INTRODUCTION

The use of cocaine in the form of "crack" has increased dramatically in the metropolitan Minneapolis-St. Paul area just as it has in the rest of the country. The latest drug abuse indicators for the Minneapolis-St. Paul metropolitan area as of December 1988 indicate that, while mention of heroin, morphine, and marijuana has remained relatively static during the last 4 years in emergency room documentation of illicit substances, cocaine use has increased by 300-400% in the last 24 months. Emergency room cocaine references indicate that in 1987 about 34% of drug-related contacts involved intravenous cocaine use and about 38% involved crack or smoked cocaine [1].

Crack is the form of cocaine which can be smoked. It is a crystalline "rock" which is immediately ready for igniting in a pipe or smoking apparatus. The cocaine-rich vapors enter the pulmonary vascular bed directly, return to the left side of the heart and pumped immediately to the brain. It may be that laminar flow maintains a concentrated bolus of cocaine. The first pulse of euphoric central nervous system stimulation occurs within 7-10 s of the initial inhalation. By contrast, intravenous administration of cocaine requires 30-45 s for the initial CNS effects to be experienced by the user [2], because it must travel through the venous system, right heart, pulmonary bed, left heart, into the general arterial system, and up to the brain. Crack reinforcement can be so strong that the crack smoker becomes intensely involved in a ritualized ceremony of lighting and relighting the pipe every 2 to 3 min to attempt to sustain the original cocaine-induced euphoria.

From the point of view of the user, the advantages of purchasing crack are twofold. First, the cocaine rock is immediately able to be smoked without any extraction procedure ("freebasing"). Second, the unit price on the street has been dramatically lowered for the range of small ($10-$25) purchases. The advantage to the seller is that crack markedly inflates the milligram price of cocaine. For example, an ounce of cocaine powder may be purchased for approximately $2,000. This can be converted to over $6,000 street value of crack by freebase extraction which requires little more than the purchase of baking soda as an alkalinizing agent. When small units of cocaine powder are purchased on the street, they are usually adulterated with lactose, mannitol, or local anesthetics such as lidocaine or procaine. Although the crack cocaine addict is purchasing a much smaller amount of cocaine by weight, he is getting a purer product, immediately ready for use, with virtually instant euphorogenic properties. Hence, the crack epidemic.

Most experienced heavy cocaine users have a predominant route of administration. Drug abusers with extensive past IV drug experience generally prefer cocaine by the intravenous route. They claim more intense and prolonged euphoric experience. They also have more control of the process and repeatedly will draw blood back into the syringe to dilute remaining cocaine, creating several doses of diminishing intensity ("register" or "boot"). For most non-IV users, and for some IV users, crack smoking is the route of choice, and crack use becomes the compulsive center of their lives.

During the past year we have developed an experimental pharmacologic treatment for cocaine abusers [3] based on the hypothesis that craving in humans may be the behavioral manifestation of the neurophysiological event of "kindling" which, in animals, can be caused by cocaine. The term "kindling" refers to the progressive facilitation of neuronal firing in discrete regions of the brain, elicited by temporally spaced exposure to specific consistent pharmacologic or electrical stimuli. Since 1929, cocaine has been shown to produce increasing psychomotor excitability with eventual seizures [4,5]. The presence of seizures was the original meaning of kindling. Other psychomotor stimulants, local anesthetics, and electrical stimuli have similarly been foun to produce kindling [5-7]. Temporally spaced injections more than 24 h apart, of fixed subconvulsive doses of cocaine, were found to elicit major motor seizures as an endpoint in the kindling process, but with a variety of midstage kindling "behavioral" responses [8]. The recognition of intermediate behavioral changes has given kindling a wider definition. Animals of all species studied developed specific stereotype and disruption of learned behavior before they progressed to major motor seizures [8]. Limbic system structures, especially the amygdala and hippocampus, have been found to produce prominent activity in response to cocaine administration [5,9]. Once the brain has been kindled by repeated exposure to cocaine, the neuronal sensitization persists for months after exposure to the drug [10,11].

