The Food and Drug Administration has announced a strategy to warn patients, their caregivers, and physicians about the possibility of an increased risk of suicidal thoughts and behavior (suicidality) in children and adolescents being treated with antidepressant medications.

The agency's definitive analysis of studies that compared the effects of nine antidepressants with the effects of an inactive substance (placebo) showed that those who received the antidepressants had an increased rate of suicidal thinking and behavior. No suicides were seen in the more than 4,000 patients in these studies. Acting FDA Commissioner Dr. Lester M. Crawford emphasized the critical importance of closely observing all patients, particularly children and adolescents who are just beginning antidepressant therapy.

In October 2004, the FDA announced a multi-pronged strategy designed to provide important new information to patients, families, and health care providers on the increased risk of suicidal thoughts and behavior in children and adolescents treated with antidepressant drugs. In designing this effort, the agency considered how best to minimize these risks while allowing use of the drugs in depressed children and adolescents who would benefit from them.

Based on the best scientific evidence and recommendations made at a joint meeting of the agency's psychopharmacologic and pediatric drugs advisory committees in September 2004, the FDA took the following actions to ensure that physicians and patients use appropriate care when prescribing and using antidepressants in children and adolescents:

* Issued a public health advisory warning about the increased risk of suicidal thinking and behavior in these patients.

* Directed manufacturers to add a "black box" warning to the health professional labeling of all antidepressant medications to describe the risks of treatment in these patients and to emphasize the need to monitor them closely when they begin using antidepressants and when doses are increased or decreased. The warning also lists the approved uses of the drug in children or, alternatively, indicates that there are no approved pediatric indications. The FDA's letters went to manufacturers of all antidepressants, new and old, because the data and analyses did not suggest that any antidepressants were free of the risk.

* Determined that a patient medication guide, called a MedGuide, must be given to patients with each prescription or refill to advise them of the risk and precautions that can be taken. The MedGuide currently is under development.

* Made plans to require that antidepressants be available only in "unit-of-use" packaging--a method of preparing a medication in an original container, sealed and labeled by the manufacturer, and containing sufficient medication for one normal course of therapy. Such unit-of-use packaging would include the MedGuide, ensuring that patients would receive a MedGuide with every prescription or refill.

Concerns about a possible risk of suicidality in children taking antidepressants emerged from an FDA analysis of a May 2003 report on pediatric studies of the antidepressant drug Paxil (paroxetine). The reported adverse experiences suggested that the drug might increase the risk of suicidality. The FDA subsequently asked the manufacturers of other antidepressants to submit suicidality data from their pediatric trials. The data on the other antidepressants studied in children, which focused on instances of self-harm as well as suicidal thinking, also suggested increased suicidality, but there was uncertainty among agency experts as to whether the behaviors reported represented actual suicide attempts or self-harm that was not suicide-related.

To help resolve this uncertainty, the reports were sent to the Columbia University medical school, which had developed specific expertise in assessing suicidality in children and adolescents. Although there was some impatience over the several months needed to complete this analysis, it was considered necessary because a number of the identified cases did not seem reasonably representative of suicidality. For example, one case that was classified as a suicide attempt was a child who had slapped herself in the face.

"It was important to get it right," says Thomas P. Laughren, M.D., a team leader in the psychopharmacology group of the FDA's Division of Neuropharmacological Drug Products. To conclude that the drugs increased suicidality if they did not, or to conclude that they did not increase suicidality if they did, would both be unfortunate errors with significant consequences, he says. Reaching a premature decision about the possibility of suicide risk could result either in the overly conservative use of antidepressants or in lack of availability. But a missed signal, he says, "would give us greater comfort in the use of these drugs than would be warranted."

Even before the analysis was completed, however, the FDA issued two public health advisories and conducted an advisory committee meeting in February 2004, indicating the nature of the agency's concerns.

"It now seems clear that the drugs do indeed increase the risk of suicidality in the trials, from about 2 percent to about 4 percent," says Robert Temple, M.D., director of the FDA's Office of Medical Policy. Agency experts continue to believe, however, that antidepressants may provide significant benefit for depressed pediatric patients when used appropriately. The new warning language does not prohibit the use of antidepressants in children and adolescents. Rather, it warns of the possible risk of suicidality and encourages prescribers to balance the risk with clinical need.

"We're not telling prescribers not to use these drugs," Laughren says. "But if they do, they have to watch these kids." The new warning language recognizes that psychiatric disorders can have significant consequences if not appropriately treated.

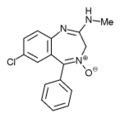

Currently, Prozac (fluoxetine) is the only medication approved to treat major depression in children and adolescents, while Prozac, Zoloft (sertraline), fluvoxamine maleate, and Anafranil (clomipramine) are approved for obsessive-compulsive disorder in pediatric patients. None of the other antidepressant drugs is approved for treatment of any psychiatric condition in children.

Antidepressant Awareness in Children

The drugs listed below, which are included in the general class of antidepressants, are the focus of new labeling language intended to make people aware of the increased risk of suicidal thoughts and actions in children taking them:

Anafranil (clomipramine HCI) Aventyl (nortriptyline HCI) Celexa (citalopram HBr) Cymbalta (duloxetine HCI) Desyrel (trazodone HCI) Effexor (venlafaxine HCI) Elavil (amitriptyline HCI) fluvoxamine maleate Lexapro (escitalopram oxalate) Limbitrol (chlordiazepoxide/ amitriptyline HCI) Ludiomil (maprotiline HCI) Marplan (isocarboxazid) Nardil (phenelzine sulfate) Norpramin (desipramine HCI) Pamelor (nortriptyline HCI) Parnate (tranylcypromine sulfate) Paxil (paroxetine HCI) Pexeva (paroxetine mesylate) Prozac (fluoxetine HCI) Remeron (mirtazapine) Sarafem (fluoxetine HCI) Serzone (nefazodone HCI) Sinequan (doxepin HCI) Surmontil (trimipramine) Symbyax (olanzapine/fluoxetine HCI) Tofranil (imipramine HCI) Tofranil-PM (imipramine pamoate) Triavil (perphenazine/amitriptyline HCI) Vivactil (protriptyline HCI) Wellbutrin (bupropion HCI) Zoloft (sertraline HCI) Zyban (bupropion HCI)

COPYRIGHT 2005 U.S. Government Printing Office

COPYRIGHT 2005 Gale Group