For the past 40 years, oral contraceptives (OCs) have been prescribed on a regimen of 21 days of active pills and 7 days of placebo. This schedule was designed to induce a withdrawal bleed and reassure women that they were not pregnant; however, it also meant that women experienced side effects related to menstruation and to OC use. In numerous studies, side effects have been shown to reduce compliance. (1-5)

Over the years, the dosage of estrogen contained in OCs has been decreased. New progestins with improved side-effect profiles have also been introduced, making OC use more tolerable for many women while offering additional benefits that include treatment of premenstrual syndrome (PMS) and premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD).

Recently, clinicians also have altered the standard 21/7 regimen, reducing the pill-free interval to eliminate or reduce monthly bleeding as well as the symptoms associated with estrogen withdrawal. These new paradigms also offer the opportunity to improve overall patient health and well-being and reduce menstruation-related gynecologic disorders. They also have raised the question: Is a monthly bleed necessary or desirable? Notably, no health benefits are associated with monthly withdrawal bleeding associated with the 7-day hormone-free interval of OCs. Indeed, until recently, most women did not have frequent monthly bleeds: Menarche generally occurred between ages 16 and 18. Childbearing began at about age 19.5.

Breastfeeding typically lasted for 2 years. Today, women have earlier menarche, postpone pregnancy, limit the number of pregnancies, and breastfeed for a short time. As a result, contemporary women typically experience a greater number of menstrual cycles than did their ancestors. (6)

Contemporary women also often experience menstrual disorders, including menorrhagia, irregular bleeding, dysmenorrhea, PMS, and menstrual migraine headaches. During the perimenopausal transition, they also experience the bleeding irregularities and other symptoms that result from erratic ovulation and hormonal fluctuations. (7-12)

Conditions treated with OCs The persistent ovulation experienced by many women is assetiated with conditions often treated by OC use, * including:

Abnormal or excessive bleeding patterns. The effect of OCs on abnormal bleeding patterns was evaluated in a multicenter, randomized, double-blind study of 201 women with dysfunctional uterine bleeding. The study reported significant (P<.001) improvement with treatment (ethinyl estradiol [EE]/triphasic norgestimate) compared with placebo. (8)

Anemia. The duration of menstrual bleeding and iron stores were evaluated in a study of 268 OC users and nonusers. Use of OCs lcd to significantly shorter duration of menstrual bleeding and mean serum ferritin levels of 40 mg/L. (13)

Endometriosis. Oral contraceptives have long been used as first-line therapy for endometriosis: the progesterone effect results in atrophy of the endometrium and endometriotic tissue. This effect is also associated with reduced likelihood of new lesions.

Functional ovarian cysts. In a study enrolling 428 women aged 14 to 45, ovarian cysts were revealed in 29 women. Prevalence was lower for women using OCs (relative risk = 0.22; confidence interval, 0.13-0.39) than for women using no contraception or nonhormonal intrauterine contraceptive devices. (14)

Ovarian cancer. Reduction in ovarian and endometrial cancer risk in women who use OCs has been noted in pivotal clinical trials conducted over the past 3 decades. (15-17) Protection gradually increases within 1 year of initiation of OC use and persists for years after discontinuation. (18)

Additionally, OCs provide beneficial effects on menstruation, including reduction in dysmenorrhea (19,20) improved cycle control, and the emergence of predictable bleeding patterns. (8,11,21)

MENSTRUAL SYMPTOMS AND OC USE

For women using OCs, menstrual symptoms have been shown to be most severe during the traditional 7-day, hormone-free interval. For this reason, clinicians have sought to shorten this interval and reduce symptom severity. * Patterns of hormone withdrawal symptoms in new and long-term OC users were evaluated in a 2000 study by Sulak et al. Of 262 women enrolled in the study, 193 had used OCs for 12 months or longer, 43 were prior users, and 26 had no prior OC use. Participants recorded their symptoms in daily diaries. Symptoms included pelvic pain, headaches. breast tenderness, bloating/swelling, and use of pain medications. Among current OC users, symptoms occurred more frequently during hormone-free intervals than during the 3 active-pill weeks (Table 11. New OC users experienced similar symptom patterns after the first cycle, particularly with respect to pelvic pain (Figure 1) and bloating/swelling (Figure 2). (22)

[FIGURES 1-2 OMITTED]

