Osteoarthritis is the leading medical condition for which persons use alternative therapies. (1) Patients often seek alternative therapies after having side effects or gaining incomplete relief of symptoms with conventional medications. Alternative therapies used for the treatment of osteoarthritis include herbs, supplements, and nondrug modalities such as exercise, physical therapy, acupuncture, and electromagnets. Unlike manufacturers of conventional medications, the herbal and supplement industry is not regulated by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA); therefore, supplement composition (i.e., proportion of active ingredient in a preparation) usually varies. Physicians should be familiar with evidence regarding the safety and efficacy of alternative modalities used to treat osteoarthritis, so they can provide their patients with accurate and up-to-date information.

Glucosamine

Glucosamine sulfate, which is derived from oyster and crab shells, is a popular treatment for osteoarthritis symptoms. In vitro studies (2) have shown that glucosamine stimulates cartilage cells to synthesize increased amounts of glycosaminoglycans and proteoglycan ground substance. High dosages of glucosamine have been shown to have mild anti-inflammatory effects in animal models. (3) No published studies document arthroscopic improvement in arthritic cartilage with glucosamine use in humans.

Most human clinical trials (4-7) have been relatively short term and have had varied results. A recent meta-analysis, funded by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), concluded that glucosamine may show some efficacy over placebo in relieving painful symptoms. (8) [Evidence level A, meta-analysis]

A recent Cochrane Review concluded that current evidence from clinical trials (1) does not analyze the long-term effectiveness and toxicity of glucosamine; (2) does not differentiate which joints and which levels of severity of osteoarthritis warrant this therapy; (3) does not differentiate which dosage and route of administration are best; and (4) does not demonstrate whether glucosamine modifies the long-term progression of osteoarthritis. (9) [Evidence level B, systematic review of lower-quality randomized controlled trials (RCTs)] In addition, 75 percent of the trials analyzed in the Cochrane Review (9) used one brand exclusively, thus failing to shed light on the numerous other preparations available.

There have been no published studies documenting arthroscopic regeneration of articular cartilage following glucosamine administration. Glucosamine is supplied in tablets and capsules. The usual dosing schedule for glucosamine is 1,500 mg per day in three divided doses (9) (Table 1). Research suggests that the supplement must be taken for at least one month before improvement in symptoms can be expected to occur. (8) Glucosamine has been shown to be well tolerated, with few significant side effects (mainly gastrointestinal discomfort) compared with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS).

Chondroitin

Chondroitin sulfate also has demonstrated efficacy in improving the symptoms of osteoarthritis by acting as a building block of proteoglycan molecules. (8,10,11) Commercially available chondroitin is derived mostly from shark and cow cartilage and is supplied in tablet and capsule form.

Like glucosamine, chondroitin's mechanism of action in osteoarthritis may involve both anti-inflammatory properties and substrate provision for proteoglycan synthesis. However, as with glucosamine, the role of substrate provision is theoretic and has not been proved to affect cartilage regeneration or repair.

Two recently published meta-analyses indicated that chondroitin may be superior to placebo in reducing the pain of osteoarthritis. (8,12) [Reference 12--Evidence level A, meta-analysis] One of these analyses (8) cautioned that study results may have been exaggerated by publication bias related to the manufacturer's sponsorship. The second meta-analysis (12) found chondroitin to be superior to placebo in reducing the painful symptoms of osteoarthritis, but researchers cautioned that trials with larger cohorts of patients and over longer periods must be conducted to substantiate these claims. However, these studies suggest that chondroitin improves the symptoms of osteoarthritis.

Comparison of chondroitin with NSAIDs has shown that patients with osteoarthritis have fewer gastrointestinal side effects with chondroitin. Chondroitin is well tolerated; it appears to have a slower onset of action but to work longer than NSAIDS. (13) Overall, chondroitin may offer a safe alternative in the treatment of the symptoms of osteoarthritis. The usual dosing schedule for chondroitin is 1,200 mg per day in three divided doses (Table 1). As with glucosamine, research indicates that the supplement must be taken for at least one month before any symptom relief occurs. (8)

Glucosamine/Chondroitin Combinations

The use of glucosamine and chondroitin together for the treatment of osteoarthritis has become extremely popular; however, there is little evidence that this combination is any more effective than either supplement alone. (14) A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (15) studied the effect of a combination of glucosamine, chondroitin, and manganese ascorbate on osteoarthritis of the knee and lower back. The combination was given for 16 weeks to 34 men in the United States Navy. A significant improvement was found in subjects who had knee symptoms but not in those with low back symptoms. No significant side effects were reported.

