Study objectives: Despite the success of specialist cough clinics, there is increasing recognition of a subgroup of chronic coughers in whom a diagnosis cannot be made even after thorough, systematic investigation. We call this condition chronic idiopathic cough (CIC). The aim of this study is to compare the clinical characteristics of CIC patients with those of coughers in whom a diagnosis has been established (non-CIC) to see if there is a recognizable clinical pattern that distinguishes CIC from non-CIC.

Design: Retrospective analysis of the medical records of chronic cough patients.

Setting: The Royal Brompton Hospital Chronic Cough Clinic, London.

Patients: One hundred patients with chronic cough referred to the Royal Brompton Hospital Cough Clinic between October 2000 and February 2004.

Results: Seventy-one percent of all patients were female. Median age was 57 years (range, 19 to 81 years), with a median duration of symptoms of 48 months (range, 2 to 384 months). The primary diagnoses were CIC (42%), postnasal drip syndromes (22%), gastroesophageal reflux disease (16%), asthma (7%), and others (13%). In CIC patients, the median age at referral, age at onset of cough, and proportion of females did not differ significantly from non-CIC patients. CIC patients had a longer median duration of cough (72 months vs 24 months, p = 0.002), were more likely to report an upper respiratory tract infection (URTI) as the initial trigger of their cough (48% vs 24%, p = 0.0014), and had a significantly lower cough threshold in response to capsaicin (log concentration of capsaicin required to induce five or more coughs, -0.009 vs 0.592, p = 0.032) than non-CIC patients.

Conclusions: Patients with CIC commonly describe a URTI that initiates their cough, which then lasts for many years, and they demonstrate an exquisitely sensitive cough reflex. We believe that CIC may be a distinct clinical entity with an as-yet unidentified underlying pathology.

Key words: chronic cough; etiology; idiopathic cough

Abbreviations: C5 = concentration of capsaicin required to induce five coughs; CIC = chronic idiopathic cough; GERD = gastroesophageal reflux disease; URTI = upper respiratory tract infection

**********

Chronic cough is a common yet highly troublesome complaint that is frequently referred to respiratory specialists. A cough is arbitrarily defined as being chronic when it has lasted for > 8 weeks, whereas acute coughing tends to last < 3 weeks. Coughs lasting from 3 to 8 weeks are sometimes referred to as subacute. (1) Chronic cough has traditionally been seen as a symptom, the cause of which is often difficult to diagnose and treat. However, with the introduction of specialist cough centers utilizing systematic protocols for investigation and treatment, the underlying diagnoses have been identified in anywhere from 80 to 100% of cases with equally impressive treatment outcomes. (2-8) In all of these centers, the three most common causes of cough have been asthma, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), and postnasal drip syndromes. (9) Our experience at The Royal Brompton Hospital Cough Clinic in London has been rather different. The majority (73%) of patients referred to The Royal Brompton Cough Clinic have already been seen and investigated by a respiratory specialist. We are therefore faced with a highly selected population of chronic cough patients whose diagnoses have already eluded specialist investigation. With such extensive exposure to "idiopathic" coughers, we are in the unique position of being able to characterize the syndrome of chronic idiopathic cough (CIC).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The medical records of all patients referred to The Royal Brompton Cough Clinic between October 2000 and February 2004 were collected and reviewed. All patients had a cough of at least 8 weeks' duration. Referrals were made by primary care physicians, respiratory specialists, and other hospital specialists. The following information was collected from the medical records: name; date of birth; sex; source of referral; previous investigation by a respiratory specialist; age at onset of cough; duration of symptoms; preceding upper respiratory tract infection (URTI); smoking habits; results of capsaicin challenges (concentration of capsaicin required to induce five coughs [C5]), histamine challenges, and 24-h esophageal pH monitoring; primary, secondary and tertiary diagnoses; and response to treatment.

