Domperidone (Motilium) is a synthetic benzimidazole compound that has had a primary therapeutic benefit as a prokinetic agent for treatment of upper gastrointestinal motility disorders. Domperidone is a peripheral dopamine^sub 2^ receptor (D2; see box on page 330) antagonist. It antagonizes the effects of dopamine-mediated gastric smooth-muscle inhibition through D2 receptors in the gut. In addition it exerts antiemetic properties at the chemoreceptor trigger zone, outside the blood-brain barrier.1-3

Domperidone blocks dopamine-mediated inhibition of prolactin secretion by the anterior pituitary, resulting in increased serum prolactin levels. Domperidone is gaining popularity as a galactagogue (a substance that facilitates milk production). It displays fewer central nervous system (CNS) side effects than does metoclopramide, which has a similar therapeutic profile but penetrates the blood-brain barrier.2,4,5 Domperidone is not currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) so access to this medication in the US is primarily through compounding pharmacies. The purpose of this article is to provide background information for domperidone's use as a galactagogue.

General Pharmacology

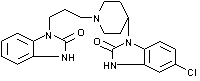

The pharmacocology of domperidone has been reviewed2,3,6-10 elsewhere and is summarized in Table 1. Domperidone is a benzimidazole compound (Figure 1), structurally related to haloperidol and other butyrophenone tranquilizers. It is structurally distinct from metoclopramide and cisapride (benzamides), which together with domperidone have been the three most frequently used prokinetic drugs worldwide. Cisapride was withdrawn from US and Canadian markets in 2000.2,11,12

Domperidone is practically insoluble in water and does not readily cross the blood-brain barrier, reducing CNS and extrapyramidal side effects seen with metoclopramide. The most commonly reported side effects are dry mouth, headache/migraine, diarrhea, abdominal pain and, in nonlactating patients, prolactin-related symptoms (ie, galactorrhea, gynecomastia, breast tenderness, menstrual irregularities). Domperidone is available only in oral dosage forms following reports of arrhythmia, sudden death and cardiac arrest in patients receiving high doses intravenously; the manufacturer withdrew parenteral forms of the drug in 1984.7,9

Domperidone enters human milk but at lower levels, relative to therapeutic dosage, than those reported for metoclopramide.6,13,14 Mean concentrations of domperidone in human milk of 1.2 ng/mL15 and 2.6 ng/mL13 were found during 5 and 4 days, respectively, of treatment with domperidone 30 mg/d. Hale estimates6 a theoretical infant dose through human milk at 0.4 µg/kg/day. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) classifies16 domperidone as "usually compatible with breastfeeding."

Use as a Galactagogue

Rationale

Prolactin and Lactation. Prolactin is a peptide hormone that shares structural homologies with growth hormone. Its primary role is thought to be initiation and maintenance of milk production, but it is known17,18 also to play a role in over 300 cellular functions.

Prolactin activates expression of milk protein genes by binding to its receptor on the surface of milk-producing alveolar cells, with subsequent activation of the Janus family tyrosine kinase/signal transducers and activators of transcription pathway (JAK/STAT pathway). In the classical model,17 the prolactin-receptor complex remains at the cell surface and signal transduction takes place at a distance, through a cascade of phosphorylation of protein kinases and transcription factors. However, recent evidence indicates that prolactin is chaperoned to the nucleus by the peptidyl prolyl isomerase (PPI) cyclophilin B (CypB), where the prolactin/CypB complex can directly modulate the activity of transcription factor Stat5.19

During pregnancy, breast tissue matures and proliferates under the influence of prolactin and other hormones, as scrum prolactin levels rise steadily from prepregnancy levels of 10-25 ng/mL to 200-400 ng/mL at delivery. Milk production is inhibited by progesterone, although colostrum is produced late in pregnancy (lactogenesis I). At delivery, a sharp drop in progesterone levels coupled with high levels of prolactin signal the start of copious milk production, usually between 2 to 4 days postpartum (lactogenesis II). In nonbreastfeeding mothers, serum prolactin levels return to prepregnancy levels within 3 weeks postpartum. In breastfeeding mothers, prolactin levels also drop, but more gradually. Serum prolactin levels correlate with frequency of suckling and remain higher than in prepregnancy throughout lactation.18,20,21

