Supreme Court Ponders Legality Of Church's Ritual Use Of Hallucinogenic Sacrament

Jeffrey Bronfman was drawn to Brazil's rain forests because of his commitment to ecological preservation.

But on a 1990 trip to help form an environmental association, Bronfman discovered a religion that sparked a spiritual side of his life he had never known. The faith is called O Centro Espirita Beneficiente Uniao do Vegetal (UDV), which in Portuguese means "Central Beneficial Spirit United from the Plants." It would so move him that he would make numerous trips from his home in Santa Fe, N.M., back to Brazil to learn Portuguese and study doctrine.

A few years later, Bronfman, a member of a wealthy family that once owned Seagram's liquor distillery, had become so proficient in Portuguese and knowledgeable of the religion's ways, which intertwines Christianity with indigenous beliefs, that its highest authorities made him a mestre, meaning a member of the church's clergy.

With the UDV's blessing, Bronfman started conducting rituals with a small group of people in Santa Fe and later created a branch of the church there.

Bronfman's efforts to practice his newfound religion, however, would eventually come to a tumultuous halt. A central part of the church's rituals is the use of hoasca tea, which includes a hallucinogenic drug that the federal government has outlawed.

Not long after launching the UDV in Santa Fe, Bronfman found himself in federal court fighting the threat of criminal prosecution pursuant to the Controlled Substances Act. That legal fight has drawn national and international attention and pits two federal laws against one another.

One law is aimed at protecting the free exercise of religion, the other at fighting the spread of illegal drugs. The case has reached the U.S. Supreme Court, where it could produce greater understanding of the breadth of religious liberty in the nation.

UDV members believe hoasca, when used under the guidance of UDV leaders, produces spiritual awakening. Indeed, it was Bronfman's use of the tea in his 1990 trip to Brazil that profoundly affected him.

"It was on that trip thar I first attended a UDV ceremony and drank the tea," Bronfman stated, in an affidavit before a U.S. district court in 2000. "I was very moved and inspired by what I witnessed."

Bronfman said the plants that produce the tea "sprang originally from the graves of revered historical figures and, therefore, embody the spirits of those individuals. The tea enables members to achieve heightened states of spiritual enlightenment."

He explained, "Through the union of the plants (in the ritual preparation of the tea), a sacrament is created that permits the possibility (under the direction of a trained mestre) of actual communion with God."

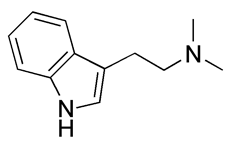

It is the use of the tea, however, that has proven troublesome to federal authorities. Dimethyltryptamine, commonly know as DMT, is the hallucinogenic compound that occurs in the creation of the hoasca.

In May 1999, according to Bronfman, "twenty to thirty armed officers accompanied by local and state police officers" entered UDV's offices and seized a substantial quantity of hoasca. The warrant presented to Bronfman staled that the government officials were also looking for drug paraphernalia.

"It was evident," Bronfman later testified, "that they had no idea we were a church and that the tea, for us, was not a drug, but a religious sacrament."

Bronfman quickly filed suit in federal court citing the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA), a 1993 federal law that forbids government to "substantially burden" the free exercise of religion, unless it can prove a "compelling" interest in doing so.

U.S. District Judge James A. Parker issued a preliminary injunction against the federal government, concluding that officials had failed to satisfy the compelling interest test. The 10th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals on two occasions refused to invalidate Parker's action.

In its second ruling, Circuit Judge Stephanie K. Seymour described the church's case as "unique in many respects because it involves a clash between two federal statutes."

But in a concurring opinion, Seymour decided that the dispute between the church and the federal drug law was "not about enjoining enforcement of the criminal laws against the use and importation of street drugs. Rather, it is about importing and using small quantities of a controlled substance in the structured atmosphere of a bona fide religious ceremony.

"In short," Seymour continued, "this case is about RPRA and the free exercise of religion, a right protected by the First Amendment to our Constitution."

