Fifty years ago this week, Philip Hench showed that "compound E" (cortisone) was capable of reversing the inflammation of rheumatoid arthritis. This discovery resulted from 19 years of imaginative and deductive observation together, perhaps, with that element of serendipity which seems to characterise many fundamental discoveries.

It all started in 1929 when Hench noted a clinical remission in one of his patients who suffered an intercurrent episode of jaundice. Convinced that this was no coincidence he decided to devote himself to the discovery of the nature of "antirheumatic substance X" in remissions associated with jaundice, and later, with pregnancy. His clinical researches involved giving many metabolites related to liver disease and subsequently, female hormones related to pregnancy. They were uniformly unsuccessful.

Because remissions associated with jaundice occurred as frequently in women as in men, Hench concluded that factor X, if a hormone, must be present in both sexes. This led him to consider the adrenal cortex. He also noted that the gross fatigue seen in patients with rheumatoid arthritis bore some resemblance to the allergy which characterises Addison's disease.

By happy chance, his colleague and friend at the Mayo Clinic, Edward Kendall, had, in 1929, switched his research studies to the separation and characterisation of the many unidentified hormones of the adrenal cortex. This work was laborious and the yields extremely small. Nevertheless, Hench persuaded Kendall to allow him to use any extracts he could spare for therapeutic trials. Compounds labelled "A/D" proved ineffective, but compound "E," first administered on 21 September 1948, produced dramatic results.

Thus we learnt of long term bedridden disabled people attempting to dance. One patient insisted on taking several baths on the same day to compensate for the years during which such a luxury had been denied her.

Hench tried hard to restrict premature publicity outside the confines of the Mayo clinic until the full implications and complications of his discovery had been studied. However, a medical correspondent from the New York Times gained entry to a private meeting of Mayo Clinic alumni and published sensational stories and pictures in the lay press. This forced Hench's hand and he eventually announced his discovery to the Seventh International Congress of Rheumatology in May 1949.

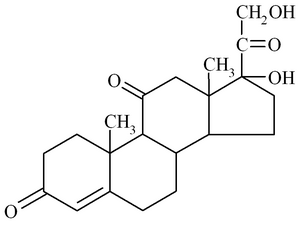

Hench was a renowned Anglophile, and following the congress he invited several of his close British friends to visit the Mayo Clinic so that they could observe the therapeutic potency of cortisone for themselves. They were impressed, and on returning to Britain organised a motley team of clinicians and biochemists who decided to investigate the clinical significance of cortisone in rheumatoid arthritis. I was fortunate to be appointed as their research registrar. On Hench's introduction, they had obtained a promise from Merck Sharpe & Dohme that they would receive the first batch of cortisone which became available for export. There followed a tantalising delay of more than a year, during which time the production of cortisone in commercial quantities defeated biochemist and pharmaceutical companies alike. During this period all that we could do was to perfect our methods of clinical evaluation, while confirming that steroid analogues which did not contain the 17-hydroxy and 11-keto radicals were ineffective. It was precisely these radicals which proved so difficult to synthesise. In those days the only known starting point of semisynthes!s was from the bile of sheep and cattle. This seemed likely to limit supplies permanently.

In the United States a black market developed which had serious medical and social repercussions. Patients who had experienced great relief of their symptoms were not prepared to relapse when supplies ran out. They became totally dependent on the drug. Overdosage led to devastating side effects, and the ever escalating cost of maintaining their supplies resulted all too often in financial destitution. Such patients had no alternative but to seek relief by registering as guinea pigs to research groups such as the one at the Bellevue Hospital in New York which I joined in 1952.

Eventually, in 1954, under the joint aegis of the Nuffield Foundation and the Medical Research Council, a British trial was organised in six centres in which the benefits of cortisone were studied in 61 patients with rheumatoid arthritis in a crossover trial against aspirin. The published results startlingly concluded that there was no significant difference between the two groups (BMJ 1954;i:1223-7).

Philip Hench was deeply offended by these conclusions especially as they were signed by many colleagues whom he had numbered among his greatest friends. Indeed he was heard to refer to some of the signatories as traitors and he refused any further association with them.

I felt that the crossover nature of the trial and some of the methods of evaluation gave rise to an unrealistic conclusion and I imprudently wrote a letter (BMJ 1954;i: 1376). My letter drew an angry reply from Sir Austin Bradford-Hill, the distinguished medical statistician who had designed the trial protocol (BMJ 1954;i:1437). I met him many years later and he graciously agreed that some of my comments were justified in the light of subsequent events.

A few weeks later, there was a totally unexpected repercussion in the form of a letter to me from Philip Hench, asking me whether I thought that the atmosphere in Britain was propitious for him to accept an invitation to come and address a BMA meeting. He was not prepared to come if there was any risk of being heckled.

From this improbable beginning, a close friendship developed between this great man and my family. In fact he was in our house the day before the birth of my daughter and, at his insistence, she bears the female version of his first name. It was only with some difficulty that we resisted the idea that she should be christened Cortisona.

Philip Hench had a charismatic and generous personality. He was a man of diverse and enthusiastic interests outside medicine. His sensitivity on the subject of his seminal contribution to medicine was unfortunate, and it undoubtedly marred the pleasure he should have derived from his fame and from the Nobel prize for medicine in 1950. It was especially unfortunate in view of his original intention to present his discovery as an investigative tool rather than as a therapeutic breakthrough.

The clinical usefulness of cortisone in rheumatology remains controversial 50 years after the event, but without doubt its discovery transformed the specialty from its Cinderella status of the BC (before cortisone) era. Its significance in general medicine remains beyond dispute.

COPYRIGHT 1998 British Medical Association

COPYRIGHT 2000 Gale Group