Abstract

We describe the case of a patient with a parotid mass that was found to consist of both a facial nerve schwannoma and a monomorphic adenoma. To our knowledge, this is the first report of these two lesions presenting as a single tumor. We also discuss the incidence, diagnosis, and treatment of parotid facial nerve schwannomas.

Introduction

A schwannoma can arise along any peripheral nerve. Approximately 25% of all schwannomas occur in the head and neck, and the vast majority of these occur along the vestibular portion of cranial nerve VIII. (1,2) Schwannomas occasionally originate in the facial nerve; in such cases, the intratemporal portion is most likely to be affected. (3) Schwannomas of the peripheral facial nerve are quite rare.

In this article, we describe an unusual case of a schwannoma that arose from the peripheral facial nerve and that was associated with a monomorphic adenoma of the parotid. To our knowledge, this is the first description of the simultaneous appearance of a peripheral facial nerve schwannoma and a monomorphic adenoma of the parotid.

Case report

A 54-year-old Filipino man presented with a slowly enlarging left preauricular mass of 2 years' duration. He was otherwise healthy and had no history of facial or neck masses or skin malignancy. On examination, the 2 x 2-cm mass was located anterior to the left tragus. It was firm, nontender, and mobile. No other masses were noted on the head and neck, and the facial nerve was intact throughout all its branches.

Fine-needle aspiration cytology revealed that the mass contained hypocellular material that featured a few clusters of bland-appearing cells with vesicular and round-to-elongated nuclei, ill-defined cell borders, and moderate-to-abundant cytoplasm on a background of blood. These features suggested, hut were not entirely diagnostic of, a pleomorphic adenoma. Computed tomography (CT) revealed that the well-circumscribed, nonenhancing mass in the left parotid gland was consistent with a pleomorphic adenoma (figure 1).

[FIGURE 1 OMITTED]

The patient underwent a left parotidectomy with facial nerve dissection. Dissection of the inferior division was uneventful. Upon dissection of the superior division, a lobulated cystic lesion with a mottled purple color was noted. The mass was densely adherent to the facial nerve and extended to the deep lobe of the parotid gland. With difficulty, the mass was separated from the epineurium of the superior division of the facial nerve. During the course of the dissection, the frontal branch of the nerve was transected, and a graft from the ipsilateral great auricular nerve was used to repair it. The remainder of the mass was dissected free from the deep lobe of the parotid.

At the 2-week follow-up, the patient exhibited paralysis of the frontal branch of the left facial nerve, but all other branches were intact.

During the resection, a biopsy specimen obtained from the left parotid gland was sent to pathology for an intraoperative frozen-section diagnosis. The material was not diagnostic, and a second sample was sent. Histologically, the second sample appeared to consist of cellular mesenchymal tissue with a focal area of cartilaginous differentiation. A diagnosis of pleomorphic adenoma was again made. Immunohistochemical staining for actin and keratin was ordered on the unfrozen tissue.

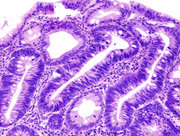

Subsequently, the left superficial parotid gland specimen was obtained in fragments for permanent sections. The largest fragment measured 5.0 x 4.0 x 2.0 cm in aggregate, and a suture marked the area that had been biopsied. Grossly, the parotid gland was made up of yellow-tan fibrofatty tissue with no identifiable lesions or nodules. Histologically, a tumor consisting of compact spindle cells arranged in intersecting fascicles was identified (figure 2, A). The tumor could be seen budding from a branch of the facial nerve (figure 2, B). A diagnosis of benign schwannoma was made. Almost the entire tumor exhibited the Antoni A pattern, with a few focal areas showing nuclear palisading and Verocay's bodies. An S-100 immunohistochemical stain was diffusely positive, supporting the diagnosis of a schwannoma (figure 2, C). The stains for actin and keratin were negative, ruling out a pleomorphic adenoma. Additionally, a separate and clinically unapparent encapsulated epithelial proliferation consistent with a monomorphic adenoma was discovered (figure 3). The adenoma contained bland-appearing cells with darkly staining nuclei arranged in a glandular pattern.

[FIGURES 2-3 OMITTED]

At the 7-month follow-up, the patient continued to experience left frontal nerve paralysis.