The U.S. Justice Department, then under Attorney General John Ashcroft, now Alberto Gonzales, couldn't disagree more. Federal attorneys asked the U.S. Supreme Court to overturn the 10th Circuit's ruling. This spring, the justices decided to review Gonzales v. O Centro Espirita Beneficiente Uniao Do Vegetal in its next term starting in October.

In urging the high court to take the case, Acting Solicitor General Paul D. Clement argued that the 10th Circuit's decision "has mandated that the federal government open the Nation's borders to the importation, circulation, and usage of a mind-altering hallucinogen and threatens to inflict irreparable harm on international cooperation in combating transnational narcotics trafficking."

Before the lower federal courts, the Justice Department made three arguments: use of hoasca puts the health of UDV members at risk, there is danger that hoasca would be distributed to individuals outside the church and failure to ban the drug would result in breach of the 1971 United Nations Convention on Psychotropic Substances, to which 160 nations, including America, are parties. The Convention bans traffic in certain substances.

All the government's arguments were unpersuasive to Judge Seymour and the majority of the appellate bench.

The religious use of hoasca, according to the UDV's web site, predates the arrival of Europeans in South America in the early 16th century. Anthropologist Marlene Dobkin de Rois told NPR's "The Infinite Mind," that hoasca has been used in South America's Amazon region since "at least 3,000 years ago but up to 8,000 years ago."

Jose Gabriel da Costa, founder of UDV, revived the tea's contemporary religious use in 1961. Today Brazil has about 8,000 UDV adherents. Brazil officially recognizes UDV, and though a member of the UN Convention, exempts hoasca from its controlled substances law. Bronfman says there are at least 130 UDV members in the United States, with congregations in Washington, California, Colorado and Florida.

In his 2000 declaration before the district court, Bronfman said that the UDV conducts regular religious services at 8:00 p.m. on the first and third Saturday of each month and on ten other fixed religious holidays during the year. An example of an annual holiday, Bronfman said, is June 23 when adherents contemplate the life and teachings of John the Baptist. Church doctrine, which includes use of the Ten Commandments, Bronfman says, requires that members in structured religious ceremonies ingest hoasca at least twice monthly.

The services begin with a moment of silent prayer, followed by the mestre leading congregants in a prayer spoken in Portuguese, which translates "May God guide us on the path of light forever and ever. Amen, Jesus." The members then drink the hoasca, church laws are read and explained and the mestre sings a series of "chamadas," which are calls "to encourage the spiritual exercise," Bronfman testified.

Bronfman said that congregants "typically have begun to feel the effects" of the tea by the time the reading of church doctrine is complete. Reportedly the liquid is bitter and not easily consumed. Richard Glen Boire, co-director of the Center for Cognitive Liberty and Ethics, a libertarian-leaning advocacy group, told The New Yorker that the tea "tastes horrendous. Almost everyone who drinks it throws up. Ninety percent of the people who try it will have the most horrendous physical experience that they have ever had in their lives. It's terrifying, but kind of profound, too."

In summer 2002 after the district court conducted a twoweek trial, Judge Parker issued a 60-page opinion concluding that the use of hoasca at UDV religious ceremonies is not dangerous and that the government had not satisfied its burden under the RFRA. He found no evidence that the tea posed a health risk to UDV members or that it was likely to be diverted to non-religious abuse.

Parker's conclusion on the health risks of hoasca came after hearing from 20 witnesses, including a Purdue University professor of medicinal chemistry and molecular pharmacology and a University of California School of Medicine professor of psychiatry.

Justice Department lawyers argue that the professors were "hired" experts, not worthy of belief. In a brief arguing for review of the case before the Supreme Court, Clement maintains that studies of DMT "have documented significant adverse psychological effects arising from ingestion of the substance, such as relapse of depression, intense anxiety and disorientation, and various forms of psychosis."

