More, Now, Again: A Memoir of Addiction, by Elizabeth Wurtzel (Simon & Schuster, 333 pp., $25)

Elizabeth Wurtzel isn't exactly a household name, but she was briefly a phenomenon in the early-mid 1990s when her memoir Prozac Nation was published. At the time, judging from the obsessive media attention the drug was receiving, you might have thought every person in America was taking Prozac, an antidepressant that was supposed to peel away layers of bad false personality -- anxiety, sadness, compulsion -- to reveal the true happy you underneath. Wurtzel's book wasn't really about her Prozac prescription, though; its real theme was the way divorce damages children, who grow up to be damaged adults, as the author did following her own parents' divorce. Still, the fact that Wurtzel's book was called Prozac Nation seemed to crystallize the country's mood. It didn't hurt, either, that Wurtzel could be photographed to maximize a certain plaintive, pouty sex appeal.

Nor did it frustrate her publicists that she was a 27-year-old Harvard graduate -- and it is a reality of media coverage that whatever happens at Harvard or to people who went there is deemed newsworthy in a way that the same things, if they happen at Yale or Michigan or Berkeley, or to graduates of those or other universities, are not equally so. Even outside America, Wurtzel received rock-star treatment. I remember being in Stockholm in 1995 and seeing rows of Prozac Nation lined up in the front window of a big downtown bookstore. It has recently been made into a movie starring Christina Ricci, who looks a bit like Wurtzel.

A follow-up book, Bitch -- extolling famously difficult women in history -- stumbled when it developed that the author was strung out on cocaine throughout most of the publicity tour, tottering on the edge of incoherence in national TV appearances.

The new Wurtzel memoir brings us up to date. While she was writing Bitch, in a series of apartments in Ft. Lauderdale, she discovered a new drug: methylphenidate hydrochloride, or Ritalin. Her psychiatrist in New York had prescribed it for her, though Ritalin is thought of as being more suited to elementary-school children suffering from an inability to concentrate on homework. It focuses the mind by speeding it up. As Wurtzel soon found, crushed up and snorted it has an effect quite like cocaine.

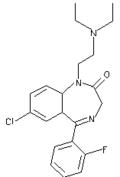

Before long she is recounting the scary math by which an innocuous prescription for four pills daily turns into an addiction to 40 a day, supplemented by whatever other abuse-worthy drugs Wurtzel can lay hands on, having them FedExed from New York or swiping them from friends' medicine cabinets. We learn that plenty of familiar brands, meant to be swallowed, can be ground to powder and sniffed for a greatly enhanced psychotropic effect. Vicodin, Percocet, Tylenol 3, Demerol, Dalmane, Dilaudid, Xanax -- they all work. "Still," she recounts wryly, "I know that Ritalin is not supposed to be addictive, so I don't figure this is really a problem -- I decide it is simply odd behavior. Extremely odd behavior."

Before long she has made the transition to cocaine, which after all isn't merely like cocaine. Returning to New York, still working away obsessively on Bitch, she finally checks herself into a tony, preppy rehab facility in New Haven, Conn., where she falls in love with another brilliant Harvard grad: a drunk named Hank, who will later get her pregnant while he's in a Macallan-induced stupor. After four months in rehab, she relocates again, back to New York, and immediately relapses.

You learn a lot about drugs in this book. For instance, if you want to smuggle cocaine on a flight from Newark to Stockholm, a diaphragm comes in handy: "I take my diaphragm out of my pocketbook -- I've at least had the good sense to make plans for transporting contraband -- I put several little bags of coke into its cup, and then I insert it into myself and make sure it is firmly in place on my cervix. All done."

I didn't know that sniffing cocaine and watching pornography are so inextricably linked. There are also terrifying descriptions of what it's like to come down off a cocaine high that should give pause to the enthusiasts of drug legalization who have never themselves experienced coke or heroin.

The reason to read this book isn't, however, to get an idea of what drugs can do to a typical addict. Yes, Wurtzel gets arrested for shoplifting -- an experience familiar to habitual drug-abusers. But she is no Everywoman. Hardly a chapter goes by without our being reminded, indirectly, of the rich advances and royalties she must have made on Prozac Nation and Bitch. For a freelance writer, she drops serious cash: $60,000 here on rehab, $10,000 there for a contemplated plastic surgery for tummy-maintenance, an undisclosed amount to rent a Tribeca apartment, "this bright new place where the doormen are called concierges." The economics of being Elizabeth Wurtzel are so extravagant that the reader is left puzzled, unable to make it all add up, since she emphasizes that (unlike what seems to be the large majority of artistic types in New York) she doesn't come from family money.

Nor do you get much of a sense of the world around Wurtzel, something that often makes memoirs interesting. Her friends, as they pass in and out of her life, are mainly blanks. There is one named Lily, another named Kathlyn, a Jason, a Betty, a Lydia, but they don't interest Wurtzel very much. One can hardly tell them apart.