Discussion

Some 82% of all parotid tumors are benign; of these, 57% are pleomorphic adenomas. (4) Neuromas are uncommon benign parotid tumors; they include schwannomas (neurilemmomas) and neurofibromas, although both originate in Schwann's cells. A schwannoma is a solitary encapsulated tumor; a neurofibroma is not capsulated and contains nerve fibers within the lesion. Therefore, it is theoretically possible to dissect a schwannoma free from its associated nerve, whereas such is not possible with a neurofibroma. Additionally, although malignant transformation is rare with both tumors, it is more likely to occur with a neurofibroma.

Schwannomas can occur in any part of the body. Between 25 and 48% are located in the head and neck; the vestibular nerve is the most likely site. (1,5) In 1967, Oberman and Sullenger (6) reported that schwannomas occur more often in women than in men, but Conley and Janecka (7) reported in 1975 that these lesions were equally distributed between the sexes. Schwannomas usually occur during the third and fourth decades of life. In a study of 400 consecutive parotidectomies at Singapore General Hospital, Chong et al found that 5 patients (1.3%) had facial nerve schwannomas. (8) Intracranial facial nerve schwannomas are found approximately 9 times more often than are extracranial schwannomas. (3)

The presenting signs and symptoms of schwannomas of the head and neck vary dramatically according to the tumor's precise location. These tumors usually grow eccentrically from the nerve sheath and do not contain nerve fibers intramurally. Therefore, they do not directly impede nerve function. Within the parotid gland, schwannomas may reach significant size without causing any clinical symptoms. (9,10) This is in contrast to intracranial schwannomas; with these lesions, the bony confines and limited space available for tumor extension often result in earlier neurologic sequelae secondary to nerve compression. Therefore, tumors that arise from the intratemporal portion of the facial nerve usually cause progressive facial paralysis, tinnitus, vertigo, or hearing loss. (11) In contrast, peripheral tumors often present as parotid masses or with pain, and in 20% of cases, they may cause gradual-onset facial weakness. (12)

The case we report here illustrates the difficulty of establishing a preoperative--and even intraoperative--pathologic diagnosis of a salivary gland lesion. The diagnosis may be suggested by findings on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and confirmed by microscopic examination. Schwannomas exhibit strong enhancement on gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted imaging. On T2-weighted imaging with high spatial resolution, facial nerve schwannomas appear as hypointense, round masses. (13) However, MRI is rarely obtained for routine parotid masses, and it is generally contended that no preoperative imaging is cost-effective in this situation. We ordered CT for our patient so that we could further evaluate the lesion, which was necessary because the results of fine-needle aspiration cytology were inconclusive. A review of the literature reveals that the findings of fine-needle aspiration of parotid schwannomas are often inconclusive; if anything, they are suggestive of pleomorphic adenomas, as occurred in our case. (8,14-18) The schwannoma in our patient was difficult to diagnose because of the paucity of tumor cells in the aspirate and the high degree of cellular pleomorphism.

Histopathologically, a schwannoma is characterized by Antoni A and B patterns. An Antoni A pattern is characterized by elongated and spindle-shaped Schwann's cells arranged in short bundles or interlacing fascicles with nuclear palisading, whorling of the cells, and Verocay' s bodies. Verocay's bodies are formed from two compact rows of well-aligned nuclei and cell processes that are arranged in a roughly oval shape. The less-cellular Antoni B pattern features varying degrees of cellular pleomorphism; irregular cell types are scattered in loose connective tissue with no definable palisading of the tumor cell nuclei. (19) Antoni A and B patterns usually coexist, although their respective proportions may vary.

It is interesting that in our patient, the parotid schwannoma, itself a rare tumor, was found with another rare parotid tumor, a monomorphic adenoma. Monomorphic adenomas are benign epithelial growths that appear in a regular, usually glandular, pattern. This tumor is distinguishable from a pleomorphic adenoma by the regular pattern and by a lack of mesenchymal-like tissue. Both sehwannomas and monomorphic adenomas exhibit no propensity toward multicentricity or bilaterality. We believe that their coexistence in the superficial lobe of the parotid gland in our patient was merely coincidence.

