Let's find out whether cannabis has therapeutic value

EDITOR--In discussions of the use of cannabis one of the biggest problems over the past few years has been the difficulty in separating the debate on the recreational use from that on the therapeutic use. The article by Strung et al also mixes the two issues.[1]

In all my years of working in pain relief I cannot remember the equivalent mix-up taking place over cocaine, morphine, heroin, etc. Although some matters occasionally overlap, the two main elements of the cannabis debate must remain in separate arenas. Only then can we educate politicians and the public about the facts and the real issues.

Meanwhile, let's get on and find out whether cannabis has significant and valuable therapeutic potential. This agent has been used medicinally for 5000 years and we still don't know whether it is therapeutically effective.

William Notcutt consultant anaesthetist James Paget Hospital, Great Yarmouth NR31 6LA willy@tucton.demon.co.uk

[1] Strang J, Witton J, Hall W. Improving the quality of the cannabis debate: defining the different domains. BMJ 2000;320:108-10. (8 January.)

Consider public welfare, not just public health

EDITOR--Strang et al raise a number of salient issues in the debate over whether cannabis should be legalised.[1] However, the eight "domains of the cannabis debate" identified are centred exclusively on a public health conception of the relevant policy issues. Although this is understandable given the audience that the authors are addressing, they fail to consider more fundamental issues of what the public policy objectives should be when considering the recreational use of cannabis.

Their discussion reflects the fact that the medical profession has a natural tendency to judge the public regulation and legal control of activities according to their impact on the health of the public. Thus, anything shown to be harmful to health is seen as inherently bad, while activities that promote health are seen as something to be encouraged by public institutions.

An alternative vision of the objective of public intervention and legislative structures is that they should exist to protect and improve public welfare as distinct from public health. Individual welfare is clearly affected by health but it also encompasses a broader class of personal benefits that people enjoy when freely undertaking specific activities (including using cannabis), even in cases in which they are knowingly exposing themselves to possible health risks.

This "welfarist" angle should not be confused with the libertarian line, which would espouse the removal of legal barriers that prevent people having the freedom to do as they wish. In the welfarist paradigm public regulation and control will always be required if the use of cannabis affects the welfare (including the health) of parties who are outside the decision to use. Public intervention is also needed to ensure that users are informed of any risks associated with use, even if this means telling people that at present the risks are largely unknown.

If it is accepted that health is only one aspect of individual welfare and that it is the responsibility of government to promote individual welfare even if in certain instances this means compromising health, then a public health driven debate will never offer satisfactory guidance on the desirability of the legal status quo of cannabis use.

Andrew Healey research officer Department of Social Policy, London School of Economics and Political Science, London WC2A 2AE

A.T. Healey@lse.ac.uk

[1] Strang J, Witton J, Hall W. Improving the quality of the cannabis debate: defining the different domains. BMJ 2000;320:108-10. (8 January.)

Social context should be added to domains being considered

EDITOR--Strang et al argue that the cannabis debate has been oversimplified into polarised positions that consider cannabis to be either generally harmless and potentially therapeutic or harmful to health and consequently deserving of prohibition.[1] To improve the quality of debate the authors usefully identify eight domains within which the health effects of cannabis should be examined. However, these domains represent only a narrow biological view of this difficult issue and focus almost exclusively on examining potentially negative effects. Further overarching domains, in particular of social context, need to be added to the debate.

Social opportunity costs arise as a result of criminalising cannabis users. These include their exclusion from school, university, and employment; incarceration; and blighting of their lives and careers as consequences of their becoming involved with criminal subcultures. Furthermore, cannabis use should be considered against the health consequences of alternative drugs, such as alcohol, which compete within a similar social niche. Current ethics do not provide an even handed assessment of alcohol--the drug of choice of large numbers of older people--and cannabis--the drug of choice of many younger people. Testing alcohol against Strung et al's domains is an informative exercise.

