Abstract

Gingival diseases are the most widely held diseases in America. In some patients, periodontal disease appears in a generalized form, but more often it appears in localized areas. Furthermore, after treatment with scaling and root planing (SRP) in generalized cases, the disease is often reduced to a few local areas in the patient's mouth. Since periodontitis is a bacterial infection with known pathogenic microorganisms, the local delivery of antimicrobials has been considered to be a possible solution for treating and controlling localized forms of periodontal disease.

Three current local chemotherapeutic agents are reviewed in this paper: doxycycline gel, chlorhexidine chip and minocycline microspheres. With the advancement of local drug delivery systems, clinicians and their patients have new alternatives for treatment of periodontal disease.

Introduction

Since the early experimental gingivitis studies in the 1960s, the consensus of clinical research supports the concept that the initiation and progression of periodontal disease is due to bacterial plaque and its metabolic by-products. (1-3) Epidemiological studies have also demonstrated that periodontal disease is a site specific process, rather than the previous model of a generalized destruction of the periodontium. (4,5) With a site specific model of destruction, treatment can then be concentrated in those sites demonstrating breakdown rather than attempting to treat the whole dentition.

A bacterial etiology for periodontal disease provides an opportunity for an antimicrobial approach to treatment. Systemic therapy has demonstrated success in periodontal diseases such as aggressive periodontitis (specifically the former juvenile and refractory periodontitis), where precise bacterial species have been identified. (6,7) However, for generalized chronic (formerly adult) periodontitis, systemic antibiotic therapy has demonstrated little clinical efficacy. (8,9) Additionally, in contrast to local chemotherapeutics, systemic antibiotic usage presents the risk of producing antibiotic resistant bacterial strains. (3)

Several local delivery antimicrobial systems have demonstrated clinical efficacy. Tetracycline, doxycycline, minocycline and metronidazole have all been formulated in a local delivery system. (3,10-15) Along with the above traditional antibiotics, the topical antimicrobial, chlorhexidine, has been formulated for local delivery at subgingival sites as well. (16-18)

Scaling and Root Planing

Periodontitis is usually treated with scaling and root planing (SRP) as an initial therapy to remove subgingival plaque and calculus. (19-21) SRP generally reduces probing depths (PD), increases gain in clinical attachment levels (CAL) and can decrease disease progression. (20-23) Sites initially 4 to 6 mm have averaged 1.29 mm reduction with 0.55 mm of attachment gain, while sites 7 mm or greater demonstrate an average of 2.16 mm reduction with 1.29 mm attachment gain. (20)

Unfortunately the effectiveness of removing subgingival deposits decreases with increasing probing depths. (24,25) It has been demonstrated that when probing depths exceed 5 mm, complete root debridement occurs only 32% of the time. (24) Although mechanical therapy is effective for the majority of periodontal patients, it rarely results in complete removal of periodontal pathogens. (19-25) Local chemotherapeutics have been developed to augment traditional SRP.

Three agents currently used in clinical practices are reviewed in this paper: doxycycline gel, chlorhexidine chip and minocycline microspheres. With the advancement of local drug delivery systems, dentists and hygienists have new alternatives for treatment of periodontal disease. Local chemotherapeutic agents offer an additional mode of therapy and should be used on a case-to-case basis, not necessarily as an initial treatment.

Doxycycline Gel (Atridox[TM])

Atridox[TM]--CollaGenex Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Newton, PA 18940 (1-888-339-5678)

Atridox[TM] is a biodegradable gel containing 10% by weight doxycycline. (26) The medicament is supplied in two syringes that must be mixed together chairside for 25 repetitions (approximately 30 seconds) (Figure 1). The mixed solution is placed into one syringe where it is placed to the depth of the pocket. The solution is expressed until it overfills the pocket and begins to set (Figure 2). Upon contact with the moist environment, the liquid rapidly solidifies. The residual polymer can then be packed into the pocket using the underside of a curette. Treatment areas should not be brushed or flossed for one week.