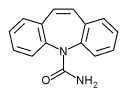

Carbamazepine is a clinically useful anticonvulsant which affects temporal lobe dysfunction [12]. In animals, carbamazepine selectively inhibits early, i.e., developmental, phases of pharmacological kindling induced by local anesthetics [13]. It also blocks the late phases of electrically kindled seizures in animals [13]. Based on these opposite effects on kindling, it was hypothesized by one of us (J.A.H.) several years ago that carbamazepine may effectively treat cocaine abuse and particularly cocaine craving.

METHODOLOGY

The University of Minnesota Chemical Dependency Treatment Program has treated 16 predominantly crack cocaine users with this new pharmacologic approach as part of a larger group of 26 cocaine users in an open clinical trial. These 16 crack users include 12 who have previously been reported in a Letter to the Editor published in Lancet [14], which described early treatment results of the whole group without distinction as to route of cocaine administration. A systematic reappraisal of a clinical treatment approach, such as this, can only provide tentative conclusions as to the potential overall usefulness or efficacy, and safety, of this pharmacological approach.

At intake, all patients were clinically assessed by a psychiatry resident for diagnosis and treatment level referral. Hospitalization, if indicated, was based on usual clinical grounds for the University of Minnesota inpatient chemical dependency program, which is designed as a brief (10-14 days) introduction to subsequent day hospital outpatient rehabilitation treatment. Beginning in early 1988, all cocaine-using patients who presented for treatment at the program received carbamazepine as a pharmacologic adjunct to their chemical dependency treatment. Patients were not separately selected for carbamazepine treatment. Use of other medications was based on clinical diagnosis judgment (this sample included one bipolar depressed, three unipolar depressed patients). The University of Minnesota is a tertiary referral Chemical Dependency Treatment Program which focuses on "special populations," including mentally ill, chemically-dependent patients (MI-CD). Treatment is individually designed based on diagnoses and previous clinical history, provided within the milieu of an abstinence model-rehabilitation setting.

Whether as inpatients or outpatients, supplementing the pharmacologic treatment, patients were asked to attend a weekly 2-h outpatient cocaine group therapy. The weekly therapy session included several components; for example, drug abuse education, relapse prevention strategies, development of coping skills, etc. Neither cocaine abstinence nor carbamazepine compliance was a requirement for participation in this open group. In this clinical trial, only the Tegretol brand of carbamazepine in tablet form was used because it has more reliable pharmacokinetic properties than have the generic brands [15]. In addition, significantly variable GI absorption has been noted with generic carbamazepine [16].

In addition to the carbamazepine, several patients were either tried or maintained on other medications at some point (lithium and imipramine 1, desipramine 1, amitriptyline 1, doxepin 1). Patients were individually titrated to eliminate or minimize craving for cocaine within tolerable carbamazepine side effects limits. A b.i.d. schedule beginning at 100 mg was considered optimal based on pharmacologic considerations. Dosage increases of 100-200 mg every 2-4 days were tolerated well. The most frequent side effects were drowsiness, "spacey feelings," dizziness, or itchiness. All were transient. Significant skin rash and marrow suppression were not seen.

In this open trial, the response to treatment was monitored clinically three ways. First, compliance with medication was determined by patient interview at each visit, covering the previous time interval. Participation in the program was not contingent on carbamazepine compliance or on abstinence from cocaine use. There were no penalties for noncompliance or cocaine relapse, and therefore no incentive to lie or minimize drug use. While urine drug screens were obtained as often as possible, frequency was limited by cost issues, and systematic data were not obtained. Urinalysis results were used to verify self-report data where possible. Second, the number of days the individual used or abstained from cocaine during the 100 days prior to entering the treatment program was recorded at the intake interview. At each subsequent visit, the number of days of cocaine use and cocaine abstinence were obtained by patient interview and confirmed by group discussion during the therapy session. Days abstinent per 100 days before treatment was compared to the number of days abstinent while in the treatment program, with mean and standard deviation evaluated by a students' t-test. Third, each clinician provided a judgment at each visit comparing overall life functioning to the 100 days pretreatment using the clinical global scale.

Most subjects could be contacted for purposes of collecting follow-up data, whether or not they had continued in treatment. Furthermore, the relationship of the clinical staff to these patients was comfortable, and the programmatic philosophy flexible enough to allow ongoing contact by former clients on an ad lib basis.

