Abstract

We conducted a prospective, randomized, controlled, double-blind study of 33 patients to compare the efficacy and tolerabiliy of a new glycerin formulation of ototopical 0.3% ciprofloxacin with that of a conventional aqueous formulation of ciprofloxacin for the treatment of acute external otitis. Outcomes measures were resolution of discharge, swelling, pain, and redness and the incidence of adverse side effects. Patients were examined on three occasions: on the day of enrollment (visit 1), 48 to 72 hours later (visit 2), and 7 days after enrollment (visit 3). At visit 2, the patients in the glycerin group showed a significantly greater resolution of discharge. We observed the same pattern with respect to swelling, pain, and redness, which resolved more quickly in the glycerin group, although not significantly so. All patients were cured by visit 3, and the two treatments were equally well tolerated. On the basis of our findings, we conclude that the glycerin formulation of ototopical 0.3% ciprofloxacin appears to be at least as effective as the aqueous form in the treatment of acute external otitis--and in the case of otorrhea, more so.

Introduction

Drugs used topically in the ear are generally formulated into solutions or suspensions in a vehicle of anhydrous glycerin or propylene glycol. (1,2) The use of these viscous vehicles allows for maximum contact time between the medication and the tissues of the ear. In addition, these vehicles are hygroscopic--that is, they draw moisture from the tissues, thereby diminishing the moisture available to infecting microorganisms and reducing inflammation. (2)

Acute external otitis (AEO) is the most common infection of the external auditory canal. This painful condition is the consequence of a secondary infection of macerated skin and subcutaneous tissues of the external auditory canal. The most common clinical manifestation of AEO is pain when the pinna is touched or pulled or when pressure is placed on the tragus. Other signs include drainage from the canal, swelling, redness, and pruritus. (3) Exposure of the ear to water can predispose patients to this condition.

Management of AEO with ototopical agents is common practice among otolaryngologists. (4) Several combinations of ototopical preparations are available to treat external and middle ear infections. The major components of these products are antiinfectives such as polymyxin B, neomycin, gentamicin, and chloramphenicol in a nonaqueous hygroscopic vehicle, to which a corticosteroid is frequently added. Some of these agents are recognized as ototoxic, and there is convincing evidence that they can cause sensorineural hearing loss in animals. Because Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, gram-negative bacilli, and anaerobic organisms alone or in combination are the predominant sources of infection, it is important to rely on medications that have a broad spectrum of activity. (5)

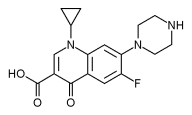

Ciprofloxacin was the first fluoroquinolone to become available as an ototopical preparation. No evidence of ototoxicity after topical application of ciprofloxacin in 1.55-to 7.5-mg/ml solutions has been seen in either animal or clinical studies. (4) Ciprofloxacin has been shown to be effective against the pathogens that are commonly associated with ear infections, including P aeruginosa and methicillin-resistant S aureus. Ciprofloxacin has not been detected in plasma following ototopical applications, suggesting that systemic absorption is negligible. This fact allows it to be used in children younger than 18 years, for whom oral ciprofloxacin is approved only for complicated urinary tract infection and pyelonephritis. (4,6,7) Therefore, topical antibiotic formulations such as ciprofloxacin eardrops that have an appropriate antimicrobial spectrum and that confer no risk of ototoxicity are valuable tools for the therapeutic management of ear infections.

Because the solubility of ciprofloxacin is low in water, glycerin, and propylene glycol, (8) it has been formulated as an aqueous solution of its hydrochloride (HCl) salt. Therefore, the pH of this formulation is approximately 4. There are several commercially available ciprofloxacin otic formulations that have a concentration of 0.2 to 0.3%. Ciprofloxacin is also combined with either hydrocortisone or dexamethasone. Current compositions are made up of the active drug in an aqueous vehicle, a pH-regulating agent, a thickening agent, and an antimicrobial preservative.

To overcome the drawbacks associated with ciprofloxacin's low solubility, we developed a new ototopical formulation--0.3% ciprofloxacin in a glycerin vehicle--by increasing the apparent solubility in this medium through aluminum complexation. (9) The glycerin replaces the water, which has been associated with trauma and epithelial damage in ear tissues, and it avoids an acidic pH, which is known to strongly reduce ciprofloxacin's antimicrobial activity. (10) Another advantage of using glycerin is that additional antimicrobial preservation is not necessary because this function is fulfilled by the glycerin itself when its concentration is greater than 20%. (2)

Because systemic absorption of topical products is negligible and because ciprofloxacin does not produce an acute pharmacologic effect that could be monitored, the appropriate way to assess the efficacy and tolerability of the new ciprofloxacin glycerin product, according to the literature, (11) is a controlled clinical trial.