The initiation of some symptoms during the last week of active-pill administration is not surprising: Investigations have shown that some women actually cycle while taking OCs on the traditional 21/7 regimen. Follicle-stimulating hormone levels begin to increase on day 3 to 4 of the pill-free interval, allowing follicular recruitment and estradiol production. Administration of active pills results in follicular degeneration: estrogen withdrawal begins before the next hormone-free interval. In a study comparing 58 women on 21/7 and 24/4 regimens, ovulation was inhibited in all of the cycles in women on the 24/4 regimen and in 74 of 75 cycles of women on the 21/7 regimen. No unruptured follicles were seen in the 24/4 group, whereas 6 were noted in the 21/7 group. (23) Shortening the hormone-free interval from 7 days to 4 days provided greater ovarian suppression in this study.

CHANGING THE STANDARD 21/7 REGIMEN: CURRENT/FUTURE TRENDS

Shortening the standard pill-free interval provides greater ovarian suppression and decreases the incidence and severity of hormone withdrawal symptoms.

Shortening the pill-free interval and/or extending the number of active pills improves symptom control and improves contraception. In one study, 292 patients on OC regimens containing EE (30 to 35 [micro]g) and a variety of progestins (norethindrone, levonorgestrel, norgestimate, or desogestrel) were given the option of extending their active pills. Many cited symptoms associated with the hormone-free week as a key reason for doing so. The typical pill-free interval was decreased from 7 days to a median of 5 days: 46% of participants used an interval of less than 7 days. Participants also extended active treatment of an average of 12 weeks of active pills. Of the 92% who attempted an extended regimen, 47% were still on the extended regimen 5 years laters. (24)

An extended-regimen OC has recently been approved. While this regimen extends the time between the pill-free intervals, it is associated with an increased risk of breakthrough bleeding, primarily limited to spotting in the first 2 cycles (each cycle consisting of 84 days of active-pill administration). Nevertheless, the option of using an OC with a shortened hormone-free interval does allow for flexibility in meeting the needs and desires of individual patients. Specifically, the extended-regimen OCs reduce, troublesome menstrual symptoms, thereby improving quality of life (QOL) for women. (25)

NEW PROGESTINS AND IMPROVED SIDE-EFFECT PROFILES

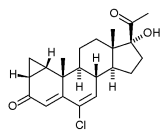

While progestins are often referred to by generation, these categories relate primarily to their introduction to the market as derivatives of 19-nortestosterone; therefore, they have a mild androgenic effect. (26-29) The newer progestins were developed to maintain the benefits of low-dose OCs while improving their side-effect profile. Oral contraceptives containing desogestrel and norgestimate, among the so-called "third generation" OCs, provide cycle control comparable to that of earlier low-dose OCs containing levonorgestrel. These formulations have a negligible effect on carbohydrate metabolism and a lower level of androgenicity than formulations containing levonorgestrel. (30)

The newest progestin on the US market, drospirenone (DRSP), is not derived from 19-nortestosterone. Rather, it is an analogue of spironolactone and, as a result, exhibits antiandrogenic and antimineralocorticoid activity.

Drospirenone shows effects similar to those of endogenous progesterone: potent progestogenic, antiandrogenic, and antimineralocorticoid activities, and no androgenic activity. (31-34) Table 2 shows the biologic activity of progestins.

The OC containing DRSP also provides cycle control comparable to that of other low-dose OCs and has a small impact on carbohydrate metabolism, equal to that of a low-dose OC containing desogestrel.

PROPERTIES OF PROGESTINS AND POTENTIAL BENEFITS

The properties of various progestins offer additional opportunities for the clinician to tailor the choice of an OC to the individual needs of the patient.

Improved acne

While acne generally constitutes a nuisance condition, patient awareness of potential benefits to skin may help improve compliance. Oral contraceptives that contain estrogen should improve acne. (30) Currently, 1 EE/norgestimate formulation and 1 EE/norethindrone acetate formulation have approval of the US Food and Drug Administration as treatments for acne. (35-36) In other countries, an EE/cyproterone acetate (CPA) (an antiandrogenic progestin) formulation is approved for acne.

