Abstract

Although cutaneous reactions from antineoplastic therapy are common, a reticulate pattern of hyperpigmentation has not been frequently reported in the literature. We report 2 cases of reticulate hyperpigmentation associated with cancer chemotherapy with 5-fluorouracil and idarubicin. These 2 cases serve to raise awareness of this particular pattern of hyperpigmentation as a potential side effect of chemotherapeutic regimens.

Case 1

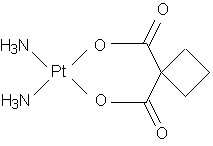

A 63-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and squamous cell carcinoma of the floor of the mouth and nasal tip developed a reticulated rash while receiving chemotherapy for mucoid epidermoid carcinoma of the right parotid gland. She initially presented with squamous cell carcinoma of the floor of the mouth. Three years following surgical resection, she had a recurrence at the uvula for which she received radiotherapy. Two years later, the patient developed squamous cell carcinoma of the nasal tip that was resected with free flap reconstruction. One year after that, she was found to have mucoid epidermoid carcinoma of the right parotid gland. This was resected and the patient began treatment with concomitant chemoradiotherapy with cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil. She developed hearing loss from the cisplatin after the second cycle, so her third cycle was changed to carboplatin and 5-fluorouracil. Three days into the third cycle, the patient developed a reticulated erythematous rash on her back and legs. The erythema eventually changed first to a violaceous and then to a brownish discoloration. The patient was seen by the dermatology service during admission for her fourth cycle of chemotherapy with 5-fluorouracil and carboplatin. At that time, she was noted to have a reticulated, hyperpigmented macular eruption on her back (Figure 1), posterior thighs, and popliteal fossae. There was no erythema or scale, and the patient was entirely asymptomatic from this eruption. This patient's reticulate hyperpigmentation was attributed to her treatment with 5-fluorouracil. Although she had also received carboplatin, this was not felt to be the etiology since platinum-based agents such as cisplatin and carboplatin are not known to cause significant cutaneous side effects.

[FIGURE 1 OMITTED]

[FIGURE 2 OMITTED]

Case 2

A 51-year-old woman with a history of hepatitis C and recently diagnosed acute myelogenous leukemia was admitted to the hospital for induction chemotherapy with idarubicin and cytarabine. Her hospital course was complicated by neutropenic fever, for which she was treated initially with vancomycin and cefepime. This was later changed to linezolid for treatment of vancomycin-resistant enterococcal bacteremia and typhlitis. The patient's infection eventually improved, her blood counts recovered, and she was discharged. She underwent a bone marrow biopsy one month later, and at that time she was found to have reticulated hyperpigmented patches on her lower back (Figure 2). She had not noticed this rash herself, and she had no associated symptoms. This reticulated hyperpigmentation was felt to be secondary to her treatment with idarubicin.

Discussion

A variety of cutaneous reactions occur commonly in patients receiving cancer chemotherapy. Nixon et al classified the skin changes that occur with chemotherapy into 3 categories: 1) changes related to cytotoxicity; 2) rashes and eruptions; and 3) pigment alterations. (1) Cytotoxic alterations occur with chemotherapeutic agents that interfere with the synthesis of nucleic acids or with ribosome function. These drugs include alkylating agents, antimetabolites, antitumor antibiotics, vinca alkaloids, nitrosoureas, and others. Cytotoxic reactions may manifest as local irritation, alopecia, and mucositis, and they typically resolve some time after the cessation of chemotherapy. Rashes and eruptions can occur with a wide variety of chemotherapy drugs. (2) For example, urticarial reactions have been described with doxorubicin, (3) toxic epidermal necrolysis has been reported with mithramycin, (4) and a folliculitis-like reaction has occurred with actinomycin D. (5)

Hyperpigmentation is a frequent and well-recognized side effect of cancer chemotherapy, and various patterns of pigmentation have been described. However, a reticulate pattern of hyperpigmentation has not been frequently reported in the literature. Various pigment alterations occur with a wide variety of antineoplastic agents and can affect the nails, hair, and skin. Darkening of the nails and nail beds has occurred with the anthracycline antibiotics doxorubicin and daunoubicin (6-8) as well as with the alkylating agents cyclophosphamide (9) and melphalan. (10) Singal et al described discrete hyperpigmentation in areas of skin occlusion in 2 children receiving treatment for metastatic sarcoma with cyclophosphamide, etoposide, and carboplatin. (11) Hyperpigmentation has also been described with hydroxyurea, which can cause increased pigmentation of either the skin or the nail beds. (12)

The first report of reticulate hyperpigmentation occurred in a patient receiving chemotherapy with bleomycin. Bleomycin has previously been associated with various patterns of hyperpigmentation, including flagellate pigmentation, (13) linear streaking, (14) and hyperpigmented striae distensae. (15) In 1990, Wright et al described a 55-year-old man with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma who developed symmetrical linear and reticulate streaks of hyperpigmentation on his trunk and limbs following treatment with bleomycin. (16) A punch biopsy taken from a linear area of hyperpigmentation showed an increased number of melanosomes with increased melanin production in the basal and suprabasal keratinocytes. Electron microscopic studies showed intracytoplasmic vacuoles felt to be the result of damage to the mitochondria.

