Chagas disease (American trypanosomiasis) is caused by the protozoan parasite Trypanosoma cruzi. Chagas disease following solid-organ transplantation has occurred in Latin America, where Chagas disease is endemic, but has not been reported previously in the United States. This report describes three cases in the United States of T. cruzi infection associated with transplantation of organs from a single donor. CDC and the U.S. organ transplantation organizations will consider whether to recommend screening of potential donors for T. cruzi infection and, if so, which donors to screen, how to screen, and what to do if the screening tests are positive.

On April 23, 2001, a physician notified CDC of an acute case of Chagas disease. A woman aged 37 years who had received cadaveric kidney and pancreas transplants on March 5 returned to the hospital on April 19 for evaluation of a febrile illness. On April 23, T. cruzi trypomastigotes were identified on a peripheral blood smear (Figure 1). Subsequently, two other persons who had received organs from the same donor--a woman aged 32 years who had received the liver and a woman aged 69 years who had received the other kidney--were found to be infected with T. cruzi. Cultures of blood from all three recipients were positive for T. cruzi. The donor, an immigrant from Central America, presumably had been infected with T. cruzi; however, no specimens from the donor were available for testing.

After infection was detected, the recipients were treated with nifurtimox provided by the CDC Drug Service, which provides U.S.-licensed physicians with drugs that otherwise would not be available in the United States. The woman aged 69 years who had received a kidney was treated for approximately 4 months and, as of March 2002, has done well with no evidence of recurrence of T cruzi infection. The other two patients died. The recipient of the kidney and pancreas transplants, who was the most immunosuppressed of the three patients, experienced recurrent, symptomatic T. cruzi parasitemia several weeks after completing a 4-month course of treatment with nifurtimox. On October 8, she died of acute Chagasic myocarditis, 2 weeks into her second course of nifurtimox therapy. On July 8, after several weeks of nifurtimox therapy, the recipient of the liver died of sepsis and hepatic and renal failure, which were unrelated to T. cruzi infection.

Reported by: CF Zayas, MD, C Perlino, MD, A Caliendo, MD, D Jackson, MT(ASCP), EJ Martinez, MD, P To, MD, TG Heffron, MD, Emory Univ School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia. JL Logan, MD, Univ of Arizona College of Medicine, Tucson. BL Herwaldt, MD, AC Moore, MD, FJ Steurer, MS, C Bern, MD, JH Maguire, MD, Div of Parasitic Diseases, National Center for Infectious Diseases, CDC.

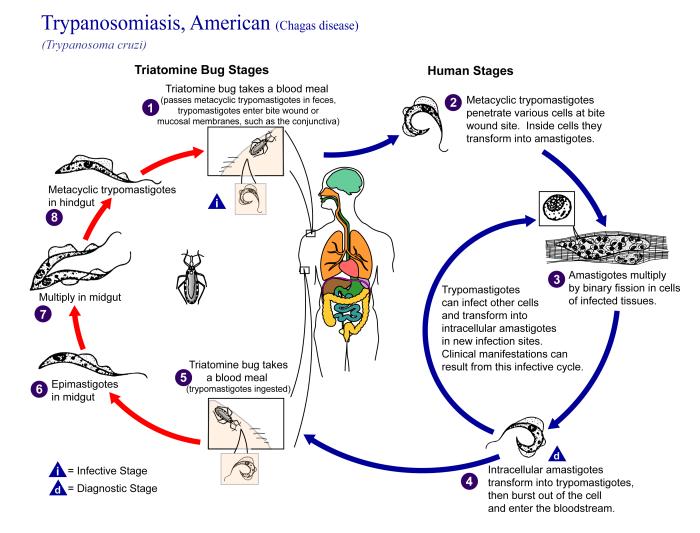

Editorial Note: Chagas disease is endemic in parts of Central and South America and Mexico, where an estimated 16-18 million persons are infected with T. cruzi (1). An estimated 25,000-100,000 Latin American immigrants living in the United States are infected with T. cruzi (2). In nature, T. cruzi is transmitted when mucous membranes or breaks in the skin are contaminated with the feces of infected triatomine bugs. Congenital infection and transmission by blood transfusion and organ transplantation also occur.