Prolactin is synthesized and secreted by the anterior pituitary. The hypothalamus controls prolactin secretion via dopamine-mediated inhibition. Dopamine is released from nerve terminals of the intrahypothalamic tuberoinfundibular tract and transported via the hypophyseal portal blood to the anterior pituitary, where it activates D2 receptors on lactotrophs and inhibits prolactin release from these cells. Disruption of this axis leads to increased prolactin secretion.1,17

Infant suckling stimulates afferent nerves that cause inhibition of dopamine release by the hypothalamus and a subsequent surge of prolactin from the anterior pituitary. Suckling also stimulates the release of oxytocin from the posterior pituitary, which in turn causes contraction of the myoepithelial cells surrounding milk-producing alveoli, resulting in the milk ejection reflex. Thus, the act of breastfeeding causes surges both in prolactin, necessary for milk production, and in oxytocin, necessary for milk removal.18,20,21

Prolactin remains necessary for milk production throughout lactation, but serum prolactin levels do not correlate with the short-term rate of milk synthesis or milk yield once lactation is established. Instead, the rate of milk synthesis is modulated by the extent of milk removal-the short-term rate of milk synthesis is highest when most of the available milk has been removed. In addition, when the breasts remain full, a locally acting, as yet unidentified, feedback inhibitor of lactation (FIL) inhibits milk production. This ongoing lactation (lactogenesis III) appears to be under autocrine control-milk supply is regulated by the frequency and extent of milk removal from the breasts.18,20,22,23

Domperidone and Prolactin Levels. Domperidone antagonizes dopamine activation of D2 receptors at the anterior pituitary, causing serum prolactin levels to rise. In two studies,24,25 nonpregnant women showed serum prolactin level increases of about 15-fold after single oral doses of domperidone (10 or 20 mg). Women showed a more pronounced rise in serum prolactin than did men (15-fold versus 5-fold). Basal levels of prolactin in both men and women were higher25 after 14 days of domperidone at 30 mg/d [8.1 ng/mL (day 1) versus 24.0 ng/mL (day 14) in women; 4.5 ng/mL versus 10.2 ng/mL, respectively, in men], but the prolactin response in women was not as pronounced as on day 1 of the study [111.0 ng/mL (day 1) versus 53.2 ng/mL (day 14)].

Mean serum prolactin levels were significantly elevated14 in women 2 to 8 days postpartum after a single 20-mg dose of domperidone (255 ng/mL domperidone versus 150 ng/mL placebo; P

A direct relation between serum prolactin levels and occurrence of prolactin-related effects has not been seen26 in patients taking domperidone for gastrointestinal-related symptoms.

Domperidone and Milk Supply. In a placebo-controlled, double-blind trial,15 milk supply and serum prolactin levels increased in 16 mothers of premature infants taking domperidone 30 mg/d over 7 days. Milk production in these mothers had remained low even after extensive lactation counseling (average time for entry into the study was 32 and 33 days after delivery). The group receiving domperidone showed a larger baseline daily volume of milk but also experienced a significantly greater mean increase in milk volume (113 mL baseline, 162 mL during treatment) than did the placebo group (48 mL baseline, 56 mL during treatment), representing a 44.5% and 16.6% increase in milk production, respectively (P

In primiparous mothers whose milk yields 2 weeks after delivery were at least 30% lower than previously described norms, domperidone 30 mg/d for 10 days was associated with significantly increased milk volume [347 mL (day 2) to 673 mL (day 10) domperidone; 335 mL (day 2) to 398 mL (day 10) placebo]. Mean plasma prolactin levels were significantly higher in the domperidone group (169 ng/mL) than in the placebo group (84 ng/mL) by day 2 of the study.27

Protocols

Low Milk Supply. Because milk supply is under autocrine control once lactation is established, the most important factor in improving milk production is frequent and effective removal of milk from the breasts. Before domperidone or another galactagogue is suggested, the mother should first ensure that her baby's latch-on and suckling are effective and that breastfeeding management has been optimized, such as by increasing the frequency of nursing or pumping, discontinuing artificial nipple use and using breast compression to maximize baby's intake of milk.28-29 A board-certified lactation consultant or other knowledgeable lactation specialist can help the mother with breastfeeding techniques and management and work with the prescribing physician who medically supervises the mother's use of domperidone.

