**********

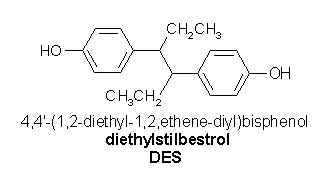

Between 1938 and 1971, as many as 4 million women in the United States took diethylstilbestrol (DES), an oral synthetic nonsteroidal estrogen, for the purpose of improving pregnancy outcomes. (1,2) In 1953, it was demonstrated that DES did not prevent miscarriage and other pregnancy complications. However, physicians continued to prescribe DES to pregnant women until at least 1971, when a connection was established between in utero DES exposure and the development of clear cell adenocarcinoma of the vagina and cervix in the daughters of women who had taken DES during pregnancy. (3) In 1971, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration issued a warning against the use of DES in pregnant women. (4) DES continued to be used in various European countries until the early 1980s.

The association between in utero DES exposure and vaginal clear cell adenocarcinoma has been well documented. Other adverse associations have been identified in DES-exposed women and their offspring, and animal studies have shown effects in the next generation (grandchildren). (5,6) The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has instituted a campaign to educate health care professionals and patients about the risks associated with exposure to this synthetic estrogen.

It is difficult to determine the number of persons with DES exposure. However, physicians should be alert for patients who may have been exposed to this agent and should be aware of the possible consequences of such exposure. Dosages of DES varied greatly, as did the time during pregnancy that DES was taken. These factors may contribute to the wide range of adverse effects in the offspring of women who took DES while they were pregnant.

Illustrative Case

A 37-year-old woman who had been trying to conceive for two years came to her physician's office to discuss fertility issues. Her basal body temperature charts illustrated presumed ovulatory cycles, and her husband had a normal semen analysis. She had an abnormal Papanicolaou (Pap) smear 15 years previously, but all subsequent Pap smears had been normal. However, her previous physician had noted that her cervix "looked funny." The patient was the oldest of four siblings; her mother had two miscarriages before the patient was born.

The patient's general physical examination was normal. On pelvic examination, her vagina was normal, but her cervix had a pseudopolyp. Because of the patient's history of infertility and the consideration that she might have been exposed to DES in utero, hysterosalpingography was ordered, and the patient was asked to discuss the possibility of DES exposure with her mother.

The patient's mother accompanied her to the follow-up visit. The hysterosalpingogram showed that the patient had a T-shaped uterus. Her mother vaguely remembered taking medication to prevent another miscarriage when she was pregnant with her daughter.

Subsequent to a follow-up visit, the patient's mother contacted her physician for a copy of her obstetric records. The patient was referred to a reproductive endocrinologist for evaluation of infertility.

Identifying DES Exposure

It is important to include questions about DES in the routine medical history of women who gave birth between 1938 and 1971, and of patients who were born during those years (3,7) (Table 1). (2) In persons born outside the United States, there is a chance of DES exposure if they gave birth or were born as late as the 1980s. Many women may not be aware that they received DES during pregnancy, in part because the synthetic estrogen was marketed under many different names. (2,8)

One recent study (9) found that an office system intervention was successful in increasing awareness of DES exposure among clinical staff. The intervention entailed the addition of questions about DES exposure to the routine health history form.

Women Who Took DES During Pregnancy

Women who took DES while they were pregnant have a slightly higher incidence of breast cancer compared with the general population. The relative risk ranges from 1.27 to 1.35 in several studies. (10) In comparison, the relative risk of breast cancer is 1.3 in women who have taken hormone therapy for more than five years,11 and 2.1 in women with a family history of breast cancer. (12) Women who were prescribed DES during pregnancy should have annual mammography and clinical breast examinations after the age of 50. (12) [Strength of recommendation (SOR) A, evidence-based guideline]

No increased risk of other hormone-dependent cancers has been found in women with DES exposure during pregnancy. Therefore, other preventive and screening measures should be based on standard guidelines.

Daughters with in Utero DES Exposure

In the daughters of women who took DES during pregnancy, the incidence of clear cell adenocarcinoma of the vagina and cervix ranges from 1.4 cases per 1,000 exposed persons to one case per 10,000 exposed persons. (13) Clear cell adenocarcinoma is most likely to develop when women with in utero DES exposure are between 17 and 22 years of age. However, cases have been diagnosed in women in their 30s and 40s, and there is concern about a possible second age-incidence peak of clear cell adenocarcinoma as women with in utero DES exposure grow older. (14) Clear cell adenocarcinoma of the vagina and cervix is rare in women without in utero DES exposure; in such cases, the cancer usually develops in the postmenopausal period. (15)