RESULTS

These 16 crack cocaine users included 10 patients who also had a history of intravenous drug use, seven patients in a methadone maintenance program for past heroin addiction, seven women, and ten Blacks. Their average age was 32.8 years. During the 100 days preceding treatment, these 16 subjects each used cocaine by all routes an average of 70.9 days. Demographic and drug use descriptors of the group are presented in Table 1. The current results are based on 2,016 days of risk for the total of 16 individuals, or an average of 126 days (about 4 months) per patient, with a range of 21-252 days at risk, dated from being first offered the carbamazepine treatment.

There are several ways to assess effectiveness, or outcome, in an open series: 1) improvement in symptoms; here, increase in days of abstinence from cocaine use, on a case-by-case basis; 2) compliance with treatment; here, regular use of carbamazepine; and, 3) correlation between treatment compliance and remission of symptoms. Four different strategies were employed to classify crack users in order to assess the effectiveness of carbamazepine for crack use. Self-reported change in the proportion of days using cocaine before and after the carbamazepine intervention was the outcome measure used for each analysis. Each patient was followed after intervention, but the length of follow-up varied from patient to patient. The algorithm which follows defines the outcome variable for the subsequent three analyses. It describes the change in proportion of days of cocaine use with intervention.

Outcome = days of using cocaine before intervention / 100 days - total number of days of using cocaine after intervention / total number of days in study following intervention

Analysis A: The 16 crack users were divided into three groups based on the clinical judgment of the nonblinded investigators:

1) Highly successful group (n = 7) 2) Partially successfull group (n = 6) 3) Unsuccessful group (n = 3)

Based on self-report, the highly successful group reduced their cocaine use from 65 days per 100 days pretreatment to less than 1 day (0.7) per 100 days with

treatment. The partially successful group went from 73 days of use to 26 days of use per hundred; the unsuccessful group went from 80 days to 67 days. Using the defined outcome variable, an analysis of variance was performed, comparing the three groups. Even with the small sample sizes, a statistically significant overall difference was found among the three groups (F = 4.26, p = .037, df = 2,13). Pairwise comparisons were then employed using the Scheffe procedure to further assess where the significant differences occurred. Among the three groups, the "highly successful group" was significantly different from the "unsuccessful group" in proportionate decrease in use. Table 2 indicates the mean proportion of days of cocaine use for each of the three treatment groups. In comparing the pretreatment to posttreatment mean proportions, only the highly successful and the partially successful groups showed significant declines in cocaine use after intervention.

Analysis B: The second method of evaluating outcome, compliance, was determined by self-report during the clinical interview. Analysis revealed that 6 patients used the medication at least 90% of the days at risk following discharge. The mean number of days at risk for this compliant group was 107. An additional 5 patients took the medication for at least 2 weeks but less than 90% of the days at risk. This partially compliant group averaged 189 days at risk. The remaining 5 patients demonstrated poor or nonrcompliance. This noncompliant group averaged 190 days at risk.

While it appears that the noncompliant and partially compliant patients averaged more days in treatment, the greater length of days at follow up actually reflects the order of admission into the clinical series. The first several patients treated received a similar carbamazepine induction schedule to manic patients, beginning with 2-400 mg per day and increasing quickly. This proved intolerable because

[TABULAR DATA OMITTED]

of sedation and dizziness. Subsequently, we learned to go "lower and slower" and individualize induction. Cocaine users appear extraordinarily sensitive to carbamazepine. This may relate to the proposed "kindling" explanation for craving which we have outlined elsewhere [17].

Self-reported compliance with carbamazepine was associated very strongly with successful abstinence from cocaine use in all forms. Overall, the compliant group had the best outcome, reducing their cocaine use from 65 days per 100 days pretreatment to 0.8 days per 100 days of risk with treatment (t = 4,83, p = .0025). They averaged 106 days of carbamazepine use in that same period. For these 6 subjects, virtually 100% self-reported compliance with carbamazepine use was associated with virtually complete elimination of cocaine use. As shown in Table 3, there was also improvement in the partially compliant and noncompliant groups as well. However, the level of postintervention cocaine use was substantially higher for these groups: 43 days per 100 for the partially compliant group and 29 days per 100 for the noncompliant group. For the 5 partially compliant subjects, a reduction of 46% in their cocaine use was achieved, with a 41% rate of pharmacologic compliance.