Jack Newman, MD, describes clinical experience with domperidone for a decline in milk supply associated with extended pumping for a sick or premature baby in the hospital, birth control pill use or unexplained reasons after lactation has been well-established. He also describes domperidone use by mothers who are trying to reduce reliance on formula supplements.29

Lactation Consultants, Barbara Wilson-Clay and Kay Hoover, describe the use of domperidone or other galactagogues by mothers whose infants show failure to thrive because of down-regulation of milk supply from poor breast emptying.30 They caution,18,31 however, that prolonged engorgement in the early postpartum period without emptying of the breasts causes a down-regulation of milk supply from which some mothers never fully recover, despite aggressive pumping regimens and use of galactagogues. They also describe domperidone's short-term use to help mothers who are protecting their milk supply during infant hospitalization, when stress can also cause down-regulation.

Breast reduction surgery can sever milk ducts, reducing milk production capacity in the breast, or damage nerves, reducing the release of prolactin and oxytocin by the pituitary during breastfeeding. Domperidone or other galactagogues are sometimes suggested as an augmentation to breastfeeding management techniques for increasing milk supply.32

There are no studies addressing optimal dosage of domperidone as a galactagogue. Suggested dosages range from 30 mg/day15 to 80-90 mg/day.29

Induced Lactation, induced lactation is the stimulation of milk production in women who have not undergone a pregnancy. Stimulation of the breasts by infant suckling or pumping is the single most important factor in stimulating milk production, but galactagogues or hormonal treatments have been used to augment these efforts.28

A protocol devised by Jack Newman with Lactation Consultant Lenore Goldfarb is aimed at mothers with advance notice of their baby's arrival. The mother takes a combination estrogen/progesterone birth control pill and domperidone (20 mg 4 times per day) for up to 6 months (modifications of the protocol accommodate mothers who have less advance notice). The contraceptive is discontinued 6 weeks before the baby's arrival (mimicking the drop in progesterone and estrogen at birth), while domperidone is continued and a pumping regimen initiated. This protocol or variations have keen used by over 500 mothers that have been followed clinically by Newman and/or Goldfarb, although not in controlled studies.33

Other Galactagogues

Metoclopramide, another D2 antagonist with gastrokinetic properties, is prescribed as a galactagoguc (off-label in the US).11 Metoclopramide has a lower molecular weight (354) and greater lipid solubility than domperidone, both probably contributing to its greater penetration of the blood-brain barrier.2 Concomitantly, metoclopramide has a higher incidence of CNS and extrapyramidal side effects. Sulpiride and chlorpromazine are antipsychotic drugs that have been shown to increase prolactin levels and milk production, presumably through their action as D2 antagonists, hut adverse maternal side effects such as extrapyramidal reactions and weight gain, and concerns about effects on the infant, limit their utility.5 Both metoclopramide and chlorpromazinc are described by the AAP as "Drugs for Which the Effect on Nursing Infants Is Unknown but May Be of Concern."16 Thyrotrophin-releasing hormone (TRH) has been shown to increase milk: supply and prolactin levels hut is not commonly used in lactation practices.5,18

Oxytocin nasal spray has been used in the past in the US to promote milk letdown, but it does not necessarily increase milk volume; it is no longer commonly prescribed.5,18 Recombinant human growth hormone has been shown to increase milk volume but is not used routinely.3,18,28

Over 400 plant species traditionally used to aid lactation in humans or livestock have been described.34,35 Efficacy of any herbal galactagogue has yet to be demonstrated in controlled studies. Fenugreek in particular has ethnobotanical use from more than one geographic location,34 and Newman36 and Huggins37 describe clinical experience with it. The mechanisms of action of herbal galactagogues have been minimally explored and could potentially involve direct or indirect routes. Plant constituents with prolactin-increasing, estrogenic, oxytocic, tranquilizing or diuretic effects have been identified in a number of galactagogue plant species.34

Summary

Domperidone is gaining popularity as a pharmaceutical galactagogue because of its relatively few side effects (compared to metoclopramide) and lower partitioning into human milk. Mothers using domperidone to enhance milk production should also be working to optimize breastfeeding techniques and management strategies. Because domperidone is not approved by the FDA, compounding pharmacists will continue to play an important role in providing this medication to breastfeeding mothers in the US.