Many women who were exposed to DES in utero are just beginning to reach menopause. Because of the concern about a second peak in the incidence of clear cell adenocarcinoma, continued surveillance for this cancer is warranted in these women. (16)

Women with in utero DES exposure do not have a higher documented incidence of any other cancer. Data from several studies (17,18) suggest that these women may have a higher incidence of high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, but not invasive cervical carcinoma. However, the findings of these studies have been questioned, in that women with in utero DES exposure may receive increased cytologic screening. A link with breast cancer is under investigation. (2)

Many women who were exposed to DES in utero have a range of structural reproductive tract abnormalities (19,20) (Table 2). The National Collaborative Diethylstilbestrol Adenosis project (19) followed approximately 4,500 DES-exposed women for almost 20 years and found an 18 percent incidence of structural uterine, cervical, or vaginal abnormalities. The incidence of these abnormalities may be as high as 33 percent in women with in utero DES exposure. (2)

DES can cause changes in the vaginal epithelium, including adenosis (columnar epithelium located in the upper one third of the vagina). Although vaginal adenosis is benign, it sometimes causes abnormal bleeding. The degree of adenosis depends on the DES dosage and the stage during the pregnancy that the agent was taken. The most severe changes occur in the daughters of women who took DES during the first trimester. (20) Although vaginal clear cell adenocarcinoma generally develops in areas of adenosis, whether individual areas of adenosis progress to this cancer remains unknown.

Performance of colposcopy (to assess for abnormal epithelium) frequently is recommended during the first pelvic examination in all women with in utero DES exposure (Table 3). (21) If the initial colposcopic examination is normal, annual pelvic examinations and annual cervical Pap smears and fourquadrant vaginal Pap smears are adequate, and colposcopy does not need to be repeated. (21,22) [Reference 22: SOR C, consensus practice guideline based on expert opinion] If the initial colposcopic examination demonstrates any abnormalities, annual colposcopy with cytology is indicated.

For the four-quadrant Pap smear, cells are obtained from all four walls of the upper vagina. Cells first are obtained from the two lateral walls; then the speculum is rotated 90 degrees, and specimens are obtained from the anterior and posterior walls. The fourquadrant Pap smear should be performed annually to screen for adenosis and clear cell adenocarcinoma in women with in utero DES exposure.

Routine cervical cytology also should be performed annually in women who were exposed to DES in utero. In addition, the cervix and upper vaginal walls should be palpated carefully during the bimanual examination to feel for thickening that might indicate adenosis or clear cell adenocarcinoma. (22)

Women with in utero DES exposure should be counseled about their slightly increased risk of infertility and a possibly increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcome. Infertility is most common in women with underlying structural abnormalities and usually is caused by uterine or tubal factors. (23) Women who were exposed to DES in utero should be monitored closely during pregnancy. (24-26)

Although most women with in utero DES exposure have normal pregnancies, there is evidence for an increased risk of first- and second-trimester spontaneous abortion, ectopic pregnancy, and preterm delivery. (26) The most comprehensive study (26) to date found that 64.5 percent of women with in utero DES exposure had full-term infants, compared with 84.5 percent of matched women who had not been exposed to DES. In addition, the DES-exposed women had higher rates of preterm delivery (19.4 percent versus 7.5 percent), ectopic pregnancy (4.2 percent versus 0.77 percent), and second-trimester spontaneous abortion (6.3 percent versus 1.6 percent). Consequently, high-risk obstetric care may be indicated for pregnant women who were exposed to DES in utero.

Contraceptive management may be complicated in women with in utero DES exposure. Use of intrauterine devices is controversial because of the high incidence of structural uterine abnormalities, as well as possible changes in the elasticity of endometrial tissue. Because of cervical abnormalities, diaphragms and cervical caps may be difficult to fit. (27) No evidence indicates that oral contraceptive pills are not safe for use in women with in utero DES exposure, although some experts are reluctant to prescribe hormonal contraception of any type to these women. (3)

Sons with in Utero DES Exposure

The sons of women who took DES during pregnancy are three times more likely to have genital structural abnormalities than men without such exposure. (28) The most common abnormalities are epididymal cysts, undescended testes, and small testes. Epididymal cysts have no clinical implications, but undescended testes and small testes are associated with an increased risk of testicular cancer. (29) Men with in utero DES exposure also have sperm and semen abnormalities but do not have an increased risk of infertility or sexual dysfunction. (30)

There is some concern about the effects of DES on the prostate. (31) One study (32) that examined the prostatic utricle of male stillborns who were exposed to DES in utero showed a significantly higher incidence of squamous metaplasia in this mullerian-derived tissue.