Garrett et al. published a study in 1999 that evaluated the effectiveness of Atridox in 822 moderate to severe periodontitis patients. (27) They compared doxycycline polymer (8.5%) to placebo control, oral hygiene, and SRP in two multicenter sites. After nine months the authors concluded that Atridox alone produced the largest decrease in probing depth at 1.2 mm, as compared with the oral hygiene group (0.6 mm), the placebo group (0.8 mm) and the SRP group (1.1 mm). Mean increase in CAL for the Atridox group was 0.8 mm, superior to the oral hygiene group (0.4 mm), the placebo group (0.4 mm) and the SRP group (0.7 mm). (27)

Chlorhexidine Chip (PerioChip[R])

PerioChip[R]--Dexcel Pharm, Edison, NJ 08837 (1-866-737-4624)

Chlorhexidine (CHX) was introduced in the 1970s as a topical antimicrobial. (28) Since then it has developed into a powerful antiseptic capable of reducing plaque by 25 to 40% when used as a rinse or irrigation, respectively. (29) CHX has a specific mechanism of action against bacteria. (29) The positively charged, long chain molecule attaches to the negatively charged cell wall of the bacteria, disrupting the cell wall membrane. The cell wall ruptures with loss of the cytoplasm, resulting in cell death. (29)

The CHX chip is a 4 x 5 mm biodegradable film of hydrolyzed gelatin containing 2.5mg of chlorhexidine gluconate (30) (Figure 3). The chip is easily placed into periodontal pockets greater than 5 mm and requires no retentive system (Figure 4). The body resorbs the chip in eight to ten days.

The main adverse effects of CHX rinse are staining of the teeth, calculus formation, and altered taste sensation. However, few anaphylactic and allergic reactions have occurred in patients mainly of Japanese descent. (31) When CHX is employed in a chip, minimal side effects are induced. Most notable is a tendency for patients to complain of toothache or tooth sensitivity. (28) The CHX chip does not visibly stain the teeth. (28)

Chlorhexidine is delivered from the chip into the gingival sulcus at a concentration above 125 [micro]g/ml for at least seven days. (32) At this concentration, the mean percentage of subgingival bacteria inhibited in vitro was 99%. (33)

Studies have shown that the CHX chip can significantly improve gingival health when used as an adjunct to SRP. (33,34) Jeffcoat et al. reported on a total of 447 patients. (34) At nine months, the CHX chip treatment group had significant reductions in PD with respect to the two control groups (CHX + SRP, 0.95 mm; SRP, 0.65 mm; Placebo chip + SRP, 0.69 mm). The CHX chip treatment group also showed significant reductions in CAL with respect to the two control groups (CHX + SRP, 0.75 mm; SRP, 0.58 mm; Placebo chip + SRP, 0.55 mm). Furthermore, 19% of patients in the CHX chip group experienced a significant PD reduction from baseline of 2 mm or more at nine months as compared to the SRP group (8%). (34)

A later study evaluated the effect of CHX on alveolar bone height after nine months. (35) Radiographs of 45 patients were taken via quantitative digital subtraction radiography. Interestingly, 25% of sites treated with SRP and the CHX chip experienced bone gain. Conversely, 15% of the subjects treated with SRP alone continued to lose bone in one or more sites over the period of the study. (35)

Studies on the CHX chip demonstrate that it is a safe and effective adjunctive chemotherapy for the treatment of periodontal disease. Adverse effects to CHX chip placement have been minimal.

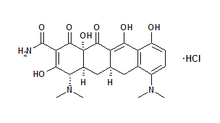

Minocycline Microspheres (Arestin[TM])

Arestin[TM] OraPharma, Inc, Warrminster, PA 18974 (1-215-956-2200)

Arestin[TM] is a microencapsulated minocycline hydrochloride in a bioabsorbable polymer (Figure 5) resulting in microspheres that are injected (Figure 6) in a powdered form into periodontal pockets. (19) Arestin administration results in local antibiotic concentrations of 340 [micro]g/ml for up to 14 days. (19)

In a study of 748 patients, Williams et al. reported that Arestin plus SRP resulted in mean probing depth reductions of 1.32 mm for SRP plus Arestin compared to 1.08 mm with SRP alone. (19) Additionally, the mean percentages of sites with greater than or equal to 2 mm of probing depth reduction was 40.52% for the SRP + Arestin group vs. 32.87% for the SRP alone group. (19) Due to the limits of clinical accuracy with a periodontal probe, it is important to note that the "2 mm threshold" is the gold standard clinicians use to monitor disease progression. Therefore, any adjunct that can increase the percentage of sites responding with a 2 mm probing reduction is significant.

Clinical trials demonstrate that Arestin is easy to place, is safe and efficacious. Adverse effects are minimal.

