* Extranodal Hodgkin disease presenting as a primary localized neoplasm is uncommon, with rare case reports describing primary sites other than lymph nodes. The gastrointestinal tract is the most frequent site of involvement by extranodal Hodgkin disease, typically involving the stomach or small bowel. To date, we have been able to find only one fully documented case of Hodgkin disease of the sigmoid colon confirmed by immunohistochemical studies. We report a case of extranodal Hodgkin disease involving the transverse colon, presenting as inflammatory bowel disease and documented by light microscopic, immunohistochemical, cytogenetic, and molecular studies.

(Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000;124:1824-1827)

Primary extranodal Hodgkin disease (HD) localized to a particular site or an organ is rare. The gastrointestinal (GI) tract is the most frequent site of involvement by localized extranodal HDI with the stomach being the most common site followed by the small bowel, colon, and esophagus? Literature review revealed one fully documented case of primary HD of the sigmoid colon with immunohistochemical analysis.3 We describe an additional case of primary extranodal HD of the transverse colon in a 42-year-old nonimmunocompromised woman.

REPORT OF A CASE

Clinical History

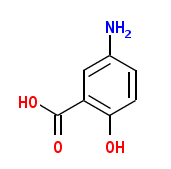

A 42 year-old woman presented in 1985 with intermittent fever, diarrhea, abdominal cramps, and bleeding from the rectum. Colonoscopy performed in 1989 revealed skip lesions in the rectosigmoid area and an inflamed lesion at 80 cm. A biopsy specimen of the inflamed area showed nonspecific ulcer and granulation tissue. The clinical, endoscopic, and pathologic findings were interpreted as consistent with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) of the Crohn type. Initial treatment was sulfasalazine and later Asacol (5-aminosalicylic acid; 800 mg three times a day). However, the patient continued to be symptomatic, with frequent temperature spikes and night sweats. An endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in 1991 showed slight irregularity of the intrahepatic bile ductules and was thought to represent an early phase of primary sclerosing cholangitis. The patient took aspirin frequently for fever and received regular iron and folic acid supplements for persistent anemia. Her hemoglobin level was 95 g/L (range, 140-180 g/L). Her constitutional symptoms never completely abated, and she exhibited no signs or symptoms of perforation or obstruction.

In early 1999, the patient noted increased bleeding from the rectum, and she had a hemoglobin level of 69 g/L (range, 140180 g/L). Colonoscopy showed a few tiny ulcers at 15 cm and a large annular, multilobulated, necrotic-appearing mass at approximately 65 cm. Computed tomographic (CT) scan of the abdomen revealed a marked circumferential thickening of the transverse colon with surrounding mesenteric infiltrate (Figure 1). A biopsy specimen of the mass was interpreted as a high-grade malignant neoplasm. The patient's preoperative laboratory values were remarkable for hemoglobin (109 g/L; range, 140-180 g/L), hematocrit (0.20; range, 0.40-0.50), and mean corpuscular volume (74 fL; range, 82-99 fL). The patient underwent an extended right hemicolectomy, including the transverse colon, to the level of the splenic flexure. Her postoperative course was uneventful, and she was discharged on postoperative day 4 in good condition. A second CT scan of the abdomen showed no significant hepatosplenomegaly or abdominal lymphadenopathy. Results of a CT scan of the chest were unremarkable.

Ten months after surgery, the patient was essentially relieved of fever and night sweats and started to regain weight, with marked improvement in appetite. The results of bone marrow studies, including aspiration and biopsy, were normal. A bone scan and gallium scan demonstrated no suspicious foci. Because of her symptoms of fever and night sweats and the histologic findings demonstrating HD, lymphocyte-depleted type, the patient received cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine (Oncovin), and prednisone chemotherapy for the next 6 months without any serious adverse effects. Follow-up 2 months after chemotherapy revealed no residual disease.