Our objective was to compare the therapeutic efficacy and tolerability of the 0.3% ciprofloxacin glycerin solution with that of the standard 0.3% ciprofloxacin aqueous solution. The study hypothesis was that while both formulations would be equivalent in terms of eradicating pathogens, they might have different effects in terms of alleviating discharge, swelling, pain, and redness.

Patients and methods

Patients. Inclusion criteria were (1) the presence of AOE manifested as drainage, swelling, pain, and/or erythema in the external ear canal, (2) bacteriologic confirmation of infection, and (3) an ability to follow investigators' instructions. Exclusion criteria were (1) the presence of an allergy or contraindication to quinolones, (2) the need to start an incompatible treatment during the study period, (3) the presence of a chronic illness that required long-term pharmacologic therapy, and (4) participation in another clinical trial during the previous 15 days.

Formulations. To ensure the integrity of the preparations and to enable a double-blind design, both the aqueous and glycerin formulations were prepared under aseptic conditions at the Departamento de Farmacia at the Facultad de Ciencias Quimicas of the Universidad National de Cordoba in Argentina. The solution containing the 0.3% ciprofloxacin in a sterile glycerin vehicle was aseptically prepared according to the patent application in transit. (12) The 0.3% ciprofloxacin aqueous solution was prepared by aseptically assembling its components according to the stated formula on the label of a commercially available product (table 1 ). The final solution was filtered through a sterile-sterilizing 0.2-[micro] Millipore filter. Both formulations were packed in 10-mi polyvinyl chloride droppers labeled with randomly generated numbers. (13) The droppers were given to physicians who were blinded to the vehicle in each.

Study design. This prospective, randomized, controlled, comparative, double-blind trial was designed according to guidelines established by Argentina's Administracion Nacional de Medicamentos, Alimentos y Tecnologia Medica. (14) The study was conducted between Jan. 18 and May 30, 2003, by otolaryngologists at the Clinica Privada de la Familia in Cordoba, Argentina; the study protocol was approved by that center's Ethical Review Committee. Participants received detailed information on the study, including a patient information sheet, and written consent was obtained from all patients or their parents before enrollment.

Patients were randomly allocated to receive either the aqueous or glycerin solution at a dosage of 3 drops twice daily for 7 days. (15) All patients were taught how to correctly apply their drops. They were advised to warm the dropper with their hands until the drops achieved room temperature in order to avoid the vertigo that can occur when a cold drop is instilled into the ear. They were instructed to apply the medication while they were in a supine position with the target ear facing the ceiling. They were to introduce the drops into the external meatus and to massage the tragus for 30 to 60 seconds.

Patients were examined on three occasions: on the day of enrollment (visit 1), 48 to 72 hours later (visit 2), and 7 days after the beginning of treatment (visit 3). The clinical endpoint was a complete cessation of AEO symptoms.

At each visit, the physicians recorded the degree of ear drainage, swelling, pain, and redness as well as any side effects of the drug (e.g., pruritus, pain, or burning):

Drainage. Discharge from the canal was classified as either purulent or mucous. Any change from purulent to mucous was considered an improvement--as, of course, was complete resolution of otorrhea.

Swelling. Swelling was diagnosed by otomicroscopy and classified according to how far it extended through the external ear canal as either slight (one-third of the canal), moderate (two-thirds), or intense (the entire canal).

Pain. Pain was recorded as either existent or nonexistent according to the patient's reaction when the tragus was pressed.

Redness. Otomicroscopy was also used to classify redness as either existent or nonexistent.

Side effects. Patients were asked about any discomfort or unpleasant sensations they might have experienced when they instilled their drops.

Pathogens. At visit 1, the investigators obtained an ear swab for culture, inoculated it into appropriate agar media, and identified the pathogens after incubation by standard microbiologic techniques. Sensitivity to ciprofloxacin was tested by the disk method. (4) Bacteriologic tests were also carried out.

Statistical analysis. After treatment was completed, the findings were reviewed by the study monitor for final review, data cleaning, and final statistical analysis. The chi-squared test was used to calculate and compare the percentages of responses in both groups.

Results

A total of 37 patients were initially enrolled in the study and allocated to a study treatment. However, findings in 4 patients were excluded from the final analysis because they committed protocol violations with respect to keeping scheduled appointments. Therefore, the efficacy analysis was based on the findings in 33 patients--15 in the aqueous group and 18 in the glycerin group.

Visit 1. All patients had unilateral disease.