Although 5-fluorouracil is also associated with a variety of patterns of hyperpigmentation, to our knowledge, this is only the second case of reticulate hyperpigmentation in a patient receiving 5-fluorouracil chemotherapy. More typically, 5-fluorouracil causes a photosensitivity reaction, with erythema and hyperpigmentation occurring on sunexposed areas. (17) Hrushesky first described hyperpigmentation of the epidermis overlying veins used for repeated infusions of 5-fluorouracil, suggesting the term "serpentine supravenous fluorouracil hyperpigmentation" because of the serpiginous appearance of the lesions. (18) Vukelja et al reported a case of serpentine hyperpigmentation in noninfusion areas in a patient treated with 5-fluorouracil for rectal adenocarcinoma. (19) In addition, dark brown pigmented macules on the palms, soles, and trunk have been described, (20) as has hyperpigmentation of the nails and palms. (21) In 1995, Allen et al described a patient who developed a widespread erythematous and pigmented reticulate eruption following infusional 5-fluorouracil for metastatic gastrointestinal carcinoma. (22) Like our patient, this patient had no associated symptoms, and he was noted to have gradual fading of the eruption without treatment over a period of 16 weeks.

Reticulate hyperpigmentation has not been previously reported with either cytarabine or idarubicin, which are used in combination for induction chemotherapy in acute myelogenous leukemia. Idarubicin shares many similarities to the other anthracycline antibiotics, doxorubicin, and daunorubicin. Previously described pigment changes with doxorubicin and daunorubicin include hyperpigmentation of the nails and nail beds, (6,23-25) hyperpigmentation of the periarticular skin on the dorsa of the hands, (7) and hyperpigmentation of the palms and soles. (26) In addition, Kroumpouzos et al described a case of generalized hyperpigmentation of the skin in association with daunorubicin. (27) To date, there has been only one case report of pigment alterations associated with idarubicin. Borecky et al described nail pigment changes similar to those seen with doxorubicin and daunorubicin in a patient with AML treated with idarubicin. (28) There have been no previous reports of generalized or reticulate hyperpigmentation associated with idarubicin.

Cytarabine, an antimetabolite, has very few associated cutaneous side effects. (29) Dermatologic reactions are rare and typically associated with high-dose cytarabine treatment. The most recognized manifestations include acral erythema, (30) neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis, (31) and, less commonly, cutaneous necrotizing vasculitis. (32) No cases of pigment alterations in association with cytarabine exist. Although in our second case, the possibility of cytarabine as the cause of the patient's reticulate hyperpigmentation must be considered, it is far less likely given that, in its many years of use, cytarabine has never been associated with pigment changes.

Although several theories exist, the exact mechanism by which chemotherapeutic agents increase skin pigmentation remains unknown. One proposed possibility in the case of the anthracycline antibiotics involves an increase in melanocyte stimulating hormone levels. (6,24) However, subsequent measurements of melanocyte stimulating hormone levels in patients with doxorubicin-associated hyperpigmentation revealed normal levels. (33) Another theory proposes a photosensitization via a "psoralen-like" reaction. (34) However, many of the cases of hyperpigmentation have occurred on non-sun-exposed areas of the body, making this less likely. Finally, the hyperpigmentation may occur as a result of increased melanogenesis in response to damage to the epidermal cells. In the case of bleomycin, it has been speculated that the reticulate pattern occurs because of the higher concentration of bleomycin in areas of the skin with a greater blood supply. (16)

Regardless of the etiology, no specific therapy exists for the treatment of reticulate hyperpigmentation. In both cases presented here, as with the previous cases associated with bleomycin and 5-fluorouracil, the patients had no symptoms associated with the eruptions. However, antipruritics and moisturizing ointments may be used if symptoms develop. Typically, the hyperpigmentation will fade gradually with time; however, in some cases, it may persist indefinitely. (16,22)

Conclusion

Reticulate hyperpigmentation is a rare but unique cutaneous reaction to antineoplastic chemotherapy. It has previously been seen in association with bleomycin and 5-fluorouracil. This article describes the second case caused by treatment with 5-fluorouracil as well as the first case associated with idarubicin. Knowledge of the appearance of this reaction as well as the potential etiologic agents will aid in the proper recognition and diagnosis of future cases.

References

1. Nixon DW, et al. Dermatologic changes after systemic cancer therapy. Cutis. 1981; 27(2):181-2, 186-8, 192-4.

2. Levantine A, Almeyda J. Drug reactions. XXIV. Cutaneous reactions to cytostatic agents. Br J Dermatol. 1974;90(2):239-42.