Gross Pathologic Findings

The resected specimen consisted of a short segment of terminal ileum, cecum with appendix, and an 80-cm length of colon. An approximately 14-cm length of the transverse colon was involved by a multinodular mass, with marked narrowing of the lumen (Figure 2). The mucosa in this area was ulcerated and dark brown. The mass infiltrated the entire thickness of the colon wall and focally extended into pericolic fat. The cut surface of the tumor was fibrotic, tan-pink, and homogenous in appearance. There were no areas of hemorrhage or necrosis. The remainder of the terminal ileum, cecum, appendix, and uninvolved colon were unremarkable. The mucosae showed no ulcers, and the muscularis was not thickened. No fat wrapping was identified. A few small pericolic lymph nodes were identified and appeared within normal limits.

Light Microscopic Findings

In the area of the mass, the entire mucosa, submucosa, and muscularis were diffusely infiltrated by a mixed infiltrate composed of sparse, small, mature lymphocytes, eosinophils, and neoplastic cells in a reactive fibrotic stroma (Figure 3, a). The neoplastic cells were uninucleated, binucleated, or multinucleated medium-to-large polygonal cells in either aggregates or confluent sheets. These cells had moderate-to-abundant slightly eosinophilic cytoplasm. The nuclei were large and vesicular with prominent nucleoli. Multilobated and folded nuclei were commonly seen. Binucleate cells with prominent eosinophilic nucleoli consistent with Reed-Sternberg cells were frequently noted (Figure 3, b). The light microscopic features were interpreted as consistent with HD, lymphocyte-depleted type. The colon epithelium overlying the tumor was completely ulcerated and showed inflamed granulation tissue. The remainder of the mucosa of the colon, ileum, and appendix showed no histologic evidence of Crohn disease. Pericolic lymph nodes showed reactive changes.

Immunohistochemical Observations

The large neoplastic cells demonstrated strong positive immunoreactivity for vimentin, CD15 (Leu-Ml) (Figure 4, a), and CD30 (Ber-142) (Figure 4, b), with the latter 2 antibodies showing strong membranous staining with a characteristic paranuclear dot pattern. Many of the neoplastic cells expressed Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein. In situ hybridization for EpsteinBarr virus was positive in these cells as well. The large neoplastic cells were nonimmunoreactive for antibodies directed against CD45, CD20 (L26), CD79a, CD3, CD43, CD45RO (UCHL-1), epithelial membrane antigen, CD68, CDla, cytokeratins, muscle actins, desmin, myoglobin, 5100 protein, and HMB-45. No evidence of K or X light chain restriction was seen. T-cell markers (CD3 and CD45RO) did, however, highlight the small, mature background lymphocytes.

Cytogenetic and Molecular Studies

Chromosome analysis revealed a normal 46XX karyotype in 19 of 20 cells analyzed. The remaining cell showed random loss of chromosomes 20 and 21. Genotypic investigation by Southern blot analysis showed germline configuration of the T-cell receptor beta and gamma genes and immunoglobulin heavy and light chain genes.

COMMENT

Extranodal HD presenting as a localized process with no lymph node involvement is rare, with an estimated incidence of less than 1% of all patients with HD.1 The liver and lung are common extranodal sites involved by nodal HD,4,5 whereas the GI tract is noted as the most frequent site for primary extranodal HD.1 The stomach and small bowel are more frequently involved than the colon or esophagus.2,6 Other reported sites of primary extranodal HD include the lung, thyroid, skin, central nervous system, and genitourinary tract.7

Hodgkin disease primarily involving the colon without nodal disease has been described in the literature mostly as single case reports and occasionally as part of larger series.8-18 A recent review reported one case of primary HD of the sigmoid colon and found an additional 26 cases of primary HD of the colon.3 A recent abstract reported 4 cases of primary HD of the colon that were multifocal and associated with immunosuppression from treatment for IBD and Epstein-Barr virus.13 The colonic sites involved by primary HD in order of frequency are the rectum, cecum, sigmoid colon, and splenic and hepatic flexures.3 There are no specific signs or symptoms associated with the disease. However, most patients presented with intermittent abdominal cramps, anorexia, weight loss, altered bowel habits, and bleeding from the rectum, all features commonly associated with IBD. With the exception of 1 previous case report and 4 recent cases reported as an abstract,3,13 none of the other reports have used immunohistochemical studies to substantiate the light microscopic diagnosis. The lack of confirmatory immunohistochemical data leaves open the possibility that some of the previously reported cases of primary GI HD may represent non-HD lymphoma rather than HD.19,20