Discharge. At visit 1, otorrhea was present in 29 of the 33 patients (87.9%)--in 12 of the 15 aqueous patients and in 17 of the 18 glycerin patients (table 2).

Swelling. Swelling was present in 31 patients (93.9%); 1 patient in each group did not present with swelling.

Pain. All 33 patients presented with pain.

Redness. Erythema was present in 32 patients (97.0%); the lone exception was a patient in the aqueous group.

Pathogens. Cultures were positive in all 33 patients; 7 patients had more than one pathogen (table 2). Of the 40 isolates, 17 were identified as S aureus (42.5%), 15 as P aeruginosa (37.5%), 4 as Hemophilus species (10%), 3 as Proteus species (7.5%), and 1 as beta-hemolytic streptococci (2.5%). Dual pathogens were seen in 3 patients in the aqueous group and 4 in the glycerin group. In all 7 cases of multiple isolates, S aureus was one of the infecting microorganisms; S aureus occurred with Hemophilus species in 3 patients, with Proteus species in 3 patients, and with P aeruginosa in 1 patient. Susceptibility tests showed that 100% of these pathogens were sensitive to ciprofloxacin.

Visit 2. All 33 patients were fully compliant with their treatment regimen. At visit 2, clinical cure was achieved in 2 of the 15 patients in the aqueous group (13.3%) and in 4 of the 18 in the glycerin group (22.2%).

Discharge. Improvement was seen in 10 of the 12 aqueous patients (83.3%) and in all 17 of the glycerin patients--a statistically significant difference (table 3). The 2 patients who did not improve showed no change in discharge status.

Swelling. All but 1 patient experienced a reduction in swelling (table 4). The exception was a patient in the aqueous group whose edema actually became worse (from moderate to intense).

Pain. Pain disappeared in 13 of the 15 aqueous patients (86.7%) and in 16 of the 18 (88.9%) glycerin patients. One patient in the aqueous group whose pain persisted required medication with intravenous hydrocortisone at visit 2.

Redness. Rates of erythema resolution were low in both groups. Redness disappeared in only 3 of 14 aqueous patients (21.4%) and in 5 of 18 glycerin patients (27.8%).

Side effects. The two treatments were equally well tolerated. One patient in each group reported some pruritus after the treatment period ended. No adverse event was reported during treatment.

Visit 3. As expected, 100% of the patients in both groups had been cured by visit 3.

Discussion

Topical antibiotics have been shown to be more effective than systemic antibiotics in resolving otorrhea and in eradicating bacteria. (16-18) Moreover, combining a topical and systemic antibiotic is no more effective than using a topical antibiotic alone. (6) Ototopical quinolones have been shown to be more effective than nonquinolones. (17) Ototopical treatments are very desirable for use in children, considering the high incidence of ear infections in the pediatric population. No oral antibiotics that are effective against P aeruginosa have been approved for use in children. (5) The potential for ototoxicity with the use of aminoglycoside otic drops has limited their use in children. Ototoxicity has been investigated as a possible adverse effect of ototopical ciprofloxacin therapy in several animal and clinical studies, but no such evidence has been found. (4)

A preservative-free, ototopical 0.2% ciprofloxacin aqueous formula has been developed and supplied in single-dose containers in order to obviate the need for antimicrobial preservatives. Although this represents an achievement, the solution is still aqueous and it has an acidic pH, which is an unfavorable factor with respect to ciprofloxacin activity. In addition, some topical adverse effects related to the large volume of water instilled (0.5 ml) with this formulation have been reported. (4)

An alternative to otic drops are powders. Topical antibiotics have been applied in powder form by insufflation. Antibiotic powders deliver a high concentration of antibiotic without contributing to moisturization of the canal. (18) However, treatment with powder forms is not effective in patients who have a severely edematous external auditory canal.

As we expected, our study showed that both treatments were very successful in achieving clinical responses at visit 3, proving again that ciprofloxacin is effective against the pathogens that are commonly associated with ear infections.

The difference between the two groups with respect to ear drainage was statistically significant at a 90% confidence interval. This difference might have been the result of the favorable effect provided by the glycerin vehicle (e.g., the longer contact time between the medication and the target site and the high degree of hygroscopicity). We observed the same pattern with respect to swelling, pain, and redness, which was less in the glycerin group, although not significantly so. The slower rate of recovery in the aqueous group might have been secondary to the presence of water, which can cause the canal to become erythematous and macerated.

