a recent consensus, we included clinically important pain at three months as a primary end point.[9 15]

The use of different variables to follow the course of zoster (for example, different pain measurements, viral shedding, healing of rash) makes comparison between studies difficult. A significant difference need not be clinically important. Many studies have recorded pain simply as any pain, without differentiating the severity.[16] It is difficult to judge the clinical relevance of these data, and we believe that they tend to overestimate the problem of postherpetic neuralgia. Our results agree with those of the placebo group in McKendrick et al's study, in which the prevalence of postherpetic neuralgia three months after zoster was 24% (20% in our study) among 181 patients aged 60 or more.[17]

It is debatable whether antiviral treatment in acute zoster reduces the risk of postherpetic neuralgia. A recent meta-analysis suggests that there might be some effect.[16] Some guidelines recommend antiviral drugs in patients aged 60 or more,[18] others in patients aged 50 or more,[19] a recommendation which is not supported by our data. Other risk factors for postherpetic neuralgia have been put forward: extent of pain at onset, extent of rash, severity and duration of preherpetic neuralgia, and possibly psychosocial status and sex.[7 20-22] One study suggests that the optimal treatment of symptoms in the acute phase of zoster may reduce the risk of postherpetic neuralgia.[23]

If zoster is to be treated appropriately, its clinical course needs to be fully understood. Existing evidence does not support the routine use of antiviral treatment in herpes zoster.

What is already known on this topic

Herpes zoster affects all age groups

The acute phase may be followed by longstanding neuralgia; antiviral drugs are commonly advocated to alleviate this phase, and they are believed to reduce the risk of postherpetic neuralgia

What this study adds

The probability of clinically important postherpetic neuralgia is low; the risk of longstanding pain has been overemphasised in trials of drug treatments

Once a patient becomes free of pain after a zoster episode, there is practically no risk of pain recurrence. Once present, neuralgia can persist for years, but spontaneous remission may occur after several years

There may be an indication for antiviral drugs in patients aged more than 60 to prevent postherpetic neuralgia, but more data on risk factors for neuralgia are needed

We thank the general practitioners who helped with the study, Linn Getz for editing the paper, and Helgi Sigvaldason for statistical advice.

Contributors: SH conceived the idea, outlined the study design, gathered information from the patients, and analysed the data. GP, initially as a medical student, participated in the follow up and analysis of data in 1997-9. SG and JAS contributed to the design and analysis. The paper was mainly written by SH and JAS, but all authors contributed to its preparation. SH and JAS are guarantors.

Funding: This study was partially funded by the Icelandic College of Family Physicians and the Research Fund of the University of Iceland.

Competing interests: SH has received honoraria from Glaxo-Wellcome for lecturing on herpes zoster.

[1] Sackett DL, Hayens RB, Guyatt GH, Tugwell P. In: Clinical epidemiology: a basic science for clinical medicine, 2nd ed. Boston: Little, Brown, 1991:318.

[2] Hayens B, Sackett D. Purpose and procedure. Evidence-based Med 1998;3:130-1.

[3] Sanders HWA. Herpes zoster in de huisartspraktijk. Doctoral thesis, Nijmegen: University of Nijmegen, 1968.

[4] Hope-Simpson RE. Postherpetic neuralgia. J R Coll Gen Pract 1975;25:571-5.

[5] Christensen P, Norrelund N. Herpes zoster in general practice. Ugeskr Laeger 1985;147:3401-3.

[6] Ragozzino MW, Melton LJ, Kurland LT, Chu CP, Perry HO. Risk of cancer after herpes zoster. N Engl J Med 1982;307:393-7.

[7] Helgason S, Sigurdsson JA, Gudmundsson S. The clinical course of herpes zoster: a prospective study in primary care. Eur J Gen Pract 1996;2:12-6.

[8] Petursson G, Helgason S, Gudmundsson S, Sigurdsson JA. Herpes zoster in children and adolescents. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1998;17:905-8.

[9] Dworkin RH, Carrington D, Cunningham A, Kost RG, Levin MJ, McKendrick MW, et al. Assessment of pain in herpes zoster: lessons learned from antiviral trials. Antiviral Res 1997;33:73-85.

[10] Lydick E, Epstein RS, Himmelberger D, White CJ. Herpes zoster and quality of life: a self-limited disease with severe impact. Neurology 1995;45(suppl 8):52-3.

[11] Lancaster T, Silagy C, Gray S. Primary care management of acute herpes zoster: systematic review of evidence from randomized controlled trials. Br J Gen Pract 1995;39-45.

[12] Gebsky V, Seung D, McNeil D, Linn D. SPIDA user's manual, version 6. NSW, Australia: Statistical Computing Laboratory, Macquarie University, 1992.

[13] Gardner MJ, Altman D. Confidence Interval Analysis (CIA). Statistics with confidence. London: BMJ Publishing Group, 1989.

[14] Knottnerus JA, Dinant GJ. Medicine based evidence, a prerequisite for evidence based medicine: further research methods must find ways of accommodating clinical reality, not ignoring it. BMJ 1997;315:1109-10.

[15] Kay R. Some fundamental statistical concepts in clinical trials and their application in herpes zoster. Antivir Chem Chemother 1995;6(suppl 1):28-33.

[16] Jackson JL, Gibbons R, Meyer G, Inouye L. The effect of treating herpes zoster with oral acyclovir in preventing postherpetic neuralgia. A meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med 1997;157:909-12.

[17] McKendrick MW, McGill JI, Wood MJ. Lack of effect of acyclovir on postherpetic neuralgia. BMJ 1989;298:431.

[18] Johnson RW. Current and future management of herpes zoster. Antivir Chem Chemother 1997;8(suppl 1):19-31.

[19] Kost RG, Straus SE. Postherpetic neuralgia--pathogenesis, treatment, and prevention. N Engl J Med 1996;335:32-42.

[20] Beutner KR, Friedman DJ, Forszpaniak C, Andersen PL, Wood MJ. Valaciclovir compared with acyclovir for improved therapy for herpes zoster in immunocompetent adults. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1995;39:1546-53.

[21] Dworkin RH, Hartstein G, Rosner HL, Walther RR, Sweeney EW, Brand L. A high-risk method for studying psychosocial antecedents of chronic pain: the prospective investigation of herpes zoster. J Abnorm Psychol 1992;101:200-5.

[22] Bowsher D. The lifetime occurrence of herpes zoster and prevalence of post-herpetic neuralgia: a retrospective survey in an elderly population. Eur J Pain 1999;3:335-42.

[23] McQuay HJ. Antidepressants and chronic pain. Effective analgesia in neuropathic pain and other syndromes. BMJ 1997;314:763-4.

(Accepted 25 April 2000)

Editorial by Cunningham

Arbaer Health Care Centre, IS-110 Reykjavik, Iceland

Sigurdur Helgason general practitioner

Department of Family Medicine, University of Iceland, IS-105 Reykjavik, Iceland

Gunnar Petursson medical doctor

Johann A Sigurdsson professor

Directorate of Health, IS-150 Reykjavik, Iceland

Sigurdur Gudmundsson medical director of health

Correspondence to: S Helgason sh@ centrum.is

BMJ 2000;321:794-6

bmj.com

A fuller version of this article, with extra tables, appears on the BMJ website. This article is part of the BMJ's trial of open peer review, and documentation relating to this also appears on the website

COPYRIGHT 2000 British Medical Association

COPYRIGHT 2000 Gale Group