The EE/DRSP OC has been shown to be as effective as EE/CPA in treating acne. (37) * In a multi-center, single-blind, randomized study of 125 women, 82 were prescribed DRSP, 3 mg, and EE, 30 [micro], while 43 received CPA, 2 mg, and EE, 35 [micro]g. After 9 treatment cycles, the median total acne lesion count was reduced by 62.5% in the EE/DRSP group and 58.8% in the EE/CPA group. (38) A study accepted for publication in Cutis compared EE/DRSP with EE/norgestimate. The EE/DRSP regimen showed a greater effect in reducing total lesion count (-3.3% 195% CI, -6.5 to -0.1 ; P = .021) and an increased therapeutic effect on facial acne (+3.6% 195% CI, 0.8 to 6.3, P = .0061) by cycle 6. (39)

Improvement of bloating symptoms

Ethinyl estradiol causes an increase in serum aldosterone levels, resulting in sodium and water retention, bloating, and breast tenderness, Drospirenone--the only progestin not derived from 19-nortestosterone--blocks aldosterone at its receptor. As a result, it has diureticlike effects: sodium and water excretion is increased, and potassium may be retained. Thus, the weight gain associated with water retention, common with 19-nortestosterone derivatives, does not occur. (40)

Weight change was monitored in a 26-cycle open-label efficacy study of 887 women who were randomized to DRSP, 3 mg, plus EE, 30 [micro]g, or to desogestrel, 150 [micro]g, plus EE, 30 [micro]g. The EE/desogestrel regimen was associated with a small weight gain over cycles 6 to 26, with a mean range of +0.02 kg to +0.89 kg. The mean weight change of women in the group using DRSP/EE was slightly below the baseline weight for 24 of 26 cycles (range -0.01 kg to -0.15 kg). (36)

PMS AND PMDD: TREATMENT WITH OCs

Approximately 70% to 90% of reproductive-age women report some symptoms associated with their menstrual period. Of this group, 20% to 40% believe they have PMS. About 3% to 8% of reproductive-age women have symptoms that are severe enough to qualify as PMDD. (41)

In 2000, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists published diagnostic criteria for PMS. One or more of the following affective and/or somatic symptoms must occur during the 5 days before menses in 3 consecutive prior menstrual cycles: depression, angry outbursts, irritability, anxiety, confusion, social withdrawal, breast tenderness, abdominal bloating, headache, and swelling of extremities. Symptoms must impair some aspect of life. (42)

While data regarding the use of OCs to treat menstruation-related mood disorders and/or improve QOL are inconsistent, mounting evidence suggests that OCs containing DRSP may provide benefits. Additionally, 1 OC containing a 19-nortestosterone-derived progestin has been associated with improved QOL. However, data do not support the use of OCs containing progestins derived from 19-nortestosterone to treat mood disorders. (43-46)

Improvement in QOL with OC use

Overall QOL scores have been improved in women receiving OCs containing desogestrel and EE. The Quality of Life and Enjoyment questionnaire was used to assess 614 first-time OC users. Over 4 months, 56% of women noted improved QOL, 18% had no change, and 26% experienced deterioration. (47) A multicenter observational study enrolling 3679 first-time OC users also revealed statistically significant (P<.O01) improvements from baseline in physical health, mood, work/school, household activities, social relationships, family relationships, leisure-time activities, daily life, sex life, living situation, vision, general well-being, and overall satisfaction. (48)

Improvement in PMS/PMDD with OC use

More specific improvements to PMDD and PMS symptoms have been associated with DRSP. Several small, randomized, double-blind placebo trials have shown the efficacy of spironolactone, in reducing premenstrual and mood symptoms. (49-51) As noted, DRSP is an analogue of spironolactone.

Trials also have evaluated DRSP efficacy in treating PMS and PMDD and improving QOL.

In an open-label study lasting 13 cycles, 326 women were evaluated using the Menstrual Distress Questionnaire to record symptoms associated with each phase of the cycle. Effects were recorded at the end of cycle 6. The women who were prescribed EE/DRSP had statistically significant decreases from baseline in negative affect and water retention in all menstrual phases (Figure 3). Increased appetite was significantly lower in the premenstrual and menstrual phases of the cycle. (52)

[FIGURE 3 OMITTED]

A more detailed evaluation of data from this study compared women who were new users (n = 150) with those who bad switched to EE/DRSP from another OC (n = 176). It showed statistically significant symptom improvement within both groups; DRSP minimized negative affect, water retention, and increased appetite in women who switched to EE/DRSP from another OC and in new OC users (Figure 4). (34)

[FIGURE 4 OMITTED]

A randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial enrolled 82 participants with PMDD (as defined by the American Psychiatric Association criteria) who received either EE/DRSP or placebo. The primary study endpoint was a change from baseline symptoms reported during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle using the Calendar of Premenstrual Experiences scale. Secondary endpoints were the, Beck Depression Inventory and Profile of Mood States. Women in the active treatment group demonstrated a 14% improvement of symptoms, which indicated a consistent trend in the, reduction of symptoms although the improvement was not statistically significant. Differences between the groups reached statistical significance (P = .027) for appetite, acne, and food cravings (Figure 5). (53)

[FIGURE 5 OMITTED]

Other studies show a benefit of EE/DRSP on premenstrual symptoms. A survey of 858 women who had recently initiated use of an OC containing DRSP revealed that, after 2 cycles, the women experienced significantly reduced premenstrual symptoms (P = .000) and an improved sense of well-being (P<.05) compared with baseline. Additionally, in the health-related QOL assessment, statistically significant improvements in the Mental Component Summary (P = .000) were observed; improvements in the Physical Component Summary did not reach statistical significance. (54)

In 2003, a 5-cycle open study of EE/DRSP enrolled 335 women to evaluate fluid-related symptoms and general well-being. Participants experienced a significantly reduced incidence and severity of abdominal bloating (P<.O01) and breast tension (P<.O01) associated with the menstrual cycle. A beneficial effect also was seen in general well-being (P<.0001), as measured by the Psychological General Well-Being Index. The improvement was shown at cycle 3 and maintained at cycle 6. (55)

CONCLUSION

Oral contraceptives offer an excellent strategy to avoid pregnancy and manage or prevent health problems for reproductive-age women. Long-term OC use can also reduce the risk for future gynecologic and other health problems. New regimens that shorten the traditional 7-day hormone-free interval offer opportunities to improve contraceptive efficacy and reduce side effects associated with hormone withdrawal while maintaining the reassurance of monthly bleeding. Other strategies include extending the cycle of active-pill administration beyond the traditional 21 days.

REFERENCES

(1.) Rosenberg MR, Waugh MS, Burnhill MS. Compliance, counseling and satisfaction with oral contraceptives. Fam Plann Perspect. 1998;30:89-92,104.

(2.) Gaudet LM, Kives S, Hahn PM, et al. What women believe about oral contraceptives and effect of counseling. Contraception. 2004;59:31-35.

(3.) Picardo CM, Nichols M, Edelman A, et al. Women's knowledge and sources of information on the risks and benefits of oral contraception. J Am Med Womens Assoc. 2003;58:112-115.

(4.) Rosenberg MI, Waugh MS. Oral contraceptive discontinuation: a prospective evaluation of frequency and reasons. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:557-582.

(5.) Aubeny E, Buhler M, Colau JC, et al. Oral contraception: patterns of non-compliance. The Coraliance study. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2002;7:155-151.

(6.) Eaton SB, Pike MC, Short RV, et al. Women's reproductive cancers in evolutionary context. Quart Rev Biol. 1994;69:353-353.

(7.) Casper RF, Dodin S, Rerd RL. The effect of 20 mg of ethinyl estradiol 1 mg NET (Minestrin) on vaginal bleeding pattern, hot flashes, and quality of life in symptomatic perimenopausal women. Menopause. 1997;4:139-147.

(8.) Davis A, Godwin A, Lippman J, et al. Triphasic norgestimate-ethinyl estradiol for treating dysfunctional uterine bleeding. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96:913-920.

(9.) Ross RK, Pike MC, Vessey ME et al. Risk factors for uterine fibroids: reduced risk associated with oral contraceptives [published correction appears in Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1986;293:1027]. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1986;293:359-362.

(10.) Parazzini F, Negri E, La Vecchia C, et al. Oral contraceptive use and risk of uterine fibroids. Obstet Gynecol. 1992;79:430-433.

(11.) Larsson G, Milsom I, Lindstedt G, Rybo G. The influence of a low-dose combined oral contraceptive on menstrual blood loss and iron status. Contraception. 1992;46:327-334.

(12.) Hankinson SE, Colditz GA, Hunter DJ, et al. A quantitative assessment of oral contraceptive use and risk of ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 1992;80:708-714.

(13.) Milman N, Clausen J, Byg KE. Iron status in 268 Danish women aged 18-30 years: influence of menstruation, contraceptive method, and iron supplementation. Ann Hematol. 1998;77:13-19.