A diagnosis of primary extranodal HD of the colon requires exclusion of nodal HD and other benign and malignant conditions. Appropriate investigations (CT scan of the chest and abdomen) to rule out mediastinal and abdominal lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly should be performed along with a careful clinical search for enlarged superficial lymph nodes. Bone marrow studies and complete blood cell counts are important. These studies are necessary to stage the patient's disease and also to document the absence of HD elsewhere. In addition, with the increase in lymphoid malignant neoplasms, including HD, in immunocompromised hosts, careful evaluation for causes of immunosuppression is warranted.

In view of the distinct rarity of GI HD, the microscopic diagnosis should be based on stringent histologic and immunologic criteria.3,11,21 Histologically, the neoplasm should have characteristic Reed-Sternberg cells or its variants in a background consistent with one of the subtypes of HD. Immunophenotypic markers should confirm the light microscopic features. Immunophenotypic analyses have shown the Reed-Sternberg cells in classic HD to express vimentin, CD15, and CD30 in most cases, the latter 2 antibodies showing a membranous staining combined with paranuclear decoration.22 The Reed-Sternberg cells are typically negative for CD45. Although cytogenetics and molecular analyses have no specific diagnostic implications in HD, they may be helpful in excluding CD30positive large cell anaplastic lymphoma and other large cell non-HD lymphomas.

The patient we describe in this case report was thought to have IBD and was treated as such. However, the patient continued to have symptoms, on and off, related to a slowly growing, constricting lesion in her transverse colon. The review of the biopsy specimen from 1991 in fact showed ulceration and chronic inflammation with lymphocytes and plasma cells. The immunohistochemical studies were noncontributory. It is uncertain whether the patient actually had IBD despite endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and biopsies. It was only recently, in 1999, that the patient was found to have a large constricting mass in the transverse colon and the diagnosis of primary HD of the transverse colon was made after colectomy.

Extranodal HD localized to the colon with negative lymph node is staged as IE.21 There is no uniformly accepted treatment for extranodal localized HD. In most of the previously reported cases, the patients did well with surgical resection alone.11 The usefulness of adjuvant chemotherapy is not yet known. Current thinking suggests that it may prevent relapse or local recurrence, although larger studies are needed for a definitive standardized treatment protocol.

In conclusion, an unusual case of extranodal HD localized to the transverse colon and presenting with signs and symptoms of IBD is described. Because of its rare occurrence in the GI tract, extensive investigations should be conducted to exclude primary nodal disease. Strict histopathologic and immunophenotypic criteria must be used for the diagnosis of HD. The prognosis of HD localized to one particular site appears good with surgical resection. In addition, HD should be included in the differential diagnosis in patients with atypical presentation for IBD.

We thank Paulette E. Pierson, PhD, for her insight and help in preparing the manuscript.

References

1. Wood NL, Coltman CA Jr. Localized primary extranodal Hodgkin's disease. Ann Intern Med. 1973;78:113-118.

2. Naqvi MS, Burrows L, Kark AE. Lymphoma of the gastrointestinal tract: prognostic guides based on 162 cases. Ann Surg. 1969;170:221-231.

3, Thomas DB, Huston BM, Lamm KR, Maia DM. Primary Hodgkin's disease of the sigmoid colon: a case report and review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1997;121:528-532.

