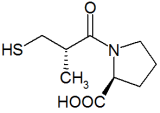

Tight control of blood pressure in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (formerly known as non-insulinEdependent diabetes mellitus) significantly reduces both microvascular and macrovascular complications. When blood pressure is controlled, the risk of stroke is reduced by 44 percent, the risk of microvascular disease is reduced by 37 percent and the risk of any diabetes-related complication is reduced by 24 percent. Beta-blocking agents and angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors have potential advantages in hypertensive patients with diabetes. ACE inhibitors may have a protective effect on renal microvascular disease and reduce heart failure mortality. Beta blockers reduce cardiac mortality after myocardial infarction and are effective in treating heart failure. The UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group directly compared the efficacy of captopril and atenolol in reducing the incidence of clinical complications in hypertensive patients with type 2 diabetes.

Patients were recruited as part of a large multicenter study of diabetes treatments involving 20 centers in Britain. Of the hypertensive patients with type 2 diabetes allocated to "tight" control, 400 were allocated to captopril therapy and 358 to atenolol therapy. Captopril was started at a dosage of 25 mg twice daily, increasing to a dosage of 50 mg twice daily; the goal was to achieve a systolic blood pressure less than 150 mm Hg and a diastolic blood pressure less than 85 mm Hg. Atenolol was started at a dosage of 50 mg daily, increasing to 100 mg daily if necessary. If control was not achieved, other agents were added in sequence, beginning with furosemide, followed by slow-release nifedipine, methyldopa and prazosin. Patients were monitored for control of diabetes, hypertension and evidence of any of 21 clinical end points. The duration of follow-up was nine years.

The two groups of patients were similar in age, body mass index, clinical status, and severity of diabetes and hypertension. Patient compliance was similar in both groups during the first four years of the study, but significantly more patients discontinued using atenolol later in the study. Overall, 80 percent of those assigned to captopril and 74 percent of those assigned to atenolol received treatment during the entire follow-up period. Three or more agents were required to achieve control in 27 percent of the captopril patients and in 31 percent of the atenolol patients. The two groups of patients achieved similar reductions in blood pressure (the captopril group to 144/83 mm Hg and the atenolol group to 143/81 mm Hg); patients who were not assigned to "tight" control -- and thus did not take captopril or atenolol -- had a mean blood pressure of 154/87 mm Hg over the nine-year period. Patients allocated to atenolol gained slightly more weight and had slightly higher glycated hemoglobin concentrations during the first four years of the study.

The incidence of all deaths and deaths associated with diabetes was similar in both groups. In addition, no statistically significant differences were found in any of the clinical end points. In each of the major categories of macrovascular disease, atenolol showed slight advantages over captopril, but none that came close to statistical significance. After nine years of follow-up, 31 percent of patients in the captopril group and 37 percent of those assigned to atenolol showed deterioration in retinopathy. Clinical albuminuria developed in 5 percent of patients in the captopril group and in 9 percent of patients in the atenolol group. These measures of renal function as well as others showed no statistical differences between the two treatments.

The authors conclude that both agents effectively and safely lower blood pressure and reduce the risk of fatal and nonfatal microvascular and macrovascular complications in patients with diabetes. The specific renal protection of ACE inhibitors was not apparent in this study. The choice of agent should be made on an individual basis for hypertensive patients who have type 2 diabetes.

UK Prospective Study Group. Efficacy of atenolol and captopril in reducing risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes: UKPDS 39. BMJ September 12, 1998;317:713-20.

editor's note: September issues of the two major British journals, BMJ and Lancet, contain several papers and commentary on type 2 diabetes. This condition is so prevalent in practice that there is a tendency to become complacent about its power to harm patients and to adopt a generally less aggressive attitude toward its management. The prevalence of type 2 diabetes is expected to increase and the total number of people affected worldwide is expected to rise from 110 million to over 200 million by the year 2010. These people will be at substantial risk for multiple conditions caused or exacerbated by diabetes. In particular, the 40 percent of patients who also become hypertensive before 45 years of age are at significant risk for vascular disease. Current reports validate the benefits of controlling blood glucose and blood pressure levels. Long-term studies showed reductions of over 40 percent in stroke and 30 percent in retinopathy, and reductions in multiple other end points, and in circumstances similar to most practice environments. This good news should re-energize efforts to manage patients with type 2 diabetes in everyday practice. The studies also indicate that we are on the threshold of a much more sophisticated approach to this common condition. Rather than taking a "one hypoglycemic agent fits all" approach, the next decade is likely to provide the information and medication necessary to tailor therapy to specific characteristics of each patient. Although we will be managing a greater number of patients with diabetes in the future, we can look forward to providing each with a regimen that offers real prospects of vigorous daily life and minimal risk of catastrophic complications.

COPYRIGHT 1999 American Academy of Family Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2000 Gale Group