Objective: To determine the efficacy of the antidepressant citalopram in the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Method: The cases of two Persian Gulf War veterans are described to illustrate the effects of citalopram in treating their PTSD symptoms. Results: In these two clinical case studies, citalopram led to remission of some of the PTSD symptoms. Conclusion: More controlled studies are warranted to further prove the efficacy of citalopram as an agent of choice for the treatment of PTSD.

Introduction

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which has specific diagnostic criteria described in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-M, has an estimated prevalence of 1% in the general population.2 In combat soldiers and especially those who have been wounded, the incidence of PTSD has been estimated to be as high as 40%.3

During and after the Persian Gulf War in 1991, military personnel deployed in Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and Iraq who encountered war-zone trauma experienced a clinical level of psychosocial impairment4; it is estimated that 10% of Gulf War veterans meet the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria of PTSD.5 This statistic illustrates the clinical need for intervention and treatment of this major psychiatric disorder.6

The comprehensive treatment of PTSD requires an integration of psychotherapy, psychosocial intervention, and psychopharmacological therapy.7-9 Because of the high incidence of comorbid psychiatric conditions in PTSD, including major depression, generalized anxiety disorder, substance use disorder, and personality disorders, it is often not clear if psychopharmacological treatment initially induces improvement in these comorbid disorders or if treatment specifically improves the symptoms of PSD.2,10,11

There is emerging evidence from placebo-controlled studies as well as clinical case studies that psychopharmacologic therapy can provide symptomatic relief of the anxiety, insomnia, anger, and depression associated with PTSD even in the absence of comorbid psychiatric conditions.7 Antidepressants, including tricyclic agents, monamine oxidase inhibitors, and the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), benzodiazepines, buspirone, mood stabilizers, beta-blockers, a-adrenergic agonists, and antipsychotic agents have all been studied in clinical trials and used in the treatment of PTSD.7-9

Although the SSRI sertraline was approved in 1999 as a specific pharmacological agent for the treatment of PTSD, we report two patients with PTSD symptoms related to their Gulf War experiences who improved with the SSRI citalopram. Neither patient had any other comorbid psychiatric condition, so the improvement in their PTSD symptoms is assumed to be related to the efficacy of citalopram. Two case reports only, however, must be viewed with caution, and to further prove this assumption, additional clinical studies and controlled research trials are warranted.

Case Reports

Case A

Mr. A is a 22-year-old single male Egyptian Gulf War veteran who meets the DSM-fV diagnostic criteria of PTSD. He suffered from repetitive flashbacks for 2 years after being terrified of being shot in the head point-blank by an Iraqi soldier. Although he was not shot or injured, Mr. A continued to exhibit symptoms of anxiety, hypervigilance, inability to initiate or maintain sleep, and recurrent nightmares. He also tended to isolate himself and felt detached from his family and friends. Mr. A's brother, who was a graduate student at the Department of Psychology at Al-Azhar University Faculty of Medicine, firmly believed that these symptoms were clinical manifestations of a severe and chronic case of PTSD, because Mr. A did not abuse any illicit drugs, alcohol, or tobacco and did not have any previous history of psychiatric disorder. In addition, Mr. A had a negative family history of psychiatric and substance abuse disorders. Mr. A's brother did not approve of any treatment with medications that have addictive potential or medications that are lethal in case of an overdose; however, he did urge his brother to be treated with the SSRI fluoxetine. After a 3-week trial of fluoxetine 20 mg daily, Mr. A did not notice any significant change in his condition; he could not, however, tolerate the side effects of increased restlessness and nausea related to fluoxetine, and he subsequently discontinued it. During that same time interval, citalopram became available and Mr. A agreed to use it. Treatment began with citalopram 20 mg every morning; this apparently caused excessive sleepiness, however, so the medication was given at bedtime. Initially, no beneficial effect was noticed, but toward the end of the third week of treatment, Mr. A noticed a marked improvement in his sleep and did not have the symptoms of daytime anxiety and hypervigilance. Although he continued to move restlessly and constantly in his sleep, he did not recall having the recurrent Gulf War-associated nightmares. Mr. A continued to have repetitive flashbacks of being shot in the head, although the feelings of terror that usually accompanied these flashbacks subsided. At the time of writing this report, Mr. A. had been taking the same 20-mg dose of citalopram for 3 months. He had not developed any side effects to it, his social isolation subsided, and he was engaged and getting ready to be married.