4. Colby TV, Hoppe RT, Warnke RA. Hodgkin's disease at autopsy: 1972-1977. Cancer. 1981;47:1852-1862.

5. Grogan TM, Berard CV, Steinhorn SC. Changing patterns of Hodgkin's disease at autopsy: a 25-year experience at the National Cancer Institute, 19531978. Cancer Treat Rep. 1982;66:653-665.

6. Portmann UV, Dunne EF, Hazard JD. Manifestations of Hodgkin's disease of the gastrointestinal tract. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1954;72:772787.

7. Langenhuijsen MMAC, Eibergen R, Halie MR. Primary extranodal Hodgkin's disease: report of five cases and survey of the literature. Neth J Med. 1976;19: 224-233.

8. Allen AW, Donaldson G, Sniffen RC, Goodale F Jr. Primary malignant lymphoma of the gastro-intestinal tract. Ann Surg. 1954;140:428-437.

9. Centurioni R, Rupoli S, Marchegiani G, Leoni P. Primary Hodgkin's lymphoma of the sigmoid colon [letter]. Haematologica. 1986;71:351-352.

10. Crowley KS, Don G, Gibson GE, Juttner CA, Miliauskas JR. Primary gas

trointestinal tract lymphoma: a clinicopathological study of 28 cases. Aust N Zi Med. 1982;12:135-142.

11. Dawson IMP, Comes JS, Morson BC. Primary malignant lymphoid tumors of the intestinal tract: report of 37 cases with a study of factors influencing prognosis. Br J Surg. 1961;48:80-94.

12. Groebli Y, Deltour D, Jacot-des-Combes E, Rohner A. An unusual cause of sigmoid tumor: primary Hodgkin's disease. Acta Chir Scand. 1988;154:67-69. 13. Kumar S, Kingma DW, Quintanilla-Martinez L, et al. EBV + primary gas

trointestinal Hodgkin's disease: association with inflammatory bowel disease and immunosuppression [abstract]. Mod PathoL 1999;12:141 A.

14. McNatt M. Primary Hodgkin's granuloma of the sigmoid flexure: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 1968;11:55-60.

15. Shapiro HA. Primary Hodgkin's disease of the rectum. Arch Intern Med.

1961;107:170-173.

16. Warren KW, Littlefield JB. Malignant lymphomas of the gastrointestinal

tract. Surg Clin North Am. 1955;35:735-746.

17. Warren S, Lulenski CR. Primary, solitary lymphoid tumors of the gastrointestinal tract. Ann Surg. 1942;115:1-12.

18. Wychulis AR, Beahrs OH, Woolner LB. Malignant lymphoma of the colon: a study of 69 cases. Arch Surg. 1966;93:215-225.

19. Loehr WJ, Mujahed Z, Zahn FD, Gray GF, Thorbjarnarson B. Primary lymphoma of the gastrointestinal tract: a review of 100 cases. Ann Surg. 1969;170: 232-238.

20. Shepherd NA, Hall PA, Coates PJ, Levison DA. Primary malignant lymphoma of the colon and rectum: a histologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 45 cases with clinicopathological correlation. Histopathology. 1988;12:235252.

21. Devaney K, Jaffe ES. The surgical pathology of gastrointestinal Hodgkin's disease. Am J Clin Pathol. 1991;95:794-801.

22. Rudiger T, Ott G, Om MM, Muller-Deubert SM, Muller-Hermelink HK. Differential diagnosis between classic Hodgkin's lymphoma, T-cell-rich B-cell lymphoma, and paragranuloma by paraffin immunohistochemistry. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:1184-1191.

Accepted for publication May 9, 2000.

From the Departments of Pathology (Drs Vadmal, DeYoung, Frankel, and Marsh) and Surgery (Dr LaValle), University Hospital and James Cancer and Research Institute, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio.

Reprints: Manjunath S. Vadmal, MD, Department of Clinical Pathology and Medicine, University of Southern California, Keck School of Medicine, 2011 Zonal Avenue, HMR-209, Los Angeles, CA 90033.

Copyright College of American Pathologists Dec 2000

Provided by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights Reserved