A recent study (33) showed a possibly increased incidence of testicular cancer in men with in utero DES exposure. Although this finding was not statistically significant, the investigators concluded that the connection between DES and testicular cancer "remains uncertain," and suggested that ongoing clinical surveillance would be prudent. Therefore, the sons of women who took DES during pregnancy should be encouraged to practice routine testicular self-examination.

Future Considerations

An increased susceptibility to reproductive tract tumors has been demonstrated in mice that are descended from parents with prenatal DES exposure (i.e., multigenerational effect), (6) but this relationship has yet to be observed in humans. To date, no studies have shown an increased risk of cancer in the offspring of men and women who were exposed to DES in utero. Two studies (34,35) of "DES granddaughters" (third-generation females) have found no health effects related to DES exposure. However, one small study (36) of "DES grandsons" showed an increased risk of hypospadias.

DES currently is being studied as an experimental hormonal treatment (i.e., a type of estrogen therapy) in men with refractory prostate cancer. (37)

REFERENCES

(1.) Stillman RJ. In utero exposure to diethylstilbestrol: adverse effects on the reproductive tract and reproductive performance of male and female offspring. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1982;142:905-21.

(2.) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. DES update. Accessed online February 19, 2004, at: http:// www.cdc.gov/DES.

(3.) Giusti RM, Iwamoto K, Hatch EE. Diethylstilbestrol revisited: a review of the long-term health effects. Ann Intern Med 1995;122:778-88.

(4.) Exposure in utero to diethylstilbestrol and related synthetic hormones. Association with vaginal and cervical cancers and other abnormalities. JAMA 1976;236:1107-9.

(5.) Herbst AL, Ulfelder H, Poskanzer DC. Adenocarcinoma of the vagina. Association of maternal stilbestrol therapy with tumor appearance in young women. N Engl J Med 1971;284:878-81.

(6.) Walker BE, Haven MI. Intensity of multigenerational carcinogenesis from diethylstilbestrol in mice. Carcinogenesis 1997;18:791-3.

(7.) Kaufman RH, ed. Physician information. How to identify and manage DES exposed individuals. Bethesda, Md.: National Cancer Institute, 1995; NIH publication no. 81-2049.

(8.) Kruse K, Lauver D, Hanson K. Clinical implications of DES. Nurse Pract 2003;28(7 pt 1):26-32,35.

(9.) Jackson R, O'Donnell L, Johnson C, Dietrich AJ, Lauridsen J, O'Donnell C. Office systems intervention to improve diethylstilbestrol screening in managed care. Obstet Gynecol 2000;96:380-4.

(10.) Colton T, Greenberg ER, Noller K, Resseguie L, Van Bennekom C, Heeren T, et al. Breast cancer in mothers prescribed diethylstilbestrol in pregnancy. Further follow-up. JAMA 1993;269:2096-100.

(11.) Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, LaCroix AZ, Kooperberg C, Stefanick ML, et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the Women's Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2002;288:321-33.

(12.) Pharoah PD, Day NE, Duffy S, Easton DF, Ponder BA. Family history and risk of breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cancer 1997;71:900-9.

(13.) Melnick S, Cole P, Anderson D, Herbst A. Rates and risks of diethylstilbestrol-related clear-cell adenocarcinoma of the vagina and cervix. An update. N Engl J Med 1987;316:514-6.

(14.) Hanselaar A, van Loosbroek M, Schuurbiers O, Helmerhorst T, Bulten J, Bernheim J. Clear cell adenocarcinoma of the vagina and cervix. An update of the central Netherlands registry showing twin age incidence peaks. Cancer 1997;79:2229-36.

(15.) Kaminski PF, Maier RC. Clear cell adenocarcinoma of the cervix unrelated to diethylstilbestrol exposure. Obstet Gynecol 1983;62:720-7.

(16.) Hatch EE, Palmer JR, Titus-Ernstoff L, Noller KL, Kaufman RH, Mittendorf R, et al. Cancer risk in women exposed to diethylstilbestrol in utero. JAMA 1998;280:630-4.

(17.) Robboy SJ, Szyfelbein WM, Goellner JR, Kaufman RH, Taft PD, Richard RM, et al. Dysplasia and cytologic findings in 4,589 young women enrolled in Diethylstilbestrol-Adenosis (DESAD) Project. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1981;140:579-86.

(18.) Robboy SJ, Noller KL, O'Brien P, Kaufman RH, Townsend D, Barnes AB, et al. Increased incidence of cervical and vaginal dysplasia in 3,980 diethylstilbestrolexposed young women. Experience of the National Collaborative Diethylstilbestrol Adenosis Project. JAMA 1984;252:2979-83.