On the basis of the clinical and bacteriologic data obtained in this study, we conclude that the glycerin form of 0.3% ciprofloxacin appears to be at least as effective as the aqueous form in the treatment of AEO--and in the ease of discharge, more so. We believe that the glycerin medium minimizes moisture in the external ear canal and perhaps even helps dry the mucoid debris. Therefore, we believe that the glycerin formulation represents a more rational design and a good pharmaceutical alternative to the aqueous agent. We intend to conduct further studies to test the glycerin formulation for other indications.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank pharmacists Carolina Romanuk and Andrea Breda for their valuable help during the study.

References

(1.) Ansel HC, Popovich NG. Pharmaceutical Dosage Forms and Drug Delivery Systems. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lea and Febiger, 1990.

(2.) Wade A, Weller PJ. Handbook of Pharmaceutical Excipients. 2nd ed. Washington: American Pharmaceutical Association, London: Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain, 1994:204-6.

(3.) Hughes E, Lee JH. Otitis externa. Pediatr Rev 2001;22:191-7.

(4.) Miro N. Controlled multicenter study on chronic suppurative otitis media treated with topical applications of ciprofloxacin 0.2% solution in single-dose containers or combination of polymyxin B, neomycin, and hydrocortisone suspension. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2000; 123:617-23.

(5.) Jang CH, Park SY. Emergence of ciprofloxacin-resistant pseudomonas in pediatric otitis media. In J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2003;67:313-16.

(6.) Grandis J, Yu V. Treatment of infections of the ears, nose, throat and nasal carriage. In: Hooper DC. Wolfson JS, eds. Quinolone Antimicrobial Agents. 2nd ed. Washington: American Society for Microbiology, 1993:363-9.

(7.) Clinical Pharmacology. Gold Standard Multimedia. cp.gsm.com (accessed on July 19, 2004).

(8.) Fallati C. Ahumada A, Manzo R. El perfil de solubilidad de la Ciprofloxacina en funcion del pH. Acta Farmaceutica Bonaerense 1994; 13:73-7.

(9.) Manzo R, Mazzieri M, Olivera M. Preparacion de complejos en estado solido de clorhidratos de antimicrobianos fluoroquiolonicos (AMFQs) con aluminio. Argentinean Patent Application P960104386. Nacional Institute of Intellectual Property. 1996.

(10.) Alovero FL, Olivera ME, Manzu RH. In vitro pharmacodynamic properties of a fluoroquinolone pharmaceutical derivative: Hydrochloride of ciprofloxacin-aluminum complex. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2003:21:446-51.

(11.) Mayer M. Bioavailability of transdermal and topical dosage forms. In: Welling PG, Tse FL, Dighe SV, eds. Pharmaceutical Bioequivalence. New York: Dekker, 1991:169-221.

(12.) Olivera M, Manzo R. Desarrollo y optimization de una formulacion otica de Ciprofloxacino utilizando glicerina como vehiculo. Argentinean patent application in transit, 2002.

(13.) Mendenhall W. Wackerly D, Scheaffer R, eds. Estadistica Matematica con Aplicaciones. 2nd ed. Grupo Editorial Iberoamerica, SA de CV, Mexico DF, 1994.

(14.) Administration Nacional de Medicamentos. Alimentos y Tecnologia Medica. www.anmat.gov.ar (accessed on July 19, 2004).

(15) Morden NE, Berke EM. Topical fluoroquinolones for eye and ear. Am Fam Physician 2000;62:1870-6.

(16.) Esposito S. D'Errico G, Montanato C. Topical and oral treatment of chronic otitis media with ciprofloxacin. A preliminary study. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1990; 116:557-9.

(17.) Morpeth JF, Bent JP, Watson T. A comparison of cortisporin and ciprofloxacin otic drops as prophylaxis against post-tympanostomy otorrhea. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngo1 2001;61:99-104.

(18.) Goldenberg D, Golz A, Netzer A, Joachims HZ. The use of otic powder in the treatment of acute external otitis. Am J Otolaryngol 2002;23:142-7.

From the Departamento de Farmacia, Facultad de Ciencias Quimicas, Universidad Nacional de Cordoba, Argentina (Dr. Olivera and Dr. Manzo), and the Clinica Privada de la Familia, Cordoba (Dr. Bistoni, Mr. Anun, and Dr. Salinas).

Reprint requests: Dr. Ruben H. Manzo, Departamento de Farmacia, Facultad de Ciencias Quimicas, Universidad National de Cordoba, Ciudad Universitaria (5000), Cordoba, Argentina. Phone: 54-351-433-4163, ext. 112; fax: 54-351-433-4127; e-mail: rubmanzo@dqo.fcq.unc.edu.ar

Financial support for this study was provided by a Ramon-Carrillo Onativia grant, National Health Ministry, Argentina.

COPYRIGHT 2004 Medquest Communications, LLC

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group