But after all, this is a writer who freely admits she's self-absorbed, spoofing her own vanity. Or is it a spoof? A turning point, sort of, occurs when Wurtzel gets coked up and misses a scheduled photo shoot for an ad campaign for Coach, the pricey leather purveyor. Katie Roiphe, another mid-Nineties semi-celebrity girl writer, is hired to replace her. Our heroine seethes: "This Coach bag thing enwreaths me with envy. Now Katie's picture will be in the pages of Vogue, Katie's likeness will be in the window of the Coach flagship store on 57th Street. Katie's -- not mine! . . . For all the dumb things I've done because of drugs, it is this Coach campaign that finally gets to me."

Despite the vanity, her best writing -- and Wurtzel is genuinely talented, fresh and vivid almost as a rule, often very funny -- comes when she's sending herself up. In rehab, she begs an arts-and-crafts instructor to teach her how to weave a basket, "so that I can say that I did the thing that everyone imagines is the craft of choice in mental institutions." There are also some effectively harrowing passages about the sicko things she does to herself when depressed or high, like tweezing hairs out of her legs, plunging in with the "Tweezerman scalpel": "My goal becomes finding a bone, getting far enough into my leg to touch ossified ivory mass, to massage my own skeleton," and -- you get the picture.

Good writing aside, what makes this book significant is almost precisely what made Prozac Nation worth some of the hysteria it generated: Wurtzel is an honest chronicler. There's not much liberal sentimentality here, despite political ravings that crop up -- for example, about the death penalty (which Wurtzel feels that Timothy McVeigh should have been spared). In her first book, the topic -- subterranean, subversive -- was the devastation wrought by divorce. Here the underlying point may be the devastation wrought by the spiritual vacuum of modern life. Wurtzel asserts that what drove her to drugs was an unwillingness to feel any more pain, or even minor annoyance. The drugs numbed all that, at first; but the cure for the addiction, she readily admits, is God.

This is in line with one of the quirkier correspondences in literary history: that between Bill Wilson, founder of Alcoholics Anonymous, and the psychologist Carl Jung. In a 1961 letter, Jung wrote to Wilson of the connection between spirituality and spirits, as in booze. The latter functions as a substitute for the former. When a person is spiritually parched, he may turn to alcohol or narcotics, which give a high, a sense of oneness with the universe, that prayer and religious observance also give (though without the side effects). "You see," wrote Jung, "alcohol in Latin is 'spiritus' and you use the same word for the highest religious experience as well as for the most depraving poison. The helpful formula therefore is: spiritus contra spiritum." That's why the renowned Twelve Step method of AA posits belief in "a Power greater than ourselves" as a precondition to recovery, and is so insistent on this (Steps Two and Three) that competing recovery methods have sprung up for those addicts committed to a faith in secularism. (The competing programs don't seem to work as well as the traditional Twelve Steps.) In the true turning point in Wurtzel's book, after which it appears that the author has given up cocaine for good, she is on her knees in prayer.

It's no coincidence that the book's dramatic climax is a visit to an abortion clinic. There Wurtzel meets a 20-year-old woman, six months pregnant, whose abortion will require two days of surgery. Of her own experience, she says, "I get full anesthesia, which I am told is for my own good, but I later realize it is because that allows the doctor to work quicker, to perform more abortions in less time. . . . As the anesthesiologist fits the suction mask on my face that releases the ether into my system, I am grateful. I don't want to know."

Later she wakes up. "All I see is girls. Two rows of cots, at least twenty along each side of the room, all with girls in blue smocks, curled into fetal position, wrapped in baby blue blankets on white pillowcases and white sheets. In an aerial photograph, we would all look the same. We would look like rows of pastries coming out of the oven on a baker's tray." Fully appreciating the horror of this scene, Wurtzel works herself into a pretzel explaining why this should remain a legal form of medical practice -- because that is what the urbane intended readership of this book will want to hear. But she concludes, "I'm left with a feeling that no one should have an abortion."

Life is sanctified, it would seem, and there is another, transcendent reality -- her readers are left with these two thoughts. It's not what you would expect from a volume with this one's back cover -- a photo of the author, with diamond nose stud, bleached blonde tresses, and a bicep tattoo with a heart and a word written in the middle (it looks like "PURE," possibly "PUKE").

She writes, in the final pages, despite the apparent surrender to Heaven, "I want so badly to believe in God" -- suggesting that she hasn't yet taken Steps Two and Three. Or has she? In the acknowledgements, she thanks a pair of Orthodox Jewish organizations, the Chai Society at Yale University and Chabad House of Ft. Lauderdale, which haven't been mentioned earlier in the book. So who knows what steps she might have taken after the narrative was completed? Whatever the case, Elizabeth Wurtzel is an intriguing girl who has succeeded in sneaking some dangerously good ideas into places, and into the minds of readers, where ideas like that aren't normally encountered. This is a valuable and important service.

COPYRIGHT 2002 National Review, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2002 Gale Group