Case B

Mr. B is a 36-year-old British army soldier who was subjected to friendly fire during the Gulf War. He was severely wounded in the chest, both hands, and upper abdomen. He was still suffering from chronic and severe PTSD 5 years after that traumatic experience. Although Mr. B was physically restored to a perfect state of general health, his ongoing PTSD symptoms included reexperiencing of his traumatic injuries, seeing himself bleeding and losing consciousness, smelling his blood gushing, and feeling as if he were being shot and wounded. He also experienced significant anxiety, worry, irritability, and restlessness, like he was "crawling out of his skin." Whenever he read or watched news related to the Persian Gulf region, he would suddenly experience profound fear with symptoms of autonomic hyperactivity, including tachycardia, lightheadedness, and shortness of breath. Mr. B did not have any of these symptoms before his service in the Gulf War, he did not abuse alcohol, illicit drugs, or tobacco, and he had no other psychiatric disorders. He has been divorced for 3 years; the symptoms of PTSD had disrupted his intimate marital relationship. He did not want to be treated with any psychotropic medication for fear of being stigmatized and labeled "a crazy person." During a recent visit to the United States, he met an American veteran who was suffering from hepatitis C and secondary depression that was being treated with the antidepressant sertraline. Some of the American veteran's depressive symptoms were also accompanied by mixed anxiety features such as profound fear, autonomic hyperactivity, and shortness of breath. The American veteran related to Mr. B that since he began treatment with sertraline, he noticed a remarkable improvement in both his anxiety and depressive symptoms. Upon return to England, Mr. B requested that his general practitioner prescribe him sertraline; unfortunately, this drug was not available in this particular national health clinic's formulary. The general practitioner suggested a trial of citalopram, to which Mr. B agreed. Treatment began with a 20-mg daily dose of citalopram. After a 5-week course of treatment, no changes in symptoms occurred. The citalopram dose was increased to 40 mg daily. After 7 weeks of treatment, Mr. B's symptoms of profound fear, tachycardia, lightheadedness, irritability, and restlessness subsided. Gradually over the course of 4 months, he started to feel comfortable reading the news, and even if there were disturbing accounts about recent deployments of British troops to the Persian Gulf region, he was able to perform his daily activities without recurrence of anxiety. Although he continued to have recurrent intrusive thoughts about being injured, Mr. B has been able to cope with these events without psychological distress. At present, no side effects have developed to the 40-mg daily dose of citalopram, and Mr. B wants to be maintained on it.

Discussion

Since the Vietnam War era, PTSD has been increasingly diagnosed and identified as a chronic and severe psychiatric disorder.23 The treatment of PTSD requires both a biopsychosocial and a multidimensional approach, and psychopharmacological intervention is an integral component of combined management including individual, group, and family therapy.3 Although more scientific studies are needed to identify pharmacological agents that are specifically designed to treat PTSD, clinically designed controlled trials of various medications have found certain classes of agents to be useful in some patients during the course of their illness.7,8, 10 The best clinical outcomes in symptom reduction seem to be achieved with the antidepressants, including the tricyclic agents, monamine oxidase inhibitors, and SSRIs.7,10,12 Mood stabilizers such as lithium, carbamazepine, and valproic acid have shown good efficacy in reducing aggressive tendencies, reducing intrusive recollections of traumatic events, and amelioration of sleep disturbances and flashbacks, especially in combat veterans.7,12 Benzodiazepines have not been specifically tested in MSD given the risks associated with their potential for addiction and behavioral disinhibition; however, they can be useful for the short-term treatment of the acute exacerbation of chronic PTSD symptoms.11,12 Buspirone, an anxiolytic agent, has been reported to be effective in few patients with severe PTSD.9,10 Other agents, including the beta-blocker propranolol and the alpha-adrenergic agonist clonidine, have been used to alleviate symptoms of hypervigilance and hyperarousal.10,11 Antipsychotic medication has a limited indication in treating brief psychotic episodes that are usually associated with agitation, aggression, and loss of impulse control.7,8 Studies suggest that the SSRIs, such as fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, sertraline, and paroxetine, when given to patients with combat-related PTSD for 3 or more weeks, produce significant improvement in the symptoms of avoidance, reexperiencing of traumatic events, and hyperarousal.9,12,13 This improvement was independent of comorbid panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and major depressive disorder. 13.14 Given the role of serotonin in depressive and anxiety disorders,13,15 the SSRIs seem to have a specific effect on ameliorating some of the most disabling PTSD symptoms even if full remission of the disorder is not achieved. 15

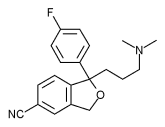

To our knowledge this is the first report addressing the effects of citalopram for the symptomatic treatment of MSD. Citalopram was discovered in 1972 and first used in Denmark in 1989; it is one of the most prescribed SSRIs in eight European countries.16 The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved it in 1998 for the treatment of depression. In some other countries, citalopram is also approved for the treatment of panic disorder. Although it is not the most potent SSRI, citalopram is highly selective, with minimal affinity for dopamine, norepinephrine, histamine, gamma-aminobutyric acid, acetylcholine, or benzodiazepines. 16,17 The side effect profile of citalopram is comparable to that of other SSRIs and may include nausea, dry mouth, somnolence, insomnia, increased sweating, tremor, diarrhea, and sexual dysfunction.17 Citalopram is considered to be nonactivating; it is minimally sedating depending on the daily dosage. The half-life of citalopram is 30 hours, and it can be administered once a day.16,17 The initial dose is 20 mg daily; doses of more than 40 mg are not usually needed. If dose increases are deemed to be clinically necessary, it is recommended that they occur in 20-mg increases at a weekly interval.17

