Clinical Scenario

A 35-year-old man comes to you for follow-up after his third emergency department visit for continued intermittent chest pain. He has no cardiac risk factors and his electrocardiography (ECG) and stress test results were normal in the emergency department. You suspect a noncardiac cause for his chest pain.

Clinical Question

What is the best way to treat noncardiac chest pain?

Evidence-Based Answer

Noncardiac chest pain can be caused by gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), panic disorder, or a number of other psychological conditions. Psychotherapy, particularly cognitive behavior therapy, has been shown to reduce the number of days with chest pain significantly over a three-month period, whatever the cause. (1)

Practice Pointers

The cause of chest pain for patients presenting to emergency departments most commonly is noncardiac. Epidemiologic studies have not been conclusive, but noncardiac chest pain is thought to affect about 25 percent of the U.S. population, with equal distribution among men and women. As such, it also is seen commonly in primary care and pain is not related to cardiac disease does not prevent patients with noncardiac chest pain from experiencing significant functional impairment. This translates into high medical care usage, including hospitalization and inappropriate cardiac medication. The cause of noncardiac chest pain is most commonly GERD or panic disorder, although other gastrointestinal motility diseases and psychiatric diseases also figure prominently. (2,3) Even when the cause is gastrointestinal, there often is significant psychiatric comorbidity, as there is with GERD without noncardiac chest pain. (4) Chest pain in children rarely is related to the heart and is thought to be most commonly musculoskeletal, although children with chest pain can have increased anxiety-related symptoms. (2)

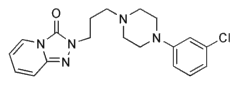

Patients who are evaluated in the emergency department and diagnosed with non-cardiac chest pain often are not treated for their chest pain in that setting. The assumption is that the anxiety evident in the patient will be eased with the reassurance that they do not have heart disease. This does not seem to be true. Patients with noncardiac chest pain show more cardiac awareness and cardioprotective behavior than those with actual cardiac disease, and noncardiac chest pain may persist for years. (5) Noncardiac chest pain can be difficult to treat. Empiric treatment with high-dose omeprazole (Prilosec) can benefit patients in whom GERD is suspected. (6) Trazodone (Desyrel) and imipramine (Tofranil) also have been investigated as possible treatments for non-cardiac chest pain, although the studies were small. (4)

The authors of this Cochrane review (1) analyzed psychotherapy as treatment for noncardiac chest pain and found a modest benefit. Patients received from one to 12 sessions of therapy. Although the interventions varied, almost all included breathing exercises, and most also included cognitive restructuring and relaxation exercises. In some studies, the intervention also included problem solving, physical exercise, and graded exposure. Cognitive behavior therapy can be carried out in individual or group settings and can be administered by a physician, nurse, psychologist, or other trained professional.

The Cochrane Abstract below is a summary of a review from the Cochrane Library. It is accompanied by an interpretation that will help clinicians put evidence into practice. Katherine L. Margo, M.D., presents a clinical scenario and question based on the Cochrane Abstract, followed by an evidence-based answer and a full critique of the review.

This clinical content conforms to AAFP criteria for evidence-based continuing medical education (EB CME). EB CME is clinical content presented with practice recommendations supported by evidence that has been reviewed systematically by an AAFP-approved source. The practice recommendations in this activity are available online at http://www.cochrane. org/cochrane/revabstr/ AB004101.htm.

REFERENCES

(1.) Kisely S, Campbell LA, Skerritt P. Psychological interventions for symptomatic management of non-specific chest pain in patients with normal coronary anatomy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;(1):CD004101.

(2.) Eslick GD. Noncardiac chest pain: epidemiology, natural history, health care seeking, and quality of life. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2004;33:1-23.

(3.) Goodacre S, Mason S, Arnold J, Angelini K. Psychologic morbidity and health-related quality of life of patients assessed in a chest pain observation unit. Ann Emerg Med 2001;38:369-76.

(4.) Olden KW. The psychological aspects of noncardiac chest pain. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2004;33:61-7.

(5.) Esler JL, Bock BC. Psychological treatments for noncardiac chest pain: recommendations for a new approach. J Psychosom Res 2004;56:263-9.

(6.) Wang WH, Huang JQ, Zheng GF, Wong WM, Lam SK, Karlberg J, et al. Is proton pump inhibitor testing an effective approach to diagnose gastroesophageal reflux disease in patients with noncardiac chest pain? A meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med 2005;165:1222-8.

KATHERINE L. MARGO, M.D., is predoctoral director and assistant professor in the Department of Family Practice and Community Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, Philadelphia, where she also is associate residency director. She received her medical degree from the State University of New York Upstate Medical Center, Syracuse, and completed a family medicine residency at St. Joseph's Hospital in Syracuse.

Address correspondence to Katherine Margo, M.D., Department of Family Practice and Community Medicine, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, 2 Gates/3400 Spruce St., Philadelphia, PA 19104 (e-mail: margok@uphs.upenn.edu). Reprints are not available from the author.

COPYRIGHT 2005 American Academy of Family Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2005 Gale Group