(14.) Christensen JT, Boldsen JL, Westergaard JG. Functional ovarian cysts in premenopausal and gynecologically healthy women. Contraception. 2002;66:153-157.

(15.) Ness RB, Grisso JA, Klapper J, et al. Risk of ovarian cancer in relation to estrogen and progestin dose and use characteristics of oral contraceptives. SHARE Study Group. Steroid Hormones and Reproductions. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152:233-241.

(16.) Modan B, Hartge P, Hirsh-Yechezkel G, et al. Parity, oral contraceptives, and the risk of ovarian cancer among carriers and noncarriers of a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. National Israel Ovarian Cancer Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:235-240.

(17.) Narod SA, Risch H, Moslehi R, et al. Oral contraceptives and the risk of hereditary ovarian cancer. Hereditary Ovarian Cancer Clinical Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:424-428.

(18.) The reduction in risk of ovarian cancer associated with oral-contraceptive use. The Cancer and Steroid Hormone Study of the Centers for Disease Control and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:650-555.

(19.) Milsom I, Sundell G, Andersch B. The influence of different combined oral contraceptives on the prevalence and severity of dysmenorrhea. Contraception. 1990;42:497-506.

(20.) Callejo J, Diaz J, Ruiz A, Garcia RM. Effect of a low-dose oral contraceptive containing 20 microg ethinylestradiol and 150 microg desogestrel on dysmenorrhea. Contraception. 2003;58:183-188.

(21.) Sulak E Lippman J, Siu C, et al. Clinical comparison of triphasic norgestimate/35 micrograms ethinyl estradiol and monophasic norethindrone acetate/20 micrograms ethinyl estradiol: cycle control, lipid effects, and user satisfaction. Contraception. 1999;59:161-166.

(22.) Sulak P J, Scow RD, Preece C, et al. Hormone withdrawal symptoms in oral contraceptive users. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95:251-265.

(23.) Sullivan H, Furniss H, Spona J, et al. Effect of 21-day and 24-day oral contraceptive containing gestodene (60 microg) and ethinyl estradiol (15 microg) on ovarian activity. Fertil Steril. 1999;72:115-120.

(24.) Sulak P J, Kuehl T J, Ortiz M, et al. Acceptance of altering the standard 21-day/7-day oral contraceptive regimen to delay menses and reduce hormone withdrawal symptoms. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:1142-1146.

(25.) Sulak PJ, Carl J, Gopalakrishnan I, et al. Outcomes of extended oral contraceptive regimens with a shortened hormone-free interval to manage breakthrough bleeding. Contraception. In press.

(26.) Stancyk FZ, Roy S. Metabolism of levonorgestrel, norethindrone, and structurally related contraceptive steroids. Contraception. 1990;42:67-96.

(27.) Stancyzk FZ. Pharmacokinetics of the new progestins and influence of gestodene and desogestrel on ethinyl estradiol metabolism. Contraception. 1997;55:273-282.

(28.) Fotherby K. Pharmacokinetics and metabolism of progestins in humans. In: Goldzieher JW, Fotherby K, eds. Pharmacology of the Contraceptive Steroids. New York, NY: Raven Press; 1994:99-126.

(29.) Petitti DB. Combination estrogen-progestin oral contraceptives. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1443-1450.

(30.) Speroff L, Darney PD. Oral contraception. In: A Clinical Guide for Contraception. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001:121-137.

(31.) Gaspard U, Scheen A, Endrikat J, et al. A randomized study over 13 cycles to assess the influence of oral contraceptives containing ethinylestradiol combined with drospirenone or desogestrel on carbohydrate metabolism. Contraception. 2003;67:423-429.

(32.) Oelkers W, Foidart JM, Dombrovicz N, et al. Effects of a new oral contraceptive containing an antimineralocorticoid progestogen, drospirenone, on the renin-aldosterone system, body weight, blood pressure, glucose tolerance, and lipid metabolism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995;80:1816-1821.

(33.) Foidart JM, Wuttke W, Bouw GM, et al. A comparative investigation of contraceptive reliability, cycle control and tolerance of two monophasic oral contraceptives containing either drospirenone or desogestrel. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2000;5:124-134.

(34.) Brown C, Ling E Wan J. A new monophasic oral contraceptive containing drospirenone. Effect on premenstrual symptoms. J Reprod Med. 2002;47:14-22.

