Thirty years ago, hormones were all the rage -- literally. In 1970, a prominent doctor and political adviser named Edgar Berman infuriated feminists when he made an outrageous statement: that women's "raging hormonal influences" should preclude them from holding positions of power.

Today, most people, and thankfully doctors, know better. In general, our bodies regulate these natural hormonal fluxes with precision and finesse. But because our female brains are wired to be highly responsive to sex hormones, sometimes these vital hormones exert negative effects, dampening our moods, making us irritable, or sparking a case of the blues or, in rare cases, a serious mental disorder.

According to Deborah Sichel, M.D., a psychiatrist specializing in female mood disorders at the Hestia Institute in Wellesley, Mass., and the co-author of Women's Moods (William Morrow, 1999), estrogen acts as a natural "upper" and mood stabilizer in the brain, while progesterone is more of a "downer." The interplay between these mood-altering hormones and brain chemicals such as serotonin -- which rises and falls with estrogen and must remain at certain levels to prevent depression and anxiety -- helps to maintain our emotional balance. But kinks in this interaction appear to be at least partially responsible for the fact that women are twice as likely as men to develop depression and anxiety disorders, especially during times of major hormonal change. Here are four of those times:

1. Before your period

The week or so before the menstrual period is often characterized by symptoms of premenstrual syndrome (PMS). "Up to 85 percent of women experience at least one symptom of PMS," says Joseph T. Martorano, M.D., a New York psychiatrist and author of Unmasking PMS (M. Evans & Co., 1993). These include a spectrum of moods -- sadness, irritability, anxiety, confusion -- that can range from mild to severe, along with physical symptoms that may include breast tenderness, abdominal bloating and headache. Between 3 and 7 percent of PMS sufferers have symptoms that are so incapacitating that they interfere with daily life. PMS usually lasts two to five days, but may plague some unlucky women for up to 21 days out of each 28-day cycle.

Unfortunately, there are no tests to confirm that you have PMS, and relatively few treatments for it are available. This dearth exists because doctors are not exactly sure what causes the syndrome. Currently, the most-discussed medical theory is that PMS sufferers are extra responsive to hormonal fluctuations.

Over the course of the menstrual cycle, estrogen and progesterone levels increase and decrease predictably. At the start of each 28-day cycle (defined as the first day of your period), estrogen and progesterone levels are low. Then, on about day seven, estrogen starts to rise. It peaks around day 13 or 14 (just before ovulation takes place), and then suddenly drops and stays low for several days. Estrogen levels spike again between days 21 and 24 before taking a final slope downward. This latter fall in estrogen is accompanied by a surge in progesterone levels around days 19-27.

"Women with PMS have normal amounts of estrogen and progesterone, but it seems that their brains may be sensitive to changes in the levels of these hormones," says Nada Stotland, M.D., professor of psychiatry and obstetrics and gynecology at Rush Medical College in Chicago. Martorano concurs, suggesting that progesterone might be to blame, while Sichel and Others implicate estrogen or both hormones as the culprits.

2. During and after pregnancy

Pregnancy and the birth of a child are among the happiest times of a woman's life -- or so most people believe. But a new British study of 9,000 women suggests that 14 percent experience prenatal depression -- although most cases escape detection by OB-GYNs or even by the women themselves. Instead, women suffer silently, too stigmatized to acknowledge that they are feeling low at a time when society says they should be ecstatic.

After giving birth, when hormone levels suddenly plummet, up to 80 percent of women might experience several days of feeling down (the typical "baby blues"), characterized by crying, anxiety, irritability and difficulty sleeping. These symptoms usually begin three to four days after delivery and continue for about 12 days. In most cases, they resolve on their own.

Hormones again appear to be a key precipitator since pregnancy is characterized by huge hormonal shifts as estrogen and progesterone levels rise dramatically, along with the stress hormone cortisol. These surges, which are necessary to support the developing fetus may overwhelm a woman's brain chemistry, potentially trigering swift, varying and irrational moods, Sichel says. In rare instance, hormone changes during pregnancy can even kick off seriod mental illnesses, such as a major depression or post partum psychosis.

However, approximately 10 percent of new mothers who have never suffered from depression (excluding postpartum depression) before will have major or minor depressive symptoms -- such as despondency, guilt, worry, bizarre or suicidal thoughts and an inability to cope -- after giving birth. This type of mood disorder typically strikes immediately after the birth and may last for several months or even years if it remains undiagnosed or is left untreated. "Women who have had severe PMS, postpartum depression and major depression before are at particularly high risk," reports Peter Schmidt, M.D., an investigator with the National Institute of Mental Health. Such women may have been suffering from undiagnosed depression throughout the duration of their pregnancies.

Another British study shows that women are at a greater risk for psychosis during the three months after they've given birth than at any other time of life. Sichel says that one in 1,000-3,000 women may experience hallucinations, delusions, agitation and confusion.

Frightening news stories, like that of Andrea Yates, the Houston-area mother who confessed to drowning her five young children last year, and who may also suffer from schizophrenia, suggest that in rare cases postpartum psychosis may even drive new mothers to violence against their children.

3. Stressful times

Like falling estrogen levels, stress can alter your brain chemistry and deplete serotonin. A body that's under stress reacts by releasing hormones that will whelp it respond to a perceived physical or emotional challenge, says Sarah Berga, M.D., professor and director of the Division of Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine. The production of these stress hormones, such as cortisol, puts the body and brain on high alert, but it stops when the stress abates.