Currently, the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM), which is part of the NIH, is conducting the Glucosamine/Chondroitin Arthritis Intervention Trial (GAIT), which will compare the efficacy of glucosamine, chondroitin, a glucosamine/chondroitin combination, a cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitor (celecoxib), and placebo in the treatment of knee pain associated with osteoarthritis.

S-Adenosylmethionine

S-adenosylmethionine (SAMe) is a naturally occurring compound found in all living cells that is commercially produced in yeast-cell cultures. A methyl donor, it is important in methylation reactions that aid in the production of cartilage proteoglycans. (16) SAMe has been available by prescription in Europe since 1975, where it is used to treat arthritis and depression. (17) A number of studies have found SAMe to be more effective than placebo in improving pain and stiffness related to osteoarthritis. (18-22) However, many of these studies were nonrandomized, uncontrolled, and unblinded, and some were flawed statistically. No studies documenting disease arrest or reversal are found in the literature. (17) There is, however, some evidence that SAMe is often as effective as NSAIDs, with a lower incidence of side effects. (18,21-27)

Persons interested in using this agent may find SAMe to have a prohibitively high cost. Reported dosage ranges vary from 400 to 1,200 mg per day. (18,21-27) Side effects include occasional gastrointestinal disturbances, mainly diarrhea. (17)

Cetyl Myristoleate

A new agent promoted for osteoarthritis treatment is cetyl myristoleate, a material synthesized from cetyl alcohol and myristoleic acid. The rationale for its use in osteoarthritis stems from the hypothesis that cetyl myristoleate may inhibit the cyclooxygenase and lipoxygenase pathways of arachidonic acid metabolism and, therefore, decrease production of pro-inflammatory prostaglandins and leukotrienes. Physicians should hesitate to advocate the use of this product until higher-quality clinical evidence has been published.

Ginger

Ginger (Zingiber officinale), obtained from the root of the ginger flower, has been used in Ayurvedic medicine (a traditional Hindu system of medicinal practices using combinations of herbs, purgatives, rubbing oils, etc.) for the treatment of inflammation and rheumatism. It is believed that ginger inhibits prostaglandin and leukotriene synthesis. (22) A recent randomized trial (28) comparing ginger and ibuprofen showed greater efficacy of ibuprofen and no significant difference between ginger and placebo. No side effects or drug interactions have been reported.

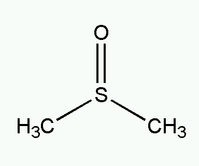

Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO)

Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), a sulfur-containing substance produced from wood pulp, (29) has been used topically for relief of osteoarthritis symptoms. It is a scavenger of reactive oxygen species, and it functions as an anti-inflammatory agent. (30)

One study (31) conducted in Germany examined the effect of percutaneous treatment with DMSO in patients with osteoarthritis. In this double-blind, placebo-controlled study, daily use of a 25-percent gel preparation of DMSO for three weeks resulted in improvement in pain symptoms during activity and at rest. These results have not been replicated in any trials in the United States. Side effects include skin rash and pruritus; drug interactions are unknown. (29) DMSO is available as a gel, liquid, or roll-on.

Boron

The element boron plays a key role in the chemical make-up of bones and joints through its effects on calcium metabolism. In areas of the world where dietary boron intake is usually 1 mg or less per day, the estimated incidence of osteoarthritis ranges from 20 to 70 percent, while in areas of the world where boron intake is 3 to 10 mg per day, the incidence of osteoarthritis is only zero to 10 percent. (32) Evidence from one small, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial (33) suggests that boron supplementation may benefit patients with osteoarthritis.

Other Herbs/Supplements

A recent Cochrane review (34) focusing on osteoarthritis attempted to identify evidence for several herbal products, including tipi, capsaicin, reumalex, and avocado/soybean unsaponifiables. For the most part, this review found only sparse and insufficient studies of these products. However, avocado/soybean unsaponifiables in a 300-mg daily dosage did reduce NSAID use and provide long-term symptomatic relief in two well-done clinical trials of three and six months. Patients with osteoarthritis of the hip appeared to attain a greater degree of benefit. (34)

Nondrug Modalities

Several systematic reviews of RCTs suggest that exercise and physical therapy result in a reduction of disability and pain in patients with osteoarthritis. However, blinding of such trials is problematic, and the participants in these trials may not have been representative of the general population. (35)

A 1997 NIH Consensus Statement (36) on acupuncture listed osteoarthritis as one of the disorders "for which the research evidence is less convincing but for which there are some positive clinical trials." Proponents of acupuncture have argued that proper acupuncture modalities were not used in these trials. Although acupuncture has been promoted as a safe therapy, significant infections have occurred, including human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis, as a result of the use of unsterilized needles. (37)

As shown in in vitro studies, electromagnetic fields stimulate chondrocyte proliferation and increase synthesis of proteoglycan. (38,39) Two recent RCTs (40,41) of pulsed electromagnetic field therapy for knee osteoarthritis showed this treatment to be superior to placebo in reducing symptoms. More research in this area is needed.