John Boyd, an attorney for UDV, disagreed, telling the high court that the federal government has unfairly characterized the case. He accused federal authorities of including "fragments of evidence the district court found unpersuasive" and omitting wide swaths of testimony - "including the government's own that showed UDVs sacramental use of hoasca causes no harm and is not likely to be diverted to non-religious use."

Boyd, like Judge Seymour, believes the case ultimately rests on how the high court re-interprets the Religious Freedom Restoration Act. The RFRA was passed by Congress to contain the damage to religious freedom caused by a Supreme Court decision.

In 1990, members of a Native American church in Oregon sued the state seeking an exemption from its drug laws for the sacramental use of peyote, a mildly hallucinogen cactus. In Employment Division v. Smith, Justice Antonin Scalia, writing for the majority, concluded that generally applicable laws that infringe on religious exercise do not always amount to a First Amendment violation.

Smith did not sit well with an array of public interest groups, some who rarely see eye-to-eye on church-state issues. Many of those groups, as well as lawyers, academics and politicians, noted that in two previous cases - Sherbert v. Verner in 1963 and Wisconsin v. Yoder in 1972 - the justices employed a "compelling interest" test to limit government infringements on religious practices.

RFRA was signed into law by President Bill Clinton. In a speech before students and teachers at James Madison High School in Vienna, Va., in 1995, President Clinton, in lauding the RFRA, alluded to the Smith case.

"I've always felt that in order for me to be free to practice my faith in this country," Clinton told the gathering, "I had to let other people be free as possible to practice theirs, and that the government had an extraordinary obligation to bend over backwards not to do anything to impose any set of views on any group of people or to allow others to do so under the cover of law.

But RFRA's constitutional validity isn't rock solid. It was invalidated by the Supreme Court in 1997 as applied to the states. It remains constitutional as applied to federal government laws and actions.

UDV attorneys are pinning their hopes on the law's continuing impact.

"The Congress passed the Religious Freedom Restoration Act in order to reinforce the principles of the free exercise of religion as they existed before the Supreme Court decided the Smith case," Boyd told Church & State.

Boyd is also citing other governmental actions that support his claim. Congress, in 1994, amended the American Indian Religious Freedom Act to require the states to allow Native American church members to use peyotc, which is also regulated by the Controlled Substances Act. The UDV, and several of the 10th Circuit judges, cited that action as undercutting the government's claim that an exemption for hoasca would undermine national and international drug laws.

The UDV lawsuit has also drawn support from conservative religious groups that want to expand the free exercise of religion. Briefs supporting the church were filed by the Christian Legal Society and the National Association of Evangelicals.

Conservative legal voices on the courts have also sided with the church. Tenth Circuit Judge Michael McConnell, wrote a concurring opinion in the November 2004 decision, supporting the UDV position. Neither Congress nor the executive branch, he said, has treated the Controlled Substances Act as precluding "a particularized assessment of the risks involved in a specific sacramental use. Neither should we." (McConnell is a Religious Right favorite, often mentioned as a potential Bush nomination for the Supreme Court.)

The Bush administration, however, believes that in the UDV case, the church's religious practices, at least those related to the use of hoasca, are outweighed by government's duty to heavily regulate drugs.

In their brief at the Supreme Court, Justice Department attorneys, citing federal cases dealing with drug regulation, concluded that, "There can be 'no doubt' that the use of controlled substances and trafficking in those drugs, including DMT, 'creates social harms of the first magnitude,' and that drug abuse is 'one of the greatest problems affecting the health and welfare of our population.'"

Boyd, in an interview with Church & Stale, called the government's claims about the dangers of DMT overblown and said the Justice Department has never been able to proffer evidence strong enough to overcome the religious liberty protections under the RFRA.

"In this case, the government was unable to prove that it had any compelling interests in interfering with the UDVs free exercise of religion," Boyd said. "Under the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, that is the government's burden and it did not carry it.

"Any one who believes that free exercise ought to be protected in this country, regardless of whether they are a religious person or civil libertarian or both, should be rooting for the UDV in this case."

Copyright Americans United for Separation of Church and State Jun 2005

Provided by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights Reserved