Acknowledgement: The author gratefully acknowledges Sheila Humphrey, International Board Certified Lactation Consultants, for research guidance and helpful discussion about herbal galactagogues.

References

1. Tonini M, Cipollina L, Poluzzi E et al. Clinical implications of enteric and central D2 receptor blockade by antidopaminergic gastrointestinal prokinetics. Aliment Pharmcol Ther 2004; 19(4): 379-390.

2. Barone JA. Domperidone: A peripherally acting dopamine2-receptor antagonist. Ann Pharmacother 1999; 33(4): 429-440.

3. Barone JA. Domperidone: Mechanism of action and clinical use. Hospital Pharmacy 1998; 33(2): 191-197.

4. Henderson A. Domperidone: Discovering new choices for lactating mothers. AWHONN Lifelines 2003; 7(1): 54-60.

5. Gabay MP. Galactagogues: Medications that induce lactation. J Hum Lact2002; 18(3): 274-279.

6. Hale TW. Medications and Mothers' Milk. 10th ed. Amarillo, TX: Pharmasoft; 2002: 230-231.

7. Parfitt K, ed. MARTINDALE: The Complete Drug Reference. 32nd ed. London: Pharmaceutical Press; 1999: 1190-1191.

8. Champion MC. Domperidone. Gen Pharmacol 1988; 19(4): 499-505.

9. Champion MC, Hartnett M, Yen M. Domperidone, a new dopamine antagonist. CMAJ 1986; 135(5): 457-461.

10. Brogden RN, Carmine AA, Heel RC et al. Domperidone: A review of its pharmacological activity, pharmacokinetics and therapeutic efficacy in the symptomatic treatment of chronic dyspepsia and as an antiemetic. Drags 1982; 24(5): 360-400.

11. [No author listed.] Metoclopramide (systemic). Physicians' Desk Reference (electronic version). Greenwood Village, CO: Thomson MICROMEDEX; 2004.

12. [No author listed.] Cisapride (systemic). Physicians' Desk Reference (electronic version). Greenwood Village, CO: Thomson MICROMEDEX; 2004.

13. Hofmeyr GJ, van Iddekinge B. Domperidone and lactation. Lancet 1983; 1(8325): 647.

14. Hofmeyr GJ, van Iddekinge B, Blott JA. Domperidone: Secretion in breast milk and effect on puerperal prolactin levels. Br J Obstet Gynsecol 1985; 92(2): 141-144.

15. da Silva OP, Knoppert DC, Angelini MM et al. Effect of domperidone on milk production in mothers of premature newborns: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. CMAJ 2001; 164(1): 17-21.

16.[No author listed.] Committee on Drugs. American Academy of Pediatrics. The transfer of drugs and other chemicals into human milk. Pediatrics 2001; 108(3): 776-789.

17. Nussey SS, Whitehead SA. The pituitary gland. In: Endocrinology: An Integrated Approach. Oxford: BIOS Scientific Publishers Ltd., 2001.

18. Lawrence RA, Lawrence RM. Breastfeeding: A Guide forthe Medical Profession. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby, Inc., 1999: 65-80, 635-637.

19. Clevenger CV. Nuclear localization and function of polypeptide ligands and their receptors: A new paradigm for hormone specificity within the mammary gland? Breast Cancer Res 2003; 5(4): 181-187.

20. Riordan J, Auerbach KG. Breastfeeding and Human Lactation. 2nd ed. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett Publishers, Inc.; 1999: 98-104.

21. Chao S. The effect of lactation on ovulation and fertility. Clin Perinatol 1987; 14(1):39-50.

22. Daly SE, Hartmann PE. Infant demand and milk supply. Part 2: The short-term control of milk synthesis in lactating women. J Hum Lact 1995; 11(1): 27-37.