The authors indicate that they do not have any conflicts of interest. Source of funding: none reported.

REFERENCES

(1.) Resch KL, Hill S, Ernst E. Use of complementary therapies by individuals with `arthritis'. Clin Rheumatol 1997;16:391-5.

(2.) Barclay TS, Tsourounis C, McCart GM. Glucosamine. Ann Pharmacother 1998;32:574-9.

(3.) Setnikar I, Pacini MA, Revel L. Antiarthritic effects of glucosamine sulfate studied in animal models. Arzneimittelforschung 1991;41:542-5.

(4.) Rindone JP, Hiller D, Collacott E, Nordhaugen N, Arriola G. Randomized, controlled trial of glucosamine for treating osteoarthritis of the knee. West J Med 2000;172:91-4.

(5.) Houpt JB, McMillan R, Wein C, Paget-Dellio SD. Effect of glucosamine hydrochloride in the treatment of pain of osteoarthritis of the knee. J Rheumatol 1999;26:2423-30.

(6.) Delafuente JC. Glucosamine in the treatment of osteoarthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2000;26: 1-11.

(7.) Qiu GX, Gao SN, Giacovelli G, Rovati L, Setnikar I. Efficacy and safety of glucosamine sulfate versus ibuprofen in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Arzneimittelforschung 1998;48:469-74.

(8.) McAlindon TE, LaValley MP, Gulin JP, Felson DT. Glucosamine and chondroitin for treatment of osteoarthritis: a systematic quality assessment and meta-analysis. JAMA 2000;283:1469-75.

(9.) Towheed TE, Anastassiades TP, Shea B, Houpt J, Welch V, Hochberg MC. Glucosamine therapy for treating osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2001;1:CD002946.

(10.) Lopes Vaz A. Double-blind clinical evaluation of the relative efficacy of ibuprofen and glucosamine sulphate in the management of osteoarthrosis of the knee in out-patients. Curr Med Res Opin 1982;8: 145-9.

(11.) Bourgeois P, Chales G, Dehais J, Delcambre B, Kuntz JL, Rozenberg S. Efficacy and tolerability of chondroitin sulfate 1200 mg/day vs chondroitin sulfate 3 3 400 mg/day vs placebo. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 1998;6(suppl A):25-30.

(12.) Leeb BF, Schweitzer H, Montag K, Smolen JS. A metaanalysis of chondroitin sulfate in the treatment of osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol 2000;27:205-11.

(13.) Morreale P, Manopulo R, Galati M, Boccanera L, Saponati G, Bocchi L. Comparison of the antiinflammatory efficacy of chondroitin sulfate and diclofenac sodium in patients with knee osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol 1996;23: 1385-91.

(14.) Kelly GS. The role of glucosamine sulfate and chondroitin sulfates in the treatment of degenerative joint disease. Altern Med Rev 1998;3:27-39.

(15.) Leffler CT, Philippi AF, Leffler SG, Mosure JC, Kim PD. Glucosamine, chondroitin, and manganese ascorbate for degenerative joint disease of the knee or low back: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. Mil Med 1999;164: 85-91.

(16.) McCarty MF. The neglect of glucosamine as a treatment for osteoarthritis-a personal perspective. Med Hypotheses 1994;42:323-7.

(17.) The review of natural products. Drugs Facts and Comparisons. St. Louis, Mo.: Facts and Comparisons, 1996.

(18.) Di Padova C. S-adenosylmethionine in the treatment of osteoarthritis. Review of the clinical studies. Am J Med 1987;83:60-5.

(19.) Bradley JD, Flusser D, Katz BP, Schumacher HR Jr, Brandt KD, Chambers MA, et al. A randomized, double blind, placebo controlled trial of intravenous loading with S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) followed by oral SAM therapy in patients with knee osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol 1994;21:905-11.

(20.) Barcelo HA, Wiemeyer JC, Sagasta CL, Macias M, Barreira JC. Effect of S-adenosylmethionine on experimental osteoarthritis in rabbits. Am J Med 1987;83:55-9.

(21.) Konig B. A long-term (two years) clinical trial with S-adenosylmethionine for the treatment of osteoarthritis. Am J Med 1987;83:89-94.

(22.) Srivastava KC, Mustafa T. Ginger (Zingiber officinale) in rheumatism and musculoskeletal disorders. Med Hypotheses 1992;39:342-8.

(23.) Muller-Fassbender H. Double-blind clinical trial of S-adenosylmethionine versus ibuprofen in the treatment of osteoarthritis. Am J Med 1987;83:81-3.