The same statistical analyses (analysis of variance and pairwise comparisons) were performed as in Analysis A. Here, there was no significant difference in proportion of change of use before and with treatment among the three groups since significant improvement occurred in all three groups.

Demographic and drug use data for the three compliance groups are presented in Table 4. As can be seen, the partially compliant group tended to be the oldest (39.2 years of age) with the most years of substance abuse (22 years), the most

[TABULAR DATA OMITTED]

years of cocaine use (8.6 years), the largest number of previous treatment attempts (4.6), the largest number of lifetime arrests (12.4), and an average of 32.8 lifetime months in jail. The noncompliant group had the highest proportion of women (4 of 5), but was otherwise not different from the compliant group.

There were five noncompliant patients. For the purposes of this analysis, noncompliance was defined as less than 14 days of carbamazepine use. These 5 patients actually consisted of two groups: 3 patients with a total of 96 days at risk and 2 patients with a total of 332 days at risk. The 3 patients totaling 96 days at risk averaged 32 days of contact time, 8 days of carbamazepine use, and 1 day apiece of cocaine use. Each then disappeared from treatment and follow up, presumably having relapsed. The two patients totaling 332 days at risk averaged 4 days of carbamazepine use, 129 days f cocaine use apiece (77%), but stayed in intermittent contact with the program so that their continued cocaine use could be documented. These two crack users may be considered representative of the likely outcome for a noncompliant crack population. While no control group exists in such a study, the outcome of the 5 noncompliers and the 5 partial compliers may be predictive.

Because an intervention effect was seen in the total noncompliant group (including the patients who were in contact for about 1 month apiece and then disappeared), the role of carbamazepine in this effect remained uncertain. A third strategy was therefore employed that assessed the relationship of carbamazepine compliance to reduction in cocaine use more directly.

Analysis C: This method relates the change in proportion of days using cocaine to the proportion of days taking carbamazepine. A Pearson product moment correlation was calculated for these two variables across all 16 crack-using patients. This significant correlation (r = .4409, n = .16, p = .043, 1-tailed) was indicative of an association (95% probability) between compliance in taking carbamazepine and reduction in days of using cocaine (pre- vs postintervention).

Analysis D: Of the 16 crack-using patients, 15 could be categorized either as predominately crack using (n = 10) or predominantly IV cocaine-using (n = 5). The sixteenth patient's predominant use pattern was nasal inhalation, so he was eliminated from the next set of analyses. Although the predominantly IV-using group had a smaller mean reduction in the prepost proportion of days using (x = .3463) compared to the predominantly crack using group (x = .5695), this finding was not statistically significant. A two-way analysis of variance also indicated that there was no moderating or interactive effect of predominant use patterns with success group (high vs partial vs unsuccessful), nor with compliance group (complete vs partial vs noncompliant) on the mean proportion of change in use before versus after the carbamazepine intervention.

CONCLUSION

These are preliminary, tentative results from a methodologically limited, open-label treatment attempt. As such, great caution must be exercised in interpreting the results.

Crack has been considered to be the most fulminant form of cocaine use, and crack cocaine use has been found to be the most difficult with which to achieve any treatment remission [16]. The crack patients treated here represent a portion of the cocaine-using population most deeply involved in cocaine use, other drug use, antisocial behavior, and failed previous treatment.

In light of the general treatment pessimism with this substance [18, 19], and the severity of the patient group treated, these results are encouraging. It would appear that compliance with carbamazepine ingestion correlated directly with successful days of abstinence from cocaine use. Those subjects who achieved virtually total carbamazepine compliance also achieved virtually total abstinence. Those subjects who demonstrated partial compliance, on about 41% of the days possible, also noted a substantial reduction of 46% in their days of cocaine use. The short-term reduction of cocaine use in the group of pharmacologically noncompliant subjects may, in part, have resulted from participation in the other aspects of the treatment program. The success of the carbamazepine intervention occurred regardless of whether crack use of cocaine or intravenous use of cocaine was the preferred route.

Clinically, very clear differences were apparent among subjects. Successful and partially successful patients were more likely to continue to attend group, sharing recovery and relapse experiences, and, over time, gaining needed insight into high risk situations, relapse prevention, and personal factors. The carbamazepine appeared to provide them with a return of control of their cocaine use, by their report subjectively reducing the compulsion, or craving to use, which had subverted past treatment attempts.