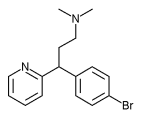

Investigation and treatment of these patients were based on protocols previously described by Irwin et al. (10) Those patients for whom systematic investigation did not yield a specific diagnosis and in whom trials of specific therapy did not improve their symptoms were given a diagnosis of CIC. The specific treatments that were administered and the minimum duration of treatment given before a diagnosis of CIC was made were as follows: Suspected postnasal drip syndromes were treated with a combination of sedating antihistamine (chlorpheniramine or brompheniramine) and a decongestant (pseudoephedrine) followed by a nasal steroid. Treatment duration was a minimum of 2 months. Suspected GERD was treated with high doses of proton-pump inhibitors followed by the addition of alginates and finally the addition of a prokinetic agent (metoclopramide). Treatment duration was a minimum of 6 months. Suspected asthma was treated in the first instance with a regular inhaled steroid along with a short-acting [[beta].sub.2]-agonist as required. If this proved inadequate, treatment was stepped up according to the British Thoracic Society guideline on the treatment of asthma. (11)

The clinical features of patients with CIC were compared with those of patients with other identifiable causes of cough to see if there were any characteristics of CIC patients that distinguished them from other coughers. Statistical analysis of quantitative data (age at referral, age at onset of cough, duration of cough, log C5) was performed using the Mann-Whitney U test. Dichotomous data (gender, previous URTI) were analyzed with the [chi square] test. All analyses were performed using statistical software (GraphPad Prism; GraphPad Software; San Diego, CA).

RESULTS

Information was gathered from a total of 100 consecutive new patient referrals between October 2000 and February 2004. Seventy-three of these had been previously seen and investigated for their cough by a respiratory specialist. Seventy-one were female. The median age of the patients at referral was 57 years (range, 19 to 81 years). The median age at the onset of cough was 48.5 years (range, 19 to 76 years). The median duration of symptoms was 48 months (range, 2 to 384 months). Only 3 patients were current smokers, and 45 were ex-smokers, with a mean number of pack-years of 19.3.

A cause for the cough was identified in 58 patients. Fifty of these patients responded successfully to treatment. The other eight patients showed some response to treatment, but the cough still persisted. A cause was not found in 42 patients. These patients were therefore given a diagnosis of CIC. This group consisted of 25 patients in whom all investigation findings were negative and 17 patients in whom investigations suggested a potential cause but specific treatment yielded no sustained benefit. The frequencies of all the primary causes are summarized in Tables 1, 2.

The characteristics of the 42 patients with CIC were compared with those of 58 patients in whom another diagnosis had been made. For the purposes of this analysis, this latter group was described as non-CIC. These results are summarized in Table 3 and Figures 1-3. The CIC patients had a median age of 57 years (range, 32 to 81 years). The median age of onset of cough in this group was 46.5 years (range, 27 to 71 years), and 76% were female. The respective values for the non-CIC patients were 58 years (range, 19 to 78 years), 49.5 years (range, 19 to 76 years), and 69%. None of these characteristics were significantly different between the two groups. The median duration of cough in the CIC was group was 72 months (range, 8 to 324 months) compared with 24 months (range, 2 to 384 months) in the non-CIC group (p = 0.002). Twenty CIC patients (48%) described the onset of their cough as being triggered by a URTI, compared with 14 patients in the non-CIC group (24%), a difference that was statistically significant (p = 0.014). Capsaicin challenge results were available from 25 CIC patients and 20 non-CIC patients. The CIC group demonstrated an increased cough sensitivity, with a median log C5 of -0.009, compared with 0.592 in the non-CIC group (p = 0.032).

[FIGURES 1-3 OMITTED]

DISCUSSION

Within the large population of patients with chronic cough, there is a very small subgroup in whom thorough investigation yields no diagnosis. Given that most of the patients referred to The Royal Brompton Cough Clinic have already been unsuccessfully investigated by a respiratory physician, this subgroup constitutes a large proportion of the patients that we see. We have described this group as having CIC. Forty-two percent of our cough patients have CIC, and it is the most common diagnosis in our specialist clinic. This is in stark contrast to the results of other reported cough studies. (2-8) Our CIC group is likely to consist of a variety of as-yet unidentified pathologies, but an identifiable pattern in the characteristics of these patients has emerged. The classic story is one of a URTI that initially triggers the cough. The infection subsides, but the cough persists. In some of these patients, the cough subsides within a few months. We diagnose this as a postviral cough. In others, the cough persists for years. These patients describe multiple visits to primary care physicians, respiratory specialists, and ear, nose, and throat surgeons. These patients have usually tried many courses of empiric therapy, all of which are ineffective. They clearly describe symptoms of exquisitely sensitive cough reflexes. Crumbly foods such as bread and biscuits along with strong smells from perfume and cooking trigger their cough. Sometimes laughing or any increase in the rate of breathing is sufficient to cause coughing. This heightened cough sensitivity is objectively demonstrated by the increased capsaicin sensitivity when compared to other diagnosed coughers.