(24.) Vetter G. Double-blind comparative clinical trial with S-adenosylmethionine and indomethacin in the treatment of osteoarthritis. Am J Med 1987; 83:78-80.

(25). Maccagno A, Di Giorgio EE, Caston OL, Sagasta CL. Double-blind controlled clinical trial of oral S-adenosylmethionine versus piroxicam in knee osteoarthritis. Am J Med 1987;83:72-7.

(26.) Caruso I, Pietrogrande V. Italian double-blind multicenter study comparing S-adenosylmethionine, naproxen, and placebo in the treatment of degenerative joint disease. Am J Med 1987;83:66-71.

(27.) Glorioso S, Todesco S, Mazzi A, Marcolongo R, Giordano M, Colombo B, et al. Double-blind multicentre study of the activity of S-adenosylmethionine in hip and knee osteoarthritis. Int J Clin Pharmacol Res 1985;5:39-49.

(28.) Bliddal H, Rosetzsky A, Schlichting P, Weidner MS, Andersen LA, Ibfelt HH, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled, cross-over study of ginger extracts and ibuprofen in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2000;8:9-12.

(29.) Swanson BN. Medical use of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). Rev Clin Basic Pharm 1985;5:1-33.

(30.) Santos L, Tipping PG. Attenuation of adjuvant arthritis in rats by treatment with oxygen radical scavengers. Immunol Cell Biol 1994;72:406-14.

(31.) Eberhardt R, Zwingers T, Hofmann R. DMSO in patients with active gonarthrosis. A double-blind placebo controlled phase III study [in German]. Fortschr Med 1995;113:446-50.

(32.) Newnham RE. Essentiality of boron for healthy bones and joints. Environ Health Perspect 1994; 102(suppl 7):83-5.

(33.) Travers RL, Rennie GC, Newnham RE. Boron and arthritis: the results of a double-blind pilot study. In: British Society for Nutritional Medicine. Journal of nutritional medicine. Vol 1. Abingdon, Oxfordshire, U.K.: Carfax, 1990:127-32.

(34.) Little CV, Parsons T. Herbal therapy for treating osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2001; 1:CD002947.

(35.) Petrella RJ. Is exercise effective treatment for osteoarthritis of the knee? Br J Sports Med 2000; 34:326-31.

(36.) Acupuncture. NIH Consens Statement 1997;15:1-34.

(37.) Berman BM, Swyers JP, Ezzo J. The evidence for acupuncture as a treatment for rheumatologic conditions. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2000;26:103-15.

(38.) Aaron RK, Ciombor DM, Jolly G. Stimulation of experimental endochondral ossification by low-energy pulsing electromagnetic fields. J Bone Miner Res 1989;4:227-33.

(39.) Baker B, Spadaro J, Marino A, Becker RO. Electrical stimulation of articular cartilage regeneration. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1974;238:491-9.

(40.) Zizic TM, Hoffman KC, Holt PA, Hungerford DS, O'Dell JR, Jacobs MA, et al. The treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee with pulsed electrical stimulation. J Rheumatol 1995;22:1757-61.

(41.) Trock DH, Bollet AJ, Dyer RH Jr, Fielding LP, Miner WK, Markoll R. A double-blind trial of the clinical effects of pulsed electromagnetic fields in osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol 1993;20:456-60.

VINCENT MORELLI, M.D., is assistant professor in the Department of Family Medicine at the Louisiana State University School of Medicine in New Orleans. Dr. Morelli received his medical degree from the University of Southern California (USC) School of Medicine, Los Angeles, Calif. He completed a family practice residency at Whittier/USC and a fellowship in sports medicine and arthroscopy at Jonkoping Hospital, Jonkoping, Sweden. Dr. Morelli is currently the team physician for the New Orleans Brass hockey team, the New Orleans Zephyrs baseball team, the New Orleans Storm soccer team, and the University of New Orleans.

CHRISTOPHER NAQUIN, M.D., is a second-year resident at the Louisiana State University Family Practice Center and the Louisiana State University Medical Center Family Practice Residency Program in Kenner, La. He earned his medical degree from the Louisiana State University School of Medicine.

VICTOR WEAVER, M.D., is a second-year resident at the Louisiana State University Medical Center Family Practice Residency Program. He received his medical degree from the University of Florida College of Medicine, Jacksonville.

Address correspondence to Vincent Morelli, M.D., LSU Health Sciences Center, Family Practice Residency Program, 200 W. Esplanade Ave., Suite 510, Kenner, LA 70065. Reprints are not available from the authors.

COPYRIGHT 2003 American Academy of Family Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2003 Gale Group