In summary, among 16 crack cocaine users, compliance with carbamazepine use was associated with successful abstinence from cocaine use, in approximate proportion to the days of pharmacologic compliance with good patient comfort and safety. These preliminary data have encouraged us to plan a large-scale placebo controlled, double blind clinical trial.

REFERENCES

[1] Falkowski, C. L., Drug Abuse Indicators in the Minneapolis/St. Paul Metropolitan Area, Annual Report, Minnesota Department of Human Services, Chemical Dependency Program Division, St. Paul, Minnesota, December, 1988.

[2] Perez-Reyes, M., DiGuiseppi, B. S., Ondrusek, G., Jeffcoat, A. R., and Cook, C. E., Free-base cocaine smoking, Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 32:459-465 (October 1982).

[3] Halikas, J. A., Kemp, K. D., Kuhn, K. L., Carlson, G. A., and Crea, F. S., Carbamazepine for cocaine addiction?, Lancet 1:623-624 (1989).

[4] Tatum, A. T., and Seevers, M. H., Experimental cocaine addiction, J. Pharmacol, Exp. Ther. 36:401-410 (1929).

[5] Post, R. M., Kopanda, R T., and Black, K. E., Progressive effects of cocaine on behavior and central amine metabolism in Rhesus monkeys: Relationship to kindling and psychosis, Biol. Psychiatry 11:403-419 (1976).

[6] Goddard, G. V. McIntyre, D. C., and Leech, C. K., A permanent change in brain functioning resultig from daily electrical stimulation, Exp. Neurol. 25:295 (1969).

[7] Post, R. M., and Kopanda, R. T., Cocaine, kindling and psychosis, Am. J. Psychiary 133:627-634 (1976).

[8] Ellinwood, E. H., and Kilbey, M. M., Chronic stimulant intoxication models of psychosis, in Animals Models in Psychiary and Neurology (E. Hanin and E. Usdin, eds.), Pergamon Press, New York, 1977, pp. 61-74.

[9] Eidelberg, E., Lesse, H., and Gault, F. P., 1963. An experimental model of temporal lobe epilepsy: Studies of the convulsant of cocaine, in EEG and Behavior (G. H. Glaser, ed.), Basic Books, New York, 1963, pp. 272-283.

[10] Pollack, D. C., The kindling phenomenon and a clinical application: The procaine, Psychiatr. J. Univ. Ottawa 10(4):185-192 (1985).

[11] Post, R. M., Ballenger, J. C., Uhde, T. W. Putman, F. W., and Bunny, W. E. 1981. Kindling and drug sensitization: Implications for the progressive development of psychopathology, and treatment with carbamazepine, in The Psychopharmacology of Anti-convulsants (M. Sandler, ed.), Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1981, pp. 29-48.

[12] Penry, J. K., and Daly, D. D., Complex partial seizures and their treatment, Adv. Neurol. 11.

[13] Post, R. M., Time course of clinical effects of carbamazepine: Implication for mechanism of action, J. Clin. Psychiatry. 49(Suppl.(4(1):35-46 (1988).

[14] Halikas, J. A., Kemp, K., Kuhn, K., Carlson, G., and Crea, F., Carbamazepine for cocaine addiction?, Lancer 1:623-624 (1989).

[15] Sachdeo, R. C., and Belendink, G., Generic versus branded carbamazepine, Lancet 1:1432 (1987).

[16] Neppe, V. M., Tucker, G. J., and Wilensky, A. J., Introduction: Fundamentals of carbamazepine use in neuropsychiatry, J. Clin. Psychiatry 49(Suppl):4 (1988).

[17] Halikas, J. A., and Kuhn, K. L., A possible neurophysiological basis of cocaine craving, Ann. Clin. Psychiatry, In Press.

[18] Joseph, S. C., A methadone clone for cocaine, New York Times, January 11, 1989.

[19] Gawin, F. H., and Ellinwood, E. H., Cocaine and other stimulants, N. Engl. J. Med. 318:1173-1182 (1988).

COPYRIGHT 1992 Taylor & Francis Ltd.

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group