The mechanisms of CIC are currently unknown, although the markedly increased sensitivity to capsaicin challenge indicates that the cough reflex is greatly sensitized. This may be similar to other sensory hyperalgesias, where there is a long-standing reduction in sensory nerve threshold to stimulation. (12,13) This may follow sensory nerve injury, and it is possible that sensory nerves may be damaged during some URTIs. To conclude, we still believe that in the majority of unselected chronic coughers, systematic investigation will yield a specific diagnosis that can be successfully treated. However, in many of the undiagnosed patients, there is a characteristic pattern of URTI, a long history of cough, and heightened cough sensitivity. The association of CIC with an initial triggering URTI may give a clue to the etiology of this condition. CIC may be a variation of "postviral cough" but with an extremely prolonged clinical course. A minor respiratory viral infection in susceptible individuals may lead to a persistent inflammatory response in the upper airways, leading to heightened cough sensitivity and a persistently troublesome cough long after the initial infection has been cleared. Given the socially debilitating nature of CIC and its heavy impact on quality of life, such patients deserve more research into the true nature of their underlying pathology and a drive for a truly effective antitussive treatment.

* From Airway Disease Section, National Heart & Lung Institute, Imperial College, London, UK.

REFERENCES

(1) Irwin RS, Madison JM. The diagnosis and treatment of cough. N Engl J Med 2000; 343:1715-1721

(2) Poe RH, Harder RV, Israel RH, et al. Chronic persistent cough: experience in diagnosis and outcome using an anatomic diagnostic protocol. Chest 1989; 95:723-728

(3) Irwin RS, Curley FJ, French CL. Chronic cough: the spectrum and frequency of causes, key components of the diagnostic evaluation, and outcome of specific therapy. Am Rev Respir Dis 1990; 141:640-647

(4) O'Connell F, Thomas VE, Pride NB, et al. Capsaicin cough sensitivity decreases with successful treatment of chronic cough. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1994; 150:374-380

(5) McGarvey LP, Heaney LG, Lawson JT, et al. Evaluation and outcome of patients with chronic non-productive cough using a comprehensive diagnostic protocol. Thorax 1998; 53:738-743

(6) Palombini BC, Villanova CA, Aranjo E, et al. A pathogenic triad in chronic cough: asthma, postnasal drip syndrome, and gastroesophageal reflux disease. Chest 1999; 116:279-284

(7) Brightling CE, Ward R, Goh KL, et al. Eosinophilic bronchitis is an important cause of chronic cough. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999; 160:406-410

(8) Irwin RS, Corrao WM, Pratter MR. Chronic persistent cough in the adult: the spectrum and frequency of causes and successful outcome of specific therapy. Am Rev Respir Dis 1981; 123:413-417

(9) Morice AH. Epidemiology of cough. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 2002; 15:253-259

(10) Irwin RS, Boulet LP, Cloutier MM, et al. Managing cough as a defense mechanism and as a symptom: a consensus panel report of the American College of Chest Physicians. Chest 1998; 114(Suppl):133S-181S

(11) British Thoracic Society, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). British guideline on the management of asthma. Thorax 2003; 58(supp1 1):i1-i94

(12) Carr MJ, Undem BJ. Pharmacology of vagal afferent nerve activity in guinea pig airways. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 2003; 16:45-52

(13) Morice AH, Geppetti P. Cough 5: the type 1 vanilloid receptor; a sensory receptor for cough. Thorax 2004; 59:257-258

Manuscript received September 24, 2004; revision accepted October 26, 2004.

Reproduction of this article is prohibited without written permission from the American College of Chest Physicians (www.chestjournal. org/misc/reprints.shtml).

Correspondence to: Rubaiyat A. Haque, MBBS, Airways Disease Section, National Heart & Lung Institute, Imperial College, Dovehouse St, London, SW3 6LY, UK; e-mail: r.haque@imperial. ac.uk

COPYRIGHT 2005 American College of Chest Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2005 Gale Group