Conclusion

Because SSRIs are now usually considered the first line of treatment in uncomplicated depressive disorders, obsessive compulsive disorder, panic disorder, and an expanding range of behavioral conditions, they can also be considered as optional agents for the treatment of MD. Although the efficacy of citalopram in treating these Gulf War veterans was achieved without the occurrence of any adverse effects, these results cannot be used as proof to consider this agent "the medication of choice" for PTSD. Such a conclusion could only be reached through prospective, double-blind, controlled trials with a large sample of patients.

The treatment of PTSD is often a long and arduous clinical task, with frequent episodes of remissions and exacerbations of symptoms. Although psychotherapy is an integral component of comprehensive treatment, psychopharmacological agents, especially antidepressants, play an important role in alleviating the disabling symptoms of PTSD. These case reports reflect the clinical experience that was associated with the pharmacological treatment of some PTSD symptoms with the antidepressant citalopram.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Kellie Condon and David Dupuis for their clinical support and Emma Nichols for her administrative assistance.

References

1. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994.

2. Helzer J, Robins L, McEvoy L: Post-traumatic stress disorder in the general population: findings of the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Survey. N Engl J Med 1987;317:1630-4.

3. Pitman R, Altman B, Macklin M: Prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder in wounded Vietnam veterans. Am J Psychiatry 1989; 146: 667-9.

4. Southwick S, Morgan CR, Darnell A, et al: Trauma-related symptoms in veterans of Operation Desert Storm: a 2-year follow-up. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152: 1150-5. 5. Wolfe J, Proctor S: The Persian Gulf War. PTSD Research Quarterly 1996: 7: 1-7. 6. Farhood L. Chaaya M, Madi-Skaff J: Patterns of mental illness from psychiatrists'

caseloads in different wartime periods. Arab J Psychiatry 1997; 8: 87-98.

7. Sutherland S, Davidson J: Pharmacotherapy for post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1994; 17: 409-23.

8. Friedman M: Toward rational pharmacotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: an interim report. Am J Psychiatry 1988; 145: 281-5.

9. Duffy J, Malloy P: Efficacy of buspirone in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder: an open trial. Ann Clin Psychiatry 1994: 6: 33-7.

10. van der Kolb B: Psychopharmacology: psychopharmacological issues in posttraumatic stress disorder. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1983: 34: 683-4, 691.

11. Khouzam H, Boutros N: B-blockers in psychiatry: a clinical review for primary care. Hospital Physicians 1994; 30(9): 24-30.

12. Davidson J: Drug therapy of post-traumatic stress disorder. Br J Psychiatry 1992; 160: 309-14.

13. Shay J: Fluoxetine reduces explosiveness and elevates mood of Vietnam combat vets with PTSD. J Trauma Stress 1992: 5: 97-101,

14. Solomon S, Gerrity E, Muff A: Efficacy of treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder: an empirical review. JAMA 1992; 268: 633-8.

15. Katz R, Lott M, Arbus P, et al: Pharmacotherapy of post-traumatic stress disorder with a novel psychotropic. Anxiety 1995; 1: 169-74.

16. Hyttel J: Pharmacological characterization of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1994: 9(Suppl 1): 19-26.

17. Milne R Goa K: Citalopram: a review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties, and therapeutic potential in depressive illness. Drugs 1991; 41: 450-77.

Guarantor: Hani Raoul Khouzam, MD MPH FAPA

Contributors: Hani Raoul Khouzam, MD MPH FAPA*; Fayez El-Gabalawi, MD^; Nancy J. Donnelly, MS ARNP CS^^

*Staff Psychiatrist and Medical Director, Chemical Dependency Treatment Program, Veterans Administration Central California Health Care System, Fresno, CA; Adjunct Associate Professor of Psychiatry, Dartmouth Medical School, Lebanon, NH; and Clinical Instructor in Medicine, Harvard Medical School. Boston, MA.

^Director Inpatient Adolescent Unit, Belmont Center, Albert Einstein Medical Center, Philadelphia, PA; Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Psychiatry, Thomas Jefferson University Hospital and Temple University Hospital, Philadelphia, PA; and Associate Training Director, Division of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA.

^^Psychiatric Clinical Nurse Practitioner Specialist, VA Medical Center, Manchester, NH. This manuscript was received for review in February 2001. The revised manuscript was accepted for publication in June 2001.

Copyright Association of Military Surgeons of the United States Oct 2001

Provided by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights Reserved