INTRODUCTION

Drug abuse, both illicit and licit, is an ongoing serious national problem. To date, neither prevailing social policies, law enforcement apparatus (national and local) nor community efforts have been able to contain the problem and its devastating consequences. Like a multi-headed hydra, it regenerates itself in new forms. The abuse of dextromethorphan-based cough syrup could become a new national problem with profound implications if teenage experimentation with the drug becomes part of the search for substitutes for some better-known substances in order to get "high."

The improper use of drugs for nonmedical purposes not only is damaging to health, but is harmful to society in many profound ways. The drugs in question, as noted, may be classified in two broad categories: (1) licit psychoactive drugs such as caffeine, alcohol, and nicotine, as well as over-the-counter preparations, including pain killers and cold medications; and (2) the illicit psychoactive drugs such as cocaine, heroin, and marijuana. The forms of abuse include experimental use (a short-term trial); social recreational use (occasional indulgence among friends to share an experience); circumstantial (situational use in specific stressful circumstances); intensified use (long-term, regular, and habitual use); and compulsive use (frequent use of the drug to the point where an individual becomes physiologically and/or psychologically dependent) (Jones, Gallagher, & McFalls, 1988). The primary focus of this paper is to construct a theoretical framework with regard to the factors that make dextromethorphan-based cough syrup an attractive choice for experimental abuse or misuse.

Background

A recent study conducted by the University of Michigan's Institute for Social Research reported a significant drop in illegal drug abuse among high school seniors (U.S. Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration, 1991) However, a national poll of U.S. citizens reported ". . . drug abuse in general and teenagers' drug use in particular [as being] this nation's number one problem" (Eggert & Herting, 1991, p. 482). The National Institute on Drug Abuse also has reported only a modest decline in drug usage. Further, ". . . health officials see a new and terrifying danger--teenagers who regularly abuse and combine many different drugs end up with shattered and impotent lives" (Downey, 1991/1992, p. 264).

A wide range of drugs are being used by teenagers. Among students studied by Miller and Gold (1991), 10 to 13% reported use of inhalants. According to Eggert and Herting (1991), over 55% of high school students used illicit drugs, mostly those that are easily obtained, typically from their own homes. They may include alcohol, codeine, marijuana, or paint. "Hard" drugs, such as heroin, crack, and PCP were rarely used by teenagers according to Lewandowski and Westman (1991).

Drugs are used (experimentally or habitually) for many reasons, the most common of which is to produce an immediate euphoric effect. Other reasons frequently reported by students include ". . . to make me more popular with my friends; so people would like me; because my parents used them; because someone else wanted me to; to make me feel more like an adult; because my friends use drugs; because it was a habit, and because I could make extra money selling them" (Novacek, Raskin, & Hogan, 1991, p. 483). Novacek also discovered that ". . . the more reasons people have for using drugs and alcohol, the more frequently they use them." p. 476).

Other studies show abuse of licit drugs to be a precursor of illicit drug use. "History of solvent use may indicate individuals at high risk for intravenous drug abuse and youths who have used solvents should be considered at high risk for severe drug abuse, including IVDA [intravenous drug abusers]" (Dinwiddie, Ruch, & Cloninger, 1991.)

An important consequence of teenage drug abuse appears to be the increase in suicide rates: 28,100 suicides are reported per year among 15- to 24-year-olds (Downey, 1990/91). "All available evidence suggests substance abusers are at increased risk for suicide" (Downey, 1990/91, p. 266). Drugs have been reported as the primary method used in adolescent suicide attempts. In addition, ". . . the suicide rate among alcoholics is an astonishing 58 times higher than that of the general population, with approximately one out of every three suicides in the population alcohol-related" (Downey, 1990/91, p. 267).

Theoretical Framework

Experimentation of any kind, whether motivated by external factors, curiosity, or necessity, always has an underlying objective. When teenagers engage in the misuse or abuse of drugs or other substances for experimentation, invariably, the objective except for the commission of suicide, is to get "high." The intent is to discover a substitute for drugs or substances currently used.

Most often the abuse or misuse of drugs or substances by teenagers begins with experimentation. According to Novacek et al. (1991) 46% and 58% of middle and high school students, respectively have tried cigarettes and alcohol at least once. The experimentation also includes other licit substances such as inhalants. For example, a national survey conducted from 1975 through 1982 indicated that up to 11% of high school seniors admitted misusing amyl and butyl nitrates (Miller & Gold, 1991).