23. Daly SE, Hartmann PE. Infant demand and milk supply. Part 1: Infant demand and milk production in lactating women. J Hum Lact 1995; 11(1): 21-26.

24. Brown TE, Fernandes PA, Grant LJ et al. Effect of parity on pituitary prolactin response to metoclopramide and domperidone: Implications for the enhancement of lactation. J Soc Gynecol Investig 2000; 7(1): 65-69.

25. Brouwers JR, Assies J, Wiersinga WM et al. Plasma prolactin levels after acute and subchronic oral administration of domperidone and of metoclopramide: A cross-over study in healthy volunteers. Clin Endocrinol(Qxf) 1980; 12(5): 435-440.

26. Cann PA, Read NW, Holdsworth CD. Galactorrhea as side effect of domperidone. Br Med J1983; 286(6375): 1395-1396.

27. Petraglia F, De Leo V, Sardelli S et al. Domperidone in defective and insufficient lactation. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 1985; 19(5): 281-287.

28. Mohrbacher N, Stock J. The Breastfeeding Answer Book. 3rd ed. Schaumburg, IL: La Leche League International; 2003: 168-171, 394-397.

29. Newman J. Domperidone. Handouts 19a and 19b. 2003. Available at: www.breastfeedingonline.com/domperidone.shtml. Accessed March 26, 2004.

30. Wilson-Clay B, Hoover K. The Breastfeeding Atlas. 2nd ed. Austin, TX: LactNews Press; 2002: 67, 81-85, 118-119.

31. Daly SE, Kent JC, Owens RA et al. Frequency and degree of milk removal and the short-term control of human milk synthesis. Exp Physiol 1996; 81(5): 861-875.

32. West D. Defining Your Own Success: Breastfeeding After Breast Reduction Surgery. Schaumburg, IL: La Leche League International; 2001: 193-196.

33. Goldfarb L, Newman J. The Protocols for Induced Lactation: A Guide for Maximizing Breastmilk Production. 2002. Available at: www.asklenore.info/breastfeeding/inducedjactation/intro.html. Accessed March 26, 2004.

34. Bingel AS, Farnsworth NR. Higher plants as potential sources of galactagogues. In: Wagner H, Hikino HN, Farnsworth NR, eds. Econ Med Plant Res. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1994; 6: 1-54.

35. Humphrey S. The Nursing Mother's Herbal. Minneapolis, MN: Fairview Press; 2003: 105-139, 308-322.

36. Newman J. Miscellaneous treatments. Handout 24. 2003. Available at: www.breastfeedingonline.com/24.html. Accessed April 29, 2004.

37. Muggins KE. Fenugreek: One remedy for low milk production. Medela Rental Round-up 1998; 15(1): 16-17. Available at: www.breastfeeding.org/articles/fenugreek.html. Accessed April 27, 2004.

38. Gether U. Uncovering molecular mechanisms involved in activation in G protein-coupled receptors. Endocr Rev 2000; 21(1): 90-113.

39. Civelli O. Molecular biology of the dopamine receptor subtypes. In: Bloom FE, Kupfer DJ. Psychoparmacology: The Fourth Generation of Progress; New York, NY: Raven Press; 1995: 155-161.

40. Strange PG. Dopamine receptors. Tocris Reviews No. 15. October 2000. Linked through www.tocris.com/Tsframeset.html. Accessed February 15, 2004.

41. Kuhar MJ, Couceyro PR, Lambert PD. Catecholamines. In: Siegel GJ, Agranoff BW, Albers RW et al, eds. Basic Neurochemistry: Molecular, Cellular and Medical Aspects. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 1998: 243-261.

42. Scarselli M, Novi F, Schallmach E et al. D2/D3 dopamine receptor heterodimers exhibit unique functional properties. J Biol Chem 2001; 276(321:30308-30314.

Lisa M. Albright, PhD

Austin, Texas

Address correspondence to: Lisa M. Albright, PhD, at lmalbr@alum.mit.edu

Copyright International Journal of Pharmaceutical Compounding Sep/Oct 2004

Provided by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights Reserved