Discussion

With the advancement of local drug delivery systems, clinicians and their patients have new alternatives for treatment of periodontal disease. Local chemotherapeutic agents offer an additional mode of therapy and should be used on a case-to-case basis, not necessarily as an initial treatment. No other treatment has proven as beneficial as oral hygiene instructions and conventional scaling and root planing. For the majority of patients, periodontal sites will respond adequately to scaling and root planing and require no additional therapy. The use of local drug delivery systems in those situations would be considerable over treatment. Therefore, after thorough scaling and root planing local antimicrobial therapy should be used after a thorough re-evaluation, and only if a possibility to reduce the need for periodontal surgery exists.

Conclusion

Three local chemotherapeutic agents have been reviewed: Atridox[TM], a doxycycline gel, PerioChip[R], a chlorhexidine chip and Arestin[TM], a minocycline microspheres. All three are proven adjuncts that can improve the clinical response to traditional scaling and root planing.

References

(1.) Loe H, Theilade E, Jensen SB. Experimental gingivitis in man. J Periodontol 1965; 36:177-181.

(2.) Theilade E, Wright WH, Jensen SB, Loe H. Experimental gingivitis in man. II. A longitudinal clinical and bacteriological investigation. J Periodont Res 1966; 1:1-4.

(3.) Ciancio SG. Site specific delivery of antimicrobial agents for periodontal disease. General Dentistry 1999; 47(2): 172-181.

(4.) Haffajee AD, Socransky SS. Attachment level changes in destructive periodontal diseases. J Clin Periodontol 1986; 13(5): 461-475.

(5.) Socransky SS, Haffajee AD, Goodson JM, Lindhe J. New concepts of destructive periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol 1984; 11 (1): 21-32.

(6.) Slots J, Rosling BG. Suppression of the periodontopathic microflora in localized juvenile periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol 1983; 10:565-486.

(7.) van Winkelhoff AJ, Tijof CJ, de Graft J. Microbiological and clinical results of metronidazome plus amoxicillin therapy in Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans associated periodontitis. J Periodontol 1992; 63:52-57.

(8.) Listgarten MA, Lindhe J, Hellden L. Effect of tetracycline and/or scaling on human periodontal disease. Clinical, microbiological, and histopathological observations. J Clin Periodontol 1978; 5:246-271.

(9.) Scopp IW, Froum SJ, Sullivan M, Kazandijan G, Wank D, Fine, A. Tetracycline: A clinical study in human gingival tissue in patients with chronic periodontal disease. J Periodontol 1980; 51:328-330.

(10.) Tonetti M, Cugini AM, Goodson JM. Zero order delivery with periodontal placement of tetracycline loaded ethylene vinyl acetate fibers. J Periodontol Res 1990; 25:243-247.

(11.) Goodson JM, Cugini MA, Kent RL, et al. Multicenter evaluation of adjunctive tetracycline fiber therapy used in conjunction with scaling and root planing in maintenance patients: Clinical results. J Periodontol 1994; 65:685-691.

(12.) Poison AM, Southard GL, Dunn RL, et al. Periodontal pocket treatment in beagle dogs using subgingival Doxycyline from a biodegradable system. I. Initial clinical responses. J Periodontol 1996; 67: 1176-1184.

(13.) Larsen T. Occurance of doxycyclineresistant bacteria in the oral cavity after administration of doxycycline in patients with periodontal disease. Scand J Infect Dis 1991; 23:89-95.

(14.) Van Steenberghe D, Bercy P, Kohl J. Subgingival minocycline hydrochloride ointment in moderate to severe chronic adult periodontitis: A randomized, doubleblind, vehicle-controlled, multicenter study. J Periodontol 1993; 64:637-644.

(15.) Ainamo J, Lie T, EIlingsen BH, Hansen BF, Johansson LA, Karring T, et al. Clinical responses to subgingival application of a metronidazole 25 percent gel compared to the effect of subgingival scaling in adult periodontitis. J Clinic Periodontol 1992; 19:723-729.

(16.) Stabholz A, Soskoline W, Freidman M, et al. The use of sustained release delivery of chlorhexidine for the maintenance of periodontal pockets: A two-year clinical trial. J Periodontol 1991;62:429-433.