At the other end of the drug spectrum, cannabis legislation ties up disproportionate amounts of police and other judicial time. In 1998, of the 2240 police incidents directly involving drugs in Merseyside, 70.8% related to cannabis while heroin incidents accounted for only 6.3%.[2] Consequently, the cost of current cannabis legislation also includes the diversion of judicial efforts away from drugs that have enormous repercussions for health.

Perhaps we can now begin to have an objective, evidence based, and inclusive discussion of the whole topic of alcohol and drug abuse, which includes tobacco, and which takes a social administration perspective in looking at the costs and benefits of social policy in full rather than being narrowly concerned with selective biological aspects.

John R Ashton regional director of public health NHS Executive North West, Warrington WA3 7QN

Mark A Bellis head of public health Public Health Sector, Liverpool John Moores University, Liverpool L3 2AB m.a.bellis@livjm.ac.uk

[1] Strang J, Witton J, Hall W. Improving the quality of the cannabis debate: defining the different domains. BMJ 2000;320:108-10. (8 January.)

[2] Hardi L, Bellis MA. Merseyside interagency drug misuse database: a unified approach to drug misuse data. Liverpool: Molyneux, 1999.

The effects of cannabis on driving are difficult to evaluate

EDITOR--In their article on the cannabis debate, Strang et al raise the issue of cannabis and its effects on driving, suggesting that "a clearer understanding will be required of the extent to which a particular concentration of the drug (or its metabolites) can reliably be taken as evidence that an individual's driving ability was consequently impaired."[1] A review of the literature, however, suggests that defining an acceptable level of cannabis consumption for driving is unlikely to be possible for several reasons.

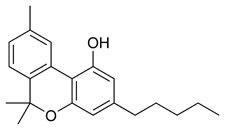

Firstly, there is a poor correlation between plasma concentrations of trans-[Delta]-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) (the constituent of cannabis responsible for the production of most of the psychoactive response) after smoking and subjective, self reported psychological effects; plasma concentrations of THC decline long before peak effects are felt.[2] Secondly, the relation between psychological testing and performance in experiments of real driving is complex because the two modalities of testing are different. Impairment in driving has been shown experimentally with acute intoxication by cannabis[3]; however, attempts to correlate driving performance with concentrations of THC will be severely affected by the observed time lag between THC concentrations and peak effects.

The issue is further complicated in people who use cannabis heavily for prolonged periods. This group has been shown to develop tolerance to the somatic and psychological effects of THC; this tolerance cannot be correlated with any drop in concentration below that of users who are not tolerant.[4] Chronic heavy users of cannabis do, however, show subtle impairment in memory, organisation, and attention, and the effect becomes more pronounced the longer the duration of use.[5] Whether these effects diminish the ability to drive is not clear, but since they are unrelated to acute intoxication, it is unlikely that it will ever be possible to correlate them with concentrations of THC. Furthermore, it is not clear whether these abnormalities are reversible with prolonged abstinence.

The pursuit of a definition of a "safe" amount of cannabis that can be consumed and still allow for driving is unlikely to be successful.

Sarah Levy registrar in toxicology

Alison Jones consultant toxicologist National Poisons Information Service (London), Medical Toxicology Unit, London SE 14 5ER sarah.levy@gstt.sthames.nhs.uk

[1] Strang J, Witton J, Hall W. Improving the quality of the cannabis debate: defining the different domains. BMJ 2000;320:108-10. (8 January.)

[2] Perez-Reyes M, DiGuiseppi S, Davis KH, Schindler VH, Cook CE. Comparison of effects of marijuana cigarettes of three different potencies. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1982;131: 617-24.

[3] Smiley A. Marijuana: on road and driving simulator studies. In: Kalant H, Corrigal W, Hall W, Smart R, eds. The health effects of cannabis. Toronto: Addiction Research Foundation, 1998.

[4] Hunt CA, Jones RT. Tolerance and disposition of tetra hydro cannabinol in man. J Pharmacol Exper Ther 1980;215:35-44.

[5] Solowij N. Cannabis and cognitive functioning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

COPYRIGHT 2000 British Medical Association

COPYRIGHT 2000 Gale Group