But what if stress doesn't subside? In the familiar case of chronic, unrelieved stress, the body begins to react to minor triggers, such as the changes in estrogen and progesterone that occur premenstrually. The body then finds it increasingly difficult to discontinue the production of stress chemicals and to relax. This state of hyperalertness, or what Sichel calls "brain strain," can eventually disrupt the brain's functioning and lead to mood alterations, as well as physical symptoms such as headaches, stomach woes and fatigue.

"The impact of estrogen and progesterone fluctuations on your stress level depends on both the state of the brain when the fluctuations occur and the extent of the changes," Berga says. If you are already stressed out when a hormonal surge or dip occurs, you are more likely to experience a mood effect. "A major change in your hormone levels, such as during pregnancy and after delivery, can serve as a stressor in and of itself, magnifying the effects of other stressors in your life," she adds. "Likewise, other stresses in your life can magnify the effects of hormone changes."

4. Medications

Among the medications that can trigger mood changes: oral contraceptives. Study results from the Kinsey Institute for Research in Sex, Gender and Reproduction published in the journal Contraception found that the birth control pill can have significant adverse effects on mood in 40 percent of women, increasing the likelihood of early discontinuation. Yet some women never make the connection between mood changes and oral contraceptives. "Women may not notice their negative mood because they have been on the pill for so long, they don't know what their mood would be like if they were off hormones," says Sichel.

On the other hand, oral contraceptives are widely prescribed for the treatment of PMS, even though few data support their effectiveness, according to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Still, some medical experts, such as Sichel, believe women who are sensitive to the changing levels of hormones across their natural cycle are helped by stable doses of the pill.

More problematic is the injectable Depo-Provera, which with each quarterly treatment reduces estrogen levels to below normal and gives you a giant dose of progesterone, Berga says. The five-year contraceptive implant Norplant also can affect mood, although hormone levels tend to return to normal soon after the rods are surgically removed.

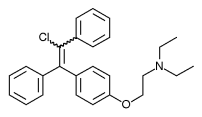

Likewise, fertility drugs (such as Pergonal, Clomid and Metrodin) that raise estrogen to 10 times the normal level to induce ovulation are notorious, she says, for causing mood swings, depression, irritability and hostility. (While estrogen is an "upper" when released naturally during the menstrual cycle, at high doses it has the opposite effect, Sichel says.)

Your best defense

The best defense against negative mood changes is to be aware that they can occur, and to be on the lookout for warning signs of an impending crash. "Learn about your body and its vulnerabilities," Stotland advises. Determine if you are sensitive to estrogen and/or progesterone by keeping track of mood changes and checking to see if they relate to predictable hormonal fluctuations, such as those brought about by your menstrual cycle, or events, such as pregnancy or starting or stopping the pill.

And be sure to tell your OB-GYN if you have a history of PMS, depression, anxiety disorders or postpartum mood changes - or if anyone in your family has suffered from these problems, since there are genetic links, Finally, don't be afraid to seek treatment. "These are all real biochemical disorders that can and should be treated," Sichel says. "You don't have to suffer in silence or in shame."

RELATED ARTICLE: How to Stay on an Even Keel

Follow these steps to keep your hormones in balance - and your hormone-induced mood swings to a minimum.

* Exercise regularly. Physical activity prompts the body to produce those feel-good neurotransmitters called endorphins and boosts serotonin levels to improve mood naturally. Research shows that exercise - both aerobic and strength training - can reduce and prevent depression and improve PMS symptoms. currently, most experts recommend getting 30 minutes of moderate-intensity activity most days of the week.

* Eat well. Many women eat too few calories and follow diets that are deficient in vitamins, minerals and protein. Others don't eat often enough, so their blood sugar level is unsteady. Either way, when your brain is in a fuel-deprived state, it is more sensitive to stress, says Sarah Berga, M.D., of the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine. Eating five to six small meals a day that contain a good mix of carbohydrates - which can raise serotonin levels - and protein may smooth out rough emotional edges.

* Take calcium supplements. Research by Susan Thys-Jacobs, M.D., of St. Luke's-Roosevelt Hospital in New York city, found that taking 1,200 milligrams of calcium carbonate daily reduces PMS symptoms by 48 percent. There is also some evidence that taking 200-400 mg of magnesium may be helpful. Less proof exists to verify that vitamin [B.sub.6] and herbal remedies such as evening primrose oil work for PMS, but they may be worth a try.

* Seek treatment. The good news about hormonally related mood disorders -depression, anxiety and severe PMS - is that they are treatable once they are diagnosed. The drugs most commonly prescribed for these disorders are the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), such as Prozac (renamed Sarafem for severe PMS sufferers), Zoloft, Paxil and Effexor, which make more serotonin available in the brain.

"These drugs work for about two-thirds of women with severe PMS - and within a week or two," says Peter Schmidt, M.D., of the National Institute of Mental Health, "vs. the four to six weeks they take to relieve depression." To reduce potential side effects and ward off the development of a tolerance to these drugs, some physicians prescribe them for use during only the last two weeks of the menstrual cycle.

Studies show that SSRIs can even be used during and after pregnancy (and while breast-feeding) if a woman is severely depressed or suicidal. There is also limited evidence to suggest that oral progesterone may help to quell certain PMS mood symptoms, such as worrying.

Nancy Monson is a health, nutrition and fitness writer in Brookline, Mass.

COPYRIGHT 2002 Weider Publications

COPYRIGHT 2002 Gale Group