Young persons are seeking euphoria, excitement, sedation, light-headedness, delusions, and visual and auditory hallucinations (Miller & Gold, 1991). The motivation to experiment may come from peer pressure, curiosity, or the unavailability of the desired drugs.

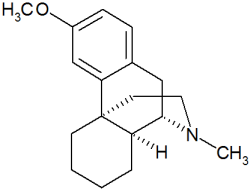

Much experimentation may be temporal, but in many instances, for example, smoking cigarettes or drinking alcohol, can become long-term addictive behavior. Experimentation may also lead to the habitual use of harder, illicit, and more addictive drugs (Novacek et al., 1991; Dinwiddie et al., 1991). When it becomes habitual, it ceases to be an experiment and there is often a tendency to seek a drug with a longer lasting high (Trebilcock, 1993). For example, "huffing" glue or gasoline may eventually lead to the abuse of cocaine. A study done by Dinwiddle et al. (1991) showed that 33% of IVDAs studied reported a prior history of solvent abuse. Thus, the widespread and frequent misuse or abuse of any drug for experimentation by teenagers is a potential social problem. It is still unclear, however, what factors determine the choice of drug or substance for experimentation considering the wide range of choices. Recently, Dextromethorphan-based cough syrups have been reported to be among the choices. Dextromethorphan (DM), the dextro insomer of the codeine analog of leborphanol, is a cough suppressant ingredient in more than 75 preparations sold over the counter (OTC) without prescription. The drug was first marketed as a prescription antitussive in the early 1950s and became OTC in 1956 (Fisher, 1991; Andel, Myers, Szucs, & Rosenburg, 1991). Reports of abuse of cough syrups containing DM date to the early 1960s, but the evidence is primarily anecdotal (Andel et al., 1991).

Dextromethorphan is commercially available in cough syrup in concentrations of 5 to 15 mg/5 ml and in a variety of sizes. Recent medical literature suggests that use in large quantities may produce phencyclidine (PCP) - like effects by the metabolic conversion of DM to its immediate metabolite Dextrorthan (DO) (Fisher, 1991). In order to achieve the desired state of inebriation, large quantities of cough syrup are ingested: 4 to 20 ounces daily. The PCP-like effects include bizarre and hyperactive behavior as well as hallucinations (Krenzelok, 1990). A number of factors may explain the appeal of cough syrup as a substitute for other drugs or substances.

Availability factor. It is frequently argued that if the use of drugs or similar substances is legally restricted, thereby making availability and accessibility difficult, people will search for nonrestricted substitutes. For similar reasons, in terms of accessibility and cost, both inhalants and cough medication are more attractive as substitutes than are legally restricted drugs such as marijuana or cocaine. "A kid can get high on and off all day for under a dollar on a can of butane . . . [It's] cheap, legal, and convenient" (Trebilcock, 1993, p. 78). Drugs such as cough syrup are not legally restricted to teenagers and do not require a prescription. Cough syrups are available over the counter in almost all drug stores, most food markets, and in the medicine cabinet of the average American household.

Approval factor. Similarly, there is an assumed correlation between the choice of a substitute and its social approval. For example, cough syrup would be a better choice for experimentation or substitution than glue or butane because the use of the former does not bear the same socially negative connotations as the latter.

Ignorance factor. The less that is known about the negative physiological and psychological effects of a substance, the greater its appeal. With both inhalants and cough medication, little is known about the negative effects of their abuse. Sniffers of butane and gasoline do not consider (or are not aware of) its potentially fatal effects. They are focused on the prospects of immediate "thrills." Again, the social connotations have a reinforcing effect. As noted by Trebilcock (1993), the attitudes of friends and family members of a teenage boy who died of inhalant abuse were ". . . at least he's not doing drugs," and ". . . she [his mother] didn't realize inhalants were deadly." Even though psychological effects such as confusion, depression, and neurosis are often associated with inhalation of various chemicals (Miller & Gold, 1991), and alcohol ". . . is one of the most destructive [drugs] from both a physiological and psychological standpoint . . . playing a role in 70% of students studied who committed suicide (Downey, 1990/91, pp. 267-268), these negative effects may not be commonly known among the users.

One may argue that children know very little about the negative psychological and physiological effects of such socially approved substances as the caffeine in coffee, tea, and sodas and yet those are not common choices for experimentation or abuse. The response is that these do not have the intoxicating effects that often form the basis of experimentation.

