Renovascular hypertension refers to hypertension caused by renal hypoperfusion, which is usually the result of renal artery stenosis. The stenosis may be unilateral or bilateral and may involve one or more branches of the renal artery. Renal artery stenosis by itself does not necessarily imply renovascular hypertension; in some cases, the stenosis is not physiologically significant but is simply an incidental finding in a patient with essential hypertension. Therefore, the angiographic demonstration of stenosis in a hypertensive patient does not prove that the stenosis caused the hypertension.

The prevalence of renovascular hypertension varies with the nature of the hypertensive population. In the primary care setting, the prevalence of renovascular hypertension is less than 1 percent.[1] However, in patients with suggestive clinical features, the prevalence of renovascular hypertension is higher. In a study of patients with accelerated or malignant hypertension, 4 percent of blacks and 32 percent of whites had renovascular hypertension.[2] It also occurs more frequently in hypertensive patients with evidence of atherosclerosis in the peripheral, carotid and coronary vasculature, and in patients with rapidly progressing renal insufficiency, particularly after therapy with an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor.[3,4]

The Working Group on Renovascular Hypertensions lists clinical findings that suggest an increased likelihood of renal artery stenosis (Table 1). Renovascular hypertension seems to be less common in blacks and diabetic patients,[6,7] even though they have a higher prevalence of renal artery stenosis. Approximately two thirds of all renal artery stenoses are atherosclerotic; most of the remaining stenoses are the result of fibromuscular dysplasia (usually occurring in young women). Renovascular hypertension has also been recognized in neonates, children and pregnant women.[8]

TABLE 1 Clinical Findings That Suggest Renovascular Hypertension

ACE = angiotensin-converting enzyme.

Adapted from Working Group on Renovascular Hypertension. Detection, evaluation, and treatment of renovascular hypertension: final report. Arch Intern Med 1987;147:820-9.

The physiologic basis of renovascular hypertension is renal ischemia from hypoperfusion that, in turn, activates the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. The elevation of angiotensin leads to high peripheral resistance, and the increased aldosterone level leads to volume retention; together, these result in hypertension. High angiotensin levels also constrict the glomerular efferent arteries and, thus, preserve glomerular filtration.

Early diagnosis and treatment of renovascular hypertension may result in a cure of the hypertension or a decrease in the number of medications or the dosage level required for blood pressure control. Early treatment may also preserve renal function. As mentioned earlier, not all renal artery stenoses cause renovascular hypertension. Therefore, testing for renovascular hypertensive disease calls for delineating not only the presence of renal artery stenosis but also its physiologic significance. The gold standard for viewing the renal vasculature is renal arteriography.[9] The risks associated with this procedure include arteriotomy, atheroembolism and nephrotoxicity resulting from the use of contrast agents.[10]

A number of less invasive diagnostic alternatives may be more appropriate in cases where the clinical suspicion of renovascular hypertension is not high enough to warrant the risk and expense of renal arteriography.

Captopril-Augmented Renal Scintigraphy

Captopril-augmented renal scintigraphy, a procedure easily accomplished on an outpatient basis, is now widely used for the detection of renal artery stenosis.[11]

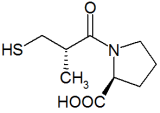

In the procedure, a renally excreted radionuclide is given after administration of an ACE inhibitor, most usually captopril (Capoten). Captopril-augmented renal scintigraphy takes advantage of the temporary changes in renal function that are induced by captopril (Figure 1, A and B).

[Figures 1 ILLUSTRATION OMITTED]

Renal artery stenosis leads to hypoperfusion of the affected kidney, causing increased intrarenal secretion of angiotensin I, which is then converted to angiotensin II and causes constriction of glomerular efferent arterioles. This vasoconstriction preserves intraglomerular pressure and, consequently, glomerular filtration. When the conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II is blocked by an ACE inhibitor, the efferent vasoconstriction is relieved and, consequently, intraglomerular pressure falls abruptly, leading to decreased glomerular filtration. Renal scintigraphy after ACE inhibition demonstrates a decrease in glomerular filtration in the presence of a physiologically significant renal artery stenosis.

Renal scintigraphy may be performed using radiolabeled agents that are excreted primarily by glomerular filtration (e.g., technetium-99 diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid [[sup.99]Tc-DTPA]) or tubular secretion (orthoiodohippurate-131 or 99Tc-mercaptoacetyltriglycine [[sup.99m]Tc-[Mag.sub.3]]).

Renal function in an ischemic kidney is abruptly reduced after one dose of an ACE inhibitor. With [sup.99]Tc-DTPA, the post-captopril study demonstrates a marked reduction in uptake of DTPA on the affected side. Tubular agents like [sup.99m]Tc-[Mag.sub.3], on the other hand, demonstate progressive accumulation in the affected kidney during the course of the study. Reduced glomerular filtration rate causes slow transit of tubular fluid through the tubules, which leads to retention of radiotracing agent in the tubules.