In humans, the acute phase of vectorborne T. cruzi infection lasts for weeks to months and typically is asymptomatic or associated with fever and other mild, nonspecific manifestations. However, life-threatening myocarditis or meningoencephalitis can occur during the acute phase, particularly in young children and immunocompromised persons. After years to decades of subclinical infection, 10%-30% of infected persons develop chronic Chagas disease, which is characterized by potentially lethal cardiomyoparhy or megasyndromes (i.e., megaesophagus and megacolon) (1). Even persons who remain asymptomatic probably are infected and infectious for life, with low levels of the parasite in blood and other tissues.

During the acute phase of infection, diagnosis involves detection of circulating organisms by microscopic examination of a fresh blood specimen or stained blood smear, hemoculture, or xenodiagnosis (1). Thereafter, diagnosis typically involves serologic testing because the level of parasitemia is too low to be detectable on blood smears. Hemoculture and xenodiagnosis can be positive, and polymerase chain reaction is a promising investigational technique for detecting low-level parasitemia (3). To decrease the risk for morbidity and mortality, infected persons should be treated as early in the course of infection as possible with either benznidazole (not available in the United States) or nifurtimox (available through the CDC Drug Service, telephone [404] 639-3670).

Transmission of T. cruzi infection by solid-organ transplantation (particularly renal transplants) has been reported in Latin America (4-9), where serologic screening of organ donors and recipients for antibody to T. cruzi is standard practice. In two instances, both recipients of a kidney from the same donor became infected with T. cruzi (8,9).

The cluster of three cases reported here represents the first recognized U.S. occurrence of T. cruzi infection through solid-organ transplantation. In the United States, no policies concerning the screening of potential organ donors for T. cruzi infection have been established. Although serologic tests for the diagnosis of T. cruzi infection are available in the United States, the tests vary in sensitivity and specificity. No test has been licensed in the United States for screening organ or blood donors.

CDC has notified the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS), which operates the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) under contract with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, about these cases of Chagas disease. CDC and the scientific committees of the OPTN/UNOS, which develops guidelines and policies for organ procurement, will consider whether to recommend screening of potential donors for T cruzi infection and, if so, which donors to screen, how to screen, and what to do if the screening tests are positive.

References

(1.) World Health Organization. Control of Chagas disease: report of a WHO expert committee. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 1991.

(2.) Kirchhoff LV, Gam AA, Gilliam FC. American trypanosomiasis (Chagas' disease) in Central American immigrants. Am J Med 1987;82:915-20.

(3.) Gomes ML, Galvao LMC, Macedo AM, Pena SDJ, Chiari E. Chagas' disease diagnosis: comparative analysis of parasitologic, molecular, and serologic methods. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1999;60:205-10.

(4.) Riatte A, Luna C, Sabatiello R, et al. Chagas' disease in patients with kidney transplants: 7 years of experience, 1989-1996. Clin Infect Dis 1999;29:561-7.

(5.) Vazquez MC, Riarte A, Pattin M, Lauricella M. Chagas' disease can be transmitted through kidney transplantation. Transplant Proc 1993;25:3259-60.

(6.) Vazquez MC, Sabbatiello R, Schiavelli R, et al. Chagas disease and transplantation. Transplant Proc 1996;28:3301-3.

(7.) Carvalho MFC, de Franco MF, Soares VA. Amastigotes forms of Trypanosoma cruzi detected in a renal allograft. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo 1997;39:223-6.

(8.) Ferraz AS, Figueiredo JFC. Transmission of Chagas' disease through transplanted kidney: occurrence of the acute form of the disease in two recipients from the same donor. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo 1993;35:461-3.

(9.) de Faria JB, Alves C. Transmission of Chagas' disease through cadaveric renal transplantation. Transplantation 1993;56: 1583-4.

COPYRIGHT 2002 U.S. Government Printing Office

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group