QUESTION: My medical unit admits many elderly patients with chronic pain. I understand that some analgesics aren't recommended for elderly patients. What's a good source of information for treating pain in the elderly?

ANSWER: The American Geriatrics Society (AGS) revised its guideline, Management of Persistent Pain in Older Persons, in May 2002. The guideline focuses on managing chronic (also called persistent) pain in patients with limited social and financial resources.

Many older patients experience persistent pain, and it's not necessarily associated with a recognizable disease process. Many effective treatments are available for persistent pain, but four drugs generally aren't recommended because they're especially risky for elderly patients:

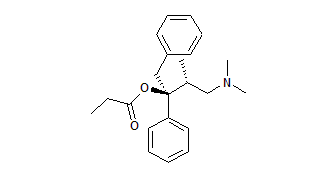

* Propoxyphene (combined with aspirin as Darvon or with acetaminophen as Darvocet) is more toxic than aspirin and acetaminophen and no more effective.

* Tramadol may induce seizures.

* Methadone is risky to use in elderly patients because its long and variable half-life makes the dose difficult to titrate.

* Mependine, which isn't effective as an oral analgesic, can quickly cause toxicity in elderly patients when normeperidine, its active metabolite, accumulates in the body.

Taking the right approach

The AGS guideline discusses four broad pain categories-persistent, severe, moderate, and mild-and offers general approaches to treatment for each.

Patients with persistent pain may respond better to around-the-clock dosing than to intermittent dosing, which may let pain get out of control. Provide short-acting analgesics for breakthrough pain and before painful procedures.

Some types of persistent pain respond to adjuvant drugs such as antiarrhythmic medications, antidepressants, and anticonvulsants. The best drug is one that provides the most pain relief with the lowest risk of adverse reactions.

An opioid such as morphine is the best choice for a patient in severe pain. Monitor him for adverse reactions, such as gait disturbance, pruritus, nausea, sedation, impaired concentration, constipation, and respiratory depression. Mild sedation and impaired cognitive function are common when therapy with an opioid starts, so initiate fall precautions. Adverse reactions tend to resolve as therapy continues and the patient develops physical tolerance to the drug.

Opioids commonly cause constipation, so make sure the patient drinks plenty of fluid, walks and exercises regularly (if his condition permits), uses the toilet regularly, and takes a stimulant, such as senna. Because constipation is an adverse effect that doesn't decrease over time, help him plan an ongoing bowel regimen.

Your patient may worry about the risk of opioid addiction. Explain the difference between tolerance and addiction and reassure him that taking an opioid for pain control rarely leads to addiction.

As your patient develops tolerance to an opioid, he may need a higher dosage to maintain pain relief. Explain that this is a predictable consequence of long-term opioid use and doesn't mean he's addicted. Evaluate him for new or worsening disease whenever he needs a dosage increase.

For patients with mild to moderate pain, acetaminophen is the first choice. But elderly patients, especially those with liver or renal disorders and those who drink alcohol, should take substantially less acetaminophen than the maximum recommended dosage of 4 grams/day. If necessary, the patient can switch to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) unless contraindicated by underlying medical conditions, such as heart failure. For long-term therapy, selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors such as celecoxib or rofecoxib, which are gentler on the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, are preferred to nonselective NSAIDs. Warn the patient about the risk of GI bleeding and tell him to take the drug with food.

Tailoring treatment

Work with the patient and his primary care provider to tailor an analgesic regimen that meets his needs. An elderly patient may be more sensitive to some drugs and especially susceptible to adverse reactions, so monitor him closely.

By becoming familiar with the AGS guideline, you can keep an elderly patient's pain under control and help him remain active.

SELECTED REFERENCE

American Geriatrics Society Panel on Persistent Pain in Older Persons: "The Management of Persistent Pain in Older Persons," Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 50(Suppl., 6):205-224, June 2002.

BY BARBARA ACELLO, RN

Barbara Acello is an independent nurse-consultant specializing in geriatrics and long-term care. She lives in Denton, Tex.

Copyright Springhouse Corporation Oct 2003

Provided by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights Reserved