3. Souhami L, Feld R. Urticaria following intravenous doxorubicin administration. JAMA, 1978;240(15):1624-6.

4. Purpora D, Ahern MJ, Silverman N. Toxic epidermal necrolysis after mithramycin. N Engl J Med. 1978;299(25):1412.

5. Epstein EH Jr, Lutzner MA. Folliculitis induced by actinomycin D. N Engl J Med. 1969;281(20):1094-6.

6. Priestman TJ, James KW. Letter: Adriamycin and longitudinal pigmented banding of fingernails. Lancet. 1975;1(7920):1337-8.

7. Orr LE, McKernan JF. Pigmentation with doxorubicin therapy. Arch Dermatol. 1980;116(3):273.

8. Alagaratnam TT, Choi TK, Ong GB. Doxorubicin and hyperpigmentation. Aust N Z J Surg. 1982; 52(5):531-3.

9. Srikant M, et al. Cyclophosphamide-induced nail pigmentation. Br J Haematol. 2002;117(1):2.

10. Malacarne P, Zavagli G. Melphalan-induced melanonychia striata. Arch Dermatol Res. 1977; 258(1):81-3.

11. Singal R, et al. Discrete pigmentation after chemotherapy. Pediatr Dermatol. 1991;8(3):231-5.

12. Kennedy BJ, Smith LR, Goltz RW. Skin changes secondary to hydroxyurea therapy. Arch Dermatol. 1975;111(2):183-7.

13. Nigro MG, Hsu S. Bleomycin-induced flagellate pigmentation. Cutis. 2001;68(4):285-6.

14. Rademaker M, et al. Linear streaking due to bleomycin. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1987;12(6):457-9.

15. Tsuji T, Sawabe M. Hyperpigmentation in striae distensae after bleomycin treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28(3):503-5.

16. Wright AL, Bleehen SS, Champion AE. Reticulate pigmentation due to bleomycin: light- and electronmicroscopic studies. Dermatologica. 1990;180(4):255-7.

17. Falkson G, Schulz EJ. Skin changes in patients treated with 5-fluorouracil. Br J Dermatol. 1962;74:229-36.

18. Hrushesky WJ. Unusual pigmentary changes associated with 5-fluorouracil therapy. Cutis. 1980;26(2):181-2.

19. Vukelja SJ, et al. Unusual serpentine hyperpigmentation associated with 5-fluorouracil. Case report and review of cutaneous manifestations associated with systemic 5-fluorouracil. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25(5 Pt 2):905-8.

20. Cho KH, et al. Pigmented macules in patients treated with systemic 5-fluorouracil. J Dermatol. 1988;15(4):342-6.

21. Perlin E, Ahlgren JD. Pigmentary effects from the protracted infusion of 5-fluorouracil. Int J Dermatol. 1991; 30(1):43-4.

22. Allen BJ, Parker D, Wright AL. Reticulate pigmentation due to 5-fluorouracil. Int J Dermatol. 1995; 34(3):219-20.

23. Pratt CB, Shanks EC. Letter: Hyperpigmentation of nails from doxorubicin. JAMA. 1974;228(4):460.

24. Morris D, Aisner J, Wiernik PH. Horizontal pigmented banding of the nails in association with Adriamycin chemotherapy. Cancer Treat Rep. 1977;61(3):499-501.

25. deMarinis M, Hendricks A, Stoltzner G. Nail pigmentation with daunorubicin therapy. Ann Intern Med. 1978;89(4):516-7.

26. Law IP. Doxorubicin and unusual skin manifestations. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113(3):379-80.

27. Kroumpouzos G, Travers R, Allan A. Generalized hyperpigmentation with daunorubicin chemotherapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46(2 Suppl Case Reports):S1-3.

28. Borecky DJ, et al. Idarubicin-induced pigmentary changes of the nails. Cutis. 1997;59(4):203-4.

29. Adrian RM, Hood AF, Skarin AT. Mucocutaneous reactions to antineoplastic agents. CA Cancer J Clin. 1980;30(3):143-57.

30. Levine LE, et al. Distinctive acral erythema occurring during therapy for severe myelogenous leukemia. Arch Dermatol. 1985;121(1):102-4.

31. Flynn TC, et al. Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis: a distinctive rash associated with cytarabine therapy and acute leukemia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;11(4 Pt 1):584-90.

32. Ahmed I, et al. Cytosine arabinoside-induced vasculitis. Mayo Clin Proc. 1998;73(3):239-42.

33. Kew MC, et al. Melanocyte-stimulating-hormone levels in doxorubicin-induced hyperpigmentation. Lancet. 1977;1(8015):811.

34. Kelly TM, Fishman LM, Lessner HE. Hyperpigmentation with daunorubicin therapy. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120(2):262-3.

Address for Correspondence

Sylvia Hsu MD

Associate Professor

Department of Dermatology

Baylor College of Medicine

One Baylor Plaza, FB800

Houston, Texas 77030

Phone: 713.798.4046

Fax: 713.798.6923

e-mail: shsu@bcm.tmc.edu

Reena Jogi MD, Mary Garman MD, Josie Pielop MD, Ida Orengo MD, Sylvia Hsu MD

Department of Dermatology, Baylor College of Medicine

COPYRIGHT 2005 Journal of Drugs in Dermatology, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2005 Gale Group