Fear factor. Although consuming the necessary amount of cough syrup to get high may be difficult, it does not have the intimidating qualities to the abuser of a pill such as aspirin, powders, or needles (Trebilcock, 1993). Taking three or more pills of anything bears the threat or connotation of suicide. Powders or needles, if not prescribed, are often associated with harder, more addictive, illicit, and dangerous drugs or substances. Since cough syrup, on the other hand, is devoid of these qualities or connotations, it is relatively easier for a curious teenager to be induced to experiment with it.

These four factors--availability, approval, ignorance, and fear --provide the framework for a theory of substitution grounded in the following hypotheses: (1) There is a positive relationship between the potential or actual abuse of a drug and its legality or ease of availability; (2) there is a positive relationship between social acceptability and potential for abuse; (3) there is a negative relationship between the abuse and knowledge of the negative physiological and psychological effects; and (3) there is a negative relationship between the intimidating qualifies and experimental misuse or abuse.

From these hypotheses one may logically deduce that: (1) Licit, over-the-counter drugs are more likely to be abused than illicit or prescription drugs. For example, cough syrup, aspirin, Tylenol, or inhalants have greater potential for abuse than marijuana, LSD, or cocaine; (2) Comparing licit and equally available drugs, cough syrup and Tylenol are more likely to be abused than airplane glue. The former are not only more socially acceptable, but less is known about their negative effects, and their medicinal function serves as an excellent disguise for abuse; (3) Comparing cough syrup with Tylenol, because of its relatively more intimidating qualities, the latter is less appealing as a choice for experimentation.

As indicated, DM-based cough syrup is more readily available and more socially acceptable than licit substances such as inhalants. Compared to other drugs of equal social acceptability, for example, Tylenol, less is known about the negative psychological and physiological effects of cough syrup. Many people may be aware of the potential for abuse of Tylenol; for example, an overdose on "pills" is a common method of attempted suicide. "Drug ingestion has been reported by numerous researchers to be the primary method used among adolescent suicide attempters" (Downey, 1990/91, p. 266). However, cough medication is not viewed as a means of committing suicide.

Also, unlike other licit drugs such as nicotine and alcohol, DM is available over the counter to all age groups, and it is not associated with any widely known effects as nicotine is for lung cancer and alcohol for cirrhosis of the liver and a cause of auto accidents. As a consequence of the fact that it is relatively cheap, legal, easily available, and that its physiopsychological implications are not fully established or known to the potential abuser population, the abuse of DM-based cough syrup as a potential social problem is great.

In order to explore this theory concerning the substitution of DM-based cough syrup for other drugs, a comprehensive study that will generate information on all aspects of the phenomenon is imperative. Such a study should be designed to identify effective methods of intervention.

REFERENCES

Andel, M., Myers, V.A.S., & Rosenburg, J.M. (1991). What is the abuse potential of dextromethorphan? Hospital Pharmacist Report, July, 18.

Dinwiddie, S., Reich, T., & Cloninger, C. (1991). Solvent use as a precursor to intravenous drug abuse. Comparative Psychiatry, 32(2), 133-140.

Downey, A.M. (1990/1991). The impact of drug abuse upon adolescent suicide. Omega, 22(4), 261-275.

Eggert, L.L., & Herting, J. R. (1991). Preventing teenage drug abuse: Exploratory effects of network social support. Youth & Society, 22, 482-524.

Fisher, J.D. (1991). Dextromethorphan. Clinical Toxicology Review, 13, 1-2.

Jones, B.J., Gallagher, B.J. III, & McFalls, J.A. Jr. (1988). Social Problems: Issues, opinions, and solutions. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Krenzelok, E.P. (1990). Non-prescription cough medicine abuse. Clinical Toxicology Forum, 2, 5.

Lewandowski, L., & Westman, A. (1991). Drug use and its relation to high school students' activities. Psychological Reports, 68, 363-367.

Miller, N.S., & Gold, M.S. (1991). Organic solvent and aerosol abuse. American Family Physician, 44(1), 183-189.

Novacek, J., Raskin, R., & Hogan, R. (1991). Why do adolescents use drugs? Age, sex, and user differences. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 20, 475-492.

Trebilcock, B. (1993, March). The new high kids crave. Redbook, 180(5), 76-78, 118-120.

United States Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration. (1991). Drug use among American high school seniors, college students and young adults. 197-1990. (Report No. 91-1813.) Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Tamara K. Richards, Graduate Department of Criminal Justice, Shippensburg University, Shippensburg, Pennsylvania.

Reprint requests to Momodou N. Darboe, Ph.D., School of Natural and Social Sciences, Shepherd College, Shepherdstown, West Virginia 25443.

COPYRIGHT 1996 Libra Publishers, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group