(35.) Ortho Tri-Cyclen (norgestimate/ethinyl estradiol) [prescribing information]. Raritan, NJ: Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceutical, Inc.; rev 2001.

(36.) Estrostep (norethindrone acetate/ethinyl estradiol tablets). Physicians' Desk Reference, 57th ed. Montvale, NJ: Thomson PDR; 2003:2535-2544.

(37.) Fugere P, Percival-Smith RK, Lussier-Cacan S, et al. Cyproterone acetate/ethinyl estradiol in the treatment of acne. A comparative dose-response study of the estrogen component. Contraception. 1990;42:225-234.

(38.) van Vloten WA, van Haselen CW, van Zuuren E, et al. The effect of 2 combined oral contraceptives containing either drospirenone or cyproterone acetate on acne and seborrhea. Cutis. 2002;69:2-15.

(39.) Thorneycroft IH, Gollnick H, Schellschmidt I. Superiority of a combined contraceptive containing drospirenone to a triphasic preparation containing norgestimate in acne treatment. Cutis. In press.

(40.) Krattenmacher R. Drospirenone: pharmacology and pharmacokinetics of a unique progestogen. Contraception. 2000;62:29-38.

(41.) Ginsburg KA, Dinsay R. Premenstrual syndrome, in: Ransom SB, ed. Practical Strategies in Obstetrics and Gynecology. Philadelphia, Pa: WB Saunders; 2000:684-694.

(42.) Premenstrual syndrome. ACOG Practice Bulletin, No. 15. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95(4).

(43.) Rapkin A. A review of treatment of premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Psycho-neuroendocrinology. 2003;28(suppl 3):39-53.

(44.) Graham CA, Sherwin BB. A prospective treatment study of premenstrual symptoms using a triphasic oral contraceptive. J Psychosom Res. 1992;36:257-266.

(45.) Graham CA, Sherwin BB. The relationship between retrospective premenstrual symptom reporting and present oral contraceptive use. J Psychosom Res. 1987;31:45-53.

(46.) Bancroft J, Rennie D. The impact of oral contraceptive use on perimenstrual mood, clumsiness, food cravings, and other symptoms. J Psychosom Res. 1993;37:195-202.

(47.) Egarter C, Topcuoglu MA, Imhof M, et al. Low dose oral contraceptives and quality of life. Contraception. 1999;59:287-291.

(48.) Ernst U, Baumgartner L, Bauer U, et al. Improvement of quality of life in women using a low-dose desogestrel-containing contraceptive: results of an observational clinical evaluation. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2002;7:238-243.

(49.) Wang M, Hammarback S, Lindhe BA, et al. Treatment of premenstrual syndrome by spironolactone: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1995;74:803-809.

(50.) O'Brien PM, Craven D, Selby C, et al. Treatment of premenstrual syndrome by spironolactone. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1979;86:142-147.

(51.) Vellacott ID, Shroff NE, Pearce MY, et al. A double-blind placebo-controlled evaluation of spironolactone in the premenstrual syndrome. Curr Med Res Opin. 1987:10:450-456.

(52.) Parsey KS, Pang A. An open-label, multicenter study to evaluate Yasmin, a low-dose combination oral contraceptive containing drospirenone, a new progestogen. Contraception. 2000;61:105-111.

(53.) Freeman EW, Kroll R, Rapkin A, et al. Evaluation of a unique oral contraceptive in the treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. PMS/PMDD Research Group. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2001;10:561-569.

(54.) Borenstein J, Yu HT, Wade S, et al. Effect of an oral contraceptive containing ethinyl estradiol and drospirenone on premenstrual symptomatology and health-related quality of life. J Reprod Med. 2003;48:79-85.

(55.) Apter D, Borsos A, Baumgartner W, et al. Effect of an oral contraceptive containing drospirenone and ethinylestradiol on general well-being and fluid-related symptoms. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2003;8:37-51.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

Clinicians should counsel patients regarding the potential health benefits and side-effect profile of available OC regimens.

In light of the relation between discontinuation and side effects, clinicians should consider new formulations that reduce common side effects, such as bloating, and are useful in treating PMS and PMDD. New treatment paradigms offer strategies to reduce side effects associated with the hormone-free interval or to reduce frequency of scheduled bleeding. These include reducing the number of pill-free days or extending the menstrual cycle.

COPYRIGHT 2004 Dowden Health Media, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group