In the presence of renal artery stenosis, asymmetry of radionuclide uptake, excretion, or both, may occur. Typically, less than 40 percent of the total radionuclide uptake is in the affected kidney, and more than 60 percent of the total renal uptake is on the contralateral side.[12-14] Radionuclide excretion is usually expressed as time to peak activity, if a peak can be identified,[13] and as a percentage of peak activity remaining in each renal cortex 15 to 20 minutes after injection. The affected side will show an often marked delay in time to peak activity. When the stenosis is less severe, delayed excretion can be the sole renographic abnormality (figure 1, C, D and E).

When used without ACE inhibition, renal scintigraphy has unacceptably low sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of renovascular hypertension.[15] The use of ACE inhibitors increases the abnormalities in accumulation and excretion of radionuclide agent and thereby improves the sensitivity and specificity of the renogram.[11] In patient populations with a high prevalence of the disease, various investigators have found its sensitivity to be 91 to 94 percent, with a specificity of 93 to 97 percent.[11,16] In patients with clinical clues suggestive of renovascular hypertension, this test has a negative predictive value of greater than 95 percent, and a negative test result indicates that further work-up is unnecessary.[16] The test is not this sensitive in patients with bilateral renal artery stenosis or in patients with stenosis to a solitary functioning kidney.[12]

Patients undergoing captopril-augmented renal scintigraphy should receive preprocedure instructions from the radiology center performing the test. Many protocols have specific requirements regarding salt intake, hydration and discontinuance of ACE-inhibitor medications several days before testing. Some centers give preprocedure intravenous hydration and/or a postprocedure diuretic agent to improve the test sensitivity and specificity.

Alternative Noninvasive Diagnostic Tests

Some of the alternative noninvasive tests for diagnosing renal artery stenosis include intravenous pyelography, the captopril test, magnetic resonance angiography and Doppler flow studies. Intravenous pyelography is less sensitive and less specific than the other methods,[17] and its sizable dye load and radiation dose have greatly diminished its role in the diagnosis of renovascular hypertension.

In the captopril test, which can be done in the physician's office, plasma renin activity is measured before and after an oral dose of captopril. The renal arteriolar changes that occur in patients with accelerated hypertension of any etiology (e.g., vasculitis, arterial dissection) may cause false-positive test results. The captopril test is relatively safe and inexpensive, but studies have shown a widely variable sensitivity of 34 to 100 percent and a specificity of 66 to 95 percent.[12] Recent or concurrent intake of antihypertensive medications, including diuretics, and a serum creatinine level of more than 1.5 mg per dL reportedly affect the accuracy of results.

Although magnetic resonance imaging does not require arteriotomy or the use of iodine contrast media, it may exaggerate the severity of the stenosis. Interpretation of films often lacks sufficient certainty to preclude the need for arteriography.[18] The diagnostic value of color-flow Doppler technology is highly operator-dependent. Even in specialized centers, up to 15 percent of studies were technically inadequate.[12] Doppler studies have difficulty detecting the distal segment of the renal artery, stenoses in branch arteries and the presence of an accessory artery. This method is better suited for detection of stenosis in the transplant renal artery or may be helpful in the follow-up after revascularization of a renal artery stenosis.[19]

While angiography is the gold standard for delineation of renal artery anatomy, it provides no information regarding the functional significance of a detected stenosis. The most commonly employed test for determining if a stenosis is significant and the patient will therefore benefit from revascularization is selective renal vein renin measurement. In this procedure, blood samples are obtained from the inferior vena cave and the renal veins. High concentrations of renin in a renal vein blood sample suggest renovascular hypertension in the presence of stenosis. This procedure is obviously invasive, as it involves selective catheterization of those veins.

Final Comment

The detection of renal artery stenosis is a difficult undertaking. All of the diagnostic methods discussed above perform best when undertaken on a selected population with a higher prevalence of disease. The prevalence of renovascular hypertension in unselected hypertensive patients is too low to justify widespread screening with any of the presently available tests. Captopril-augmented renal scintigraphy is a widely available noninvasive test with a dual advantage: it can be used to detect renal arterial stenosis and, when positive, can also predict response to treatment.[13]

REFERENCES

[1.] Lewin A, Blaufox MD, Castle H, Entwisle G, Langford H. Apparent prevalence of curable hypertension in the Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program. Arch Intern Med 1985;145:424-7.

[2.] Davis BA, Crook JE, Vestal RE, Oates JA. Prevalence of renovascular hypertension in patients with grade III or IV hypertensive retinopathy. N Engl J Med 1979;301:1273-6.