(19.) Jefferies JA, Robboy S J, O'Brien PC, Bergstralh E J, Labarthe DR, Barnes AB, et al. Structural anomalies of the cervix and vagina in women enrolled in the Diethylstilbestrol Adenosis (DESAD) Project. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1984;148:59-66.

(20.) Kaufman RH. Lower genital tract changes associated with in utero exposure to diethylstilbestrol. In: Apgar BS, Brotzman GL, Spitzer M, eds. Colposcopy, principles and practice: an integrated text and atlas. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2002:383-90.

(21.) Noller K L. Role of colposcopy in the examination of diethylstilbestrol-exposed women. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 1993;20:165-76.

(22.) Diethylstilbestrol. ACOG committee opinion: Committee on Gynecologic Practice. Number 131--December 1993. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 1994;44: 184.

(23.) Palmer JR, Hatch EE, Rao RS, Kaufman RH, Herbst AL, Noller KL, et al. Infertility among women exposed prenatally to diethylstilbestrol. Am J Epidemiol 2001;154:316-21.

(24.) Goldberg JM, Falcone T. Effect of diethylstilbestrol on reproductive function. Fertil Steril 1999;72:1-7.

(25.) Swan SH. Pregnancy outcome in DES daughters. In: Giusti RM, ed. Report of the NIH workshop on long-term effects of exposure to diethylstilbestrol (DES). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, 1992:42-9.

(26.) Kaufman RH, Adam E, Hatch EE, Noller K, Herbst AL, Palmer JR, et al. Continued follow-up of pregnancy outcomes in diethylstilbestrol-exposed offspring. Obstet Gynecol 2000;96:483-9.

(27.) Edelman DA, Badrawi HH. Contraception for women exposed in utero to diethylstilbestrol. Adv Contracept 1988;4:241-6.

(28.) Cosgrove MD, Benton B, Henderson BE. Male genitourinary abnormalities and maternal diethylstilbestrol. J Urol 1977;177:220-2.

(29.) Docimo SG, Silver RI, Cromie W. The undescended testicle: diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician 2000;62:2037-44,2047-8.

(30.) Wilcox A J, Baird DD, Weinberg CR, Hornsby PP, Herbst AL. Fertility in men exposed prenatally to diethylstilbestrol. N Engl J Med 1995;332:1411-6.

(31.) Laitman CJ, Jonler M, Messing EM. The effects on men of prenatal exposure to diethylstilbestrol. In: Lipshultz LI, Howards SS, eds. Infertility in the male. 3d ed. St. Louis: Mosby, 1997:268-79.

(32.) Driscoll SG, Taylor SH. Effects of prenatal maternal estrogen on the male urogenital system. Obstet Gynecol 1980;56:537-42.

(33.) Strohsnitter WC, Noller KL, Hoover RN, Robboy SJ, Palmer JR, Titus-Ernstoff L, et al. Cancer risk in men exposed in utero to diethylstilbestrol. J Natl Cancer Inst 2001;93:545-51.

(34.) Kaufman RH, Adam E. Findings in female offspring of women exposed in utero to diethylstilbestrol. Obstet Gynecol 2002;99:197-200.

(35.) Wilcox AJ, Umbach DM, Hornsby PP, Herbst AL. Age at menarche among diethylstilbestrol granddaughters. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1995;173(3 pt 1): 835-6.

(36.) Klip H, Verloop J, van Gool JD, Koster ME, Burger CW, van Leeuwen FE, et al. Hypospadias in sons of women exposed to diethylstilbestrol in utero: a cohort study. Lancet 2002;359:1102-7.

(37.) Whitesel JA. The case for diethylstilbestrol. J Urol 2003;169:290-1.

SARINA SCHRAGER, M.D., is assistant professor in the Department of Family Medicine at the University of Wisconsin Medical School, Madison. Dr. Schrager received her medical degree from the University of Illinois at Chicago College of Medicine. She completed a family practice residency and a primary care women's health fellowship at MacNeal Hospital, Berwyn, Ill.

BETH E. POTTER, M.D., is a faculty member in the family practice residency program at the University of Wisconsin Medical School, Madison. Dr. Potter received her medical degree from Rush Medical College of Rush University, Chicago, and completed a family practice residency at the University of Wisconsin.

Address correspondence to Sarina Schrager, M.D., University of Wisconsin Medical School, Department of Family Medicine, 777 S. Mills St., Madison, WI 53715 (e-mail: sbschrag@wisc.edu). Reprints are not available from the authors.

The authors indicate that they do not have any conflicts of interest. Sources of funding: work on this article was supported by grants from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Educational Campaign on DES and the University of Wisconsin National Center of Excellence in Women's Health.

COPYRIGHT 2004 American Academy of Family Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group