Treatment of both tumors involves surgical excision with a margin of normal parotid tissue. For a schwannoma, meticulous dissection of the tumor from the involved nerve requires the use of a microscope, and surgery frequently causes nerve damage. Although making a preoperative diagnosis of a peripheral facial nerve schwannoma is rare, it does present a dilemma for a patient with normal nerve function. The patient must be advised that nerve paralysis is a likely outcome that might require subsequent nerve grafting. Postponing surgery may be appropriate if the patient prefers to delay nerve injury. Nevertheless, the patient should be informed that as the schwannoma enlarges, its eventual excision will become more difficult and the likelihood of nerve injury will increase.

References

(1.) Putney FJ, Moran JJ, Thomas GK. Neurogenic tumors of the head and neck. Laryngoscope 1964;74:1037-59.

(2.) Katz AD, Passy V, Kaplan L. Neurogenous neoplasms of major nerves of face and fleck. Arch Surg 1971;103:51-6.

(3.) Liliequist B, Thulin CA, Tovi D, et al. Neurinoma of the labyrinthine portion of the facial nerve. Case report, J Neurosurg 1972; 37:105-9.

(4.) Chung YF, Khoo ML, Heng MK, et al. Epidemiology of Warthin's turnout of the parotid gland in an Asian population. Br J Surg 1999;86:661-4.

(5.) Williams HK, Cannell H, Silvester K, Williams DM. Neurilemmorea of the head and neck. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1993;31: 32-5.

(6.) Oberman HA, Sullenger G. Neurogenous tumors of the head and neck. Cancer 1967;20:1992-2001.

(7.) Conley J, Janecka IP. Neurilemmoma of the head and neck. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol 1975;80:459-64.

(8.) Chong KW, Chung YF, Khoo ML, et al. Management of intraparotid facial nerve schwannomas. Aust N Z J Surg 2000;70: 732-4.

(9.) Neely JG, Alford BR. Facial nerve neuromas, Arch Otolaryngol 1974;100:298-301.

(10.) Avery AP, Sprinkle PM, Benign intraparotid schwannomas. Laryngoscope 1972;82:199-203.

(11.) Pulec JL. Facial nerve neuroma. Ear Nose Throat J 1994;73:721-2, 725-39, 743-52.

(12.) Bretlau P, Melchiors H, Krogdahl A. Intraparotid neurilemmoma. Acta Otolaryngol 1983;95:382-4.

(13.) Jager L, Reiser M. CT and MR imaging of the normal and pathologic conditions of the facial nerve. Eur J Radiol 2001;40:133-46.

(14.) Jayaraj SM, Levine T, Frosh AC, Almeyda JS. Ancient schwannoma masquerading as parotid pleomorphic adenoma. J Laryngol Otol 1997;111:1088-90.

(15.) Cunningham LL, Jr., Warner MR. Schwannoma of the vagus nerve first diagnosed as a parotid tumor. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2003;61:141-4.

(16.) Oncel S, Onal K, Ermete M, Uluc E. Schwannoma (neurilemmoma) of the facial nerve presenting as a parotid mass. J Laryngol Otol 2002;116:642-3.

(17.) Gupta RK, Dowle CS. A case of neurilemoma (schwannoma) that mimicked a pleomorphic adenoma (an example of potential pitfall in aspiration cytodiagnosis). Diagn Cytopathol 1991;7: 622-4.

(18.) Prager TM, Klesper B. Neurinoma of the facial nerve mimicking a parotid tumour. A case report. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1998; 27:370-1.

(19.) Segas JV, Kontrogiannis AD, Nomikos PN, et al. A neurilemmoma of the parotid gland: Report of a case. Ear Nose Throat J 2001;80:468-70.

>From the Division of Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery, Department of Surgery (Dr. Richmon and Dr. Chia), and the Department of Pathology (Dr. Wahl), University of California, San Diego School of Medicine.

Reprint requests: Jeremy Richmon, MD, Division of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, School of Medicine, University of California San Diego, 200 W. Arbor Dr., Mail Code 8895, San Diego, CA 92103. Phone: (619) 543-5910; fax: (858) 534-5922: e-mail: jrichmon@hotmail.com

COPYRIGHT 2004 Medquest Communications, LLC

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group