[3.] Brunner HR. ACE inhibitors in renal disease. Kidney Int 1992;42:463-79.

[4.] Choudhri AH, Cleland JG, Rowlands PC, Tran TL, McCarty M, al-Kutoubi MA. Unsuspected renal artery stenosis in peripheral vascular disease. BMJ 1990:301:1197-8.

[5.] Working Group on Renovascular Hypertension. Detection, evaluation, and treatment of renovascular hypertension: final report. Arch Intern Med 1987:147:820-9.

[6.] Svetkey LP, Kadir S, Dunnick NR, Smith SR, Dunham CB, Lambert M, et al. Similar prevalence of renovascular hypertension in selected blacks and whites. Hypertension 1991;17:678-83.

[7.] Munichoodappa C, D'Elia JA, Libertino JA, Gleason RE, Christlieb AR. Renal artery stenosis in hypertensive diabetics. J Urol 1979,121:555-8.

[8.] Easterling TR, Brateng D, Goldman ML, Strandness DE, Zaccardi MJ. Renal vascular hypertension during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 1991;78;921-5.

[9.] Saint-Georges G, Aube M. Safety of outpatient angiography: a prospective study. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1985;144:235-6.

[10.] Parfrey PS, Griffiths SM, Barrett BJ, Paul MD, Genge M, Withers J, et al. Contrast material-induced renal failure in patients with diabetes mellitus, renal insufficiency, or both. A prospective controlled study. N Engl J Med 1989;320:143-9.

[11.] The role of captopril scintigraphy in the diagnosis and management of renovascular hypertension: a consensus conference, Cleveland, Ohio, November 28-9,1990. Am J Hypertens 1991,4:661S-752S.

[12.] Davidson RA, Wilcox CS. Newer tests for the diagnosis of renal vascular disease. JAMA 1992;268: 3353-8 [Published erratum appears in JAMA 1993; 269:1508].

[13.] Dondi M, Fanti S, De Fabritiis A, Zuccala A, Gaggi R, Mirelli M, et al. Prognostic value of captopril renal scintigraphy in renovascular hypertension. J Nucl Med 1992;33:2040-4.

[14.] Mann SJ, Pickering TG, Sos TA, Uzzo RG, Sarkar S, Friend K, et al. Captopril renography in the diagnosis of renal artery stenosis: accuracy and limitations. Am J Med 1991;90:30-40.

[15.] Pickering TG. The role of laboratory testing in the diagnosis of renovascular hypertension. Clin Chem 1991;37:1831-7.

[16.] Mann SJ, Pickering TG. Detection of renovascular hypertension. State of the art: 1992. Ann Intern Med 1992;117:845-53.

[17.] Havey RJ, Krumlovsky F, delGreco F, Martin HG. Screening for renovascular hypertension. Is renal digital-subtraction angiography the preferred non-invasive test? JAMA 1985;254:388-93.

[18.] Debatin JF, Grist T, Svetkey L, Sostman D, Spritzer C. MR angiography: screening examination for renovascular hypertension?[Abstract] Am J Hypertension 1991;4:38A.

[19.] Taylor KJ, Morse SS, Rigsby CM, Bia M, Schiff M. Vascular complications in renal allografts: detection with duplex Doppler US. Radiology 1987;162:31-8.

QURESH T. KHAIRULLAH, M.D. is currently staff physician in the Department of Medicine, Division of Nephrology, at St. John Hospital, Detroit. Dr. Khairullah is a graduate of Bombay University, Bombay, India, and completed medical training at Sion Hospital, Lokmanya Tilak Municipal Medical College, Bombay, a residency in internal medicine at Bon Secours Hospital, Grosse Pointe, Mich., and a fellowship in nephrology at the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics.

DOUGLAS L. SOMERS, M.D. is assistant professor in the Division of Nephrology at the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics. Dr. Somers graduated from Saint Louis University School of Medicine and completed a residency in internal medicine at the Mayo Graduate School of Medicine, Rochester, Minn.

RECAYI AKTAY, M.D. is currently a resident in diagnostic radiology at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee. A graduate of Istanbul University Cerrahpasa School of Medicine, Dr. Aktay trained in nuclear medicine at the University of Istanbul Hospital and the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City.

Address correspondence to Quresh T Khairullah, M.D., 945 Ballantyne, Grosse Pointe Shores, MI 48236.

Coordinator of this series are Thomas J. Barloon, M.D., associate professor of radiology, and George R. Bergus, M.D., assistant professor of family practice, both at the University of Iowa College of Medicine, Iowa City.

COPYRIGHT 1997 American Academy of Family Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group