(17.) Stabholz A, Sela M, Freidman M, et al. Clinical and microbiological effects of sustained release chlorhexidine in periodontal pockets. J Clin Periodontol. 1986; 13:783-788.

(18.) Palcanis K, Weathefford T, Reese M, et al. Biodegradable chlorhexidine gelatin chip for the treatment of adult periodontitis: Effect on alveolar bone. J Dent Res 1997; 76 (Special issue): 152 Abst 167.

(19.) Williams RC, Paquette DW, Offenbacher S, et al. Treatment of periodontitis by local administration of minocycline microspheres: A controlled trial. J Periodontol 2001 ; 72:1535-1544.

(20.) Cobb CM. Nonsurgical pocket therapy: Mechanical. Ann Periodontol 1996; 1:443-490.

(21.) Haffajee AD, Cugini MA, Dibart S, et al. The effect of SRP on the clinical and microbiological parameters of periodontal diseases. J. Clin Periodontol. 1997; 24: 324-334.

(22.) Greenstein G. Nonsurgical periodontal therapy in 2000: A literature review. JADA 2000; 131:1580-1592.

23. Greenstein G. Periodontal response to mechanical nonsurgical therapy: A review. J Periodontal 1992; 63:(2): 118-130.

(24.) Caffesse RG, Sweeney PL, Smith BA. Scaling and root planing with and without periodontal flap surgery. J Clin Periodontol 1986; 13:205-210.

(25.) Rabbani GM, Ash MM Jr, Caffesse RG. The effectiveness of scaling and root planing in calculus removal. J Periodontol 1981; 52(3): 119-123.

(26.) Johnson LR, Stoller NH. Rationale for the use of Atridox therapy for managing periodontal patients. Compendium 1999; (20) 19-25.

(27.) Garrett S, Johnson L, Drisko CH, et al. Two multicenter studies evaluating locally delivered doxycycline hydate, placebo control, oral hygiene, and scaling and root planing in the treatment of periodontitis. J Periodontol 1999; 70(5): 490-503.

(28.) Ciancio SG. Local delivery of chlorhexidine. Compendium 1999; 20:427-433

(29.) Fleming TF, Newman MG, Doherty FM, Grossman E, Meckel AH, Bakdash B. Supragingival irrigation with 0.06% chlorhexidine in naturally occurring gingivitis. 1. 6-month clinical observations. J Periodontol 1990; 51:112-117.

(30.) Killoy WJ. Assessing the effectiveness of locally delivered chlorhexidine in the treatment of periodontitis. JADA 1999; 130:567-570.

(31.) Okano M, Nomuar M, Hata S, et al. Anaphylactic symptoms due to chlorhexidine gluconate. Arch Dermatol 1989; 125:50-52

(32.) Soskolne WA, Heasman PA, Stabholz A, et al. Sustained local delivery of chlorhexidine in the treatment of periodontitis: a multicenter study. J Periodontol 1997; 68:32-38.

(33.) Stanley A, Wilson M, Newman HN. The in vitro effects of chlorhexidine on subgingival plaque bacteria. J Clin Periodontol 1989; 16:259-264.

(34.) Jeffcoat MK, Bray KS, Cianco SG, et al. Adjunctive use of a subgingival controlled-release chlorhexidine chip reduces probing depth and improves attachment level compared with scaling and root planing alone. J Periodontol 1998; 69:989-997.

(35.) Jeffcoat MK, Palcanis KG, Weatherford TW, Reese M, Geurs NC, Flashner M. Use of a biodegradable chlorhexidine chip in the treatment of adult periodontitis: clinical and radiographic findings. J Periodontol 2000; 71:256-262.

The authors are with the Dental Corps, U.S. Army Dental Command, serving at Fort Sam Houston, Texas. Pamila Richter, RDH, is Health Promotion Director; LTC Bruce Brehm, DDS, MPH, is Public Health Dental Officer.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy of the U.S. Department of Defense or other departments of the U.S. Government.

COL Lawrence G. Breault, DMD, MS, is the Chief of Periodontics and Periodontal Mentor for the Advanced General Dentistry Program--one Year, U.S. Army Dental Activity, Fort Benning, GA. SGM Stephen E. Spadaro is the Senior Noncommissioned Officer for the U.S. Army Dental Command (DENCOM), Fort Sam Houston, TX, and the 13th District Trustee for the ADAA.

COPYRIGHT 2004 American Dental Assistants Association

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group