Acute bronchitis is one of the top 10 conditions for which patients seek medical care. Physicians show considerable variability in describing the signs and symptoms necessary to its diagnosis. Because acute bronchitis most often has a viral cause, symptomatic treatment with protussives, antitussives, or bronchodilators is appropriate. However, studies indicate that many physicians treat bronchitis with antibiotics. These drugs have generally been shown to be ineffective in patients with uncomplicated acute bronchitis. Furthermore, antibiotics often have detrimental side effects, and their overuse contributes to the increasing problem of antibiotic resistance. Patient satisfaction with the treatment of acute bronchitis is related to the quality of the physician-patient interaction rather than to prescription of an antibiotic. (Am Fam Physician 2002;65:2039-44, 2046. Copyright[C] 2002 American Academy of Family Physicians.)

Acute bronchitis, one of the most common diagnoses in ambulatory care medicine, accounted for approximately 2.5 million visits to U.S. physicians in 1998.(1) This condition consistently ranks as one of the top 10 diagnoses for which patients seek medical care, with cough being the most frequently mentioned symptom necessitating office evaluation.(1) In the United States, treatment costs for acute bronchitis are enormous: for each episode, patients receive an average of two prescriptions and miss two to three days of work.(2)

Even though acute bronchitis is a common diagnosis, its definition is unclear. The diagnosis is based on clinical findings, without standardized diagnostic signs and sensitive or specific confirmatory laboratory tests.(3) Consequently, physicians exhibit extensive variability in diagnostic requirements and treatment. Antibiotic therapy is used in 65 to 80 percent of patients with acute bronchitis,(4,5) but a growing base of evidence puts this practice into question. This article examines the diagnosis and treatment of acute bronchitis in otherwise healthy, nonsmoking patients, with a focus on symptomatic therapy and the role of antibiotics in treatment.

Pathophysiology and Etiology

Acute bronchitis was originally described in the 1800s as inflammation of the bronchial mucous membranes. Over the years, this inflammation has been shown to be the result of a sometimes complex and varied chain of events. An infectious or noninfectious trigger leads to bronchial epithelial injury, which causes an inflammatory response with airway hyperresponsiveness and mucus production.(6) Selected triggers that can begin the cascade leading to acute bronchitis are listed in Table 1.(3,7,8)

TABLE 1

Selected Triggers of Acute Bronchitis

Viruses: adenovirus, coronavirus, coxsackievirus, enterovirus, influenza virus, parainfluenza virus, respiratory syncytial virus, rhinovirus

Bacteria: Bordatella pertussis, Bordatella parapertussis, Branhamella catarrhalis, Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, atypical bacteria (e.g., Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydia pneumoniae, Legionella species)

Yeast and fungi: Blastomyces dermatitidis, Candida albicans, Candida tropicalis, Coccidioides immitis, Cryptococcus neoformans, Histoplasma capsulatum

Noninfectious triggers: asthma, air pollutants, ammonia, cannabis, tobacco, trace metals, others Information from references 3, 7, and 8.

Acute bronchitis is usually caused by a viral infection.(9) In patients younger than one year, respiratory syncytial virus, parainfluenza virus, and coronavirus are the most common isolates. In patients one to 10 years of age, parainfluenza virus, enterovirus, respiratory syncytial virus, and rhinovirus predominate. In patients older than 10 years, influenza virus, respiratory syncytial virus, and adenovirus are most frequent.

Parainfluenza virus, enterovirus, and rhinovirus infections most commonly occur in the fall. Influenza virus, respiratory syncytial virus, and coronavirus infections are most frequent in the winter and spring.(7)

Signs and Symptoms

Classifying an upper respiratory infection as bronchitis is imprecise. However, studies of bronchitis and upper respiratory infections often use the same constellation of symptoms as diagnostic criteria.(10-14)

Cough is the most commonly observed symptom of acute bronchitis. The cough begins within two days of infection in 85 percent of patients.(15) Most patients have a cough for less than two weeks; however, 26 percent are still coughing after two weeks, and a few cough for six to eight weeks.(15) When a patient's cough fits this general pattern, acute bronchitis should be strongly suspected.

Although most physicians consider cough to be necessary to the diagnosis of acute bronchitis, they vary in additional requirements. Other signs and symptoms may include sputum production, dyspnea, wheezing, chest pain, fever, hoarseness, malaise, rhonchi, and rales.(16) Each of these may be present in varying degrees or may be absent altogether. Sputum may be clear, white, yellow, green, or even tinged with blood. Peroxidase released by the leukocytes in sputum causes the color changes; hence, color alone should not be considered indicative of bacterial infection.(17)

Physical Examination and Diagnostic Studies

The physical examination of patients presenting with symptoms of acute bronchitis should focus on vital signs, including the presence or absence of fever and tachypnea, and pulmonary signs such as wheezing, rhonchi, and prolonged expiration. Evidence of consolidation must be absent.(7) Fever may be present in some patients with acute bronchitis. However, prolonged or high-grade fever should prompt consideration of pneumonia or influenza.(7)

Recommendations on the use of Gram staining and culture of sputum to direct therapy for acute bronchitis vary, because these tests often show no growth or only normal respiratory flora.(6,7) In one recent study,(8) nasopharyngeal washings, viral serologies, and sputum cultures were obtained in an attempt to find pathologic organisms to help guide treatment. In more than two thirds of these patients, a pathogen was not identified. Similar results have been obtained in other studies. Hence, the usefulness of these tests in the outpatient treatment of acute bronchitis is questionable.

Despite improvements in testing and technology, no routinely performed studies diagnose acute bronchitis. Chest radiography should be reserved for use in patients whose physical examination suggests pneumonia or heart failure, and in patients who would be at high risk if the diagnosis were delayed.(7) Included in the latter group are patients with advanced age, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, recently documented pneumonia, malignancy, tuberculosis, and immunocompromised or debilitated status.(7)

Office spirometry and pulmonary function testing are not routinely used in the diagnosis of acute bronchitis. These tests are usually performed only when underlying obstructive pathology is suspected or when patients have repeated episodes of bronchitis. Pulse oximetry may play a role in determining the severity of the illness, but results do not confirm or rule out bronchitis, asthma, pneumonia, or other specific diagnoses.

Treatment

PROTUSSIVES AND ANTITUSSIVES

Because acute bronchitis is most often caused by a viral infection, usually only symptomatic treatment is required. Treatment can focus on preventing or controlling the cough (antitussive therapy) or on making the cough more effective (protussive therapy).(18)

Protussive therapy is indicated when coughing should be encouraged (e.g., to clear the airways of mucus). In randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies of protussives in patients with cough from various causes, only terbutaline (Brethine), amiloride (Midamor), and hypertonic saline aerosols proved successful.(19) However, the clinical utility of these agents in patients with acute bronchitis is questionable, because the studies examined cough resulting from other illnesses. Guaifenesin, frequently used by physicians as an expectorant, was found to be ineffective, but only a single 100-mg dose was evaluated.(19) Common preparations (e.g., Duratuss) contain guaifenesin in doses of 600 to 1,200 mg.

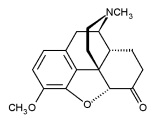

Antitussive therapy is indicated if cough is creating significant discomfort and if suppressing the body's protective mechanism for airway clearance would not delay healing. Studies have reported success rates ranging from 68 to 98 percent.(18) Antitussive selection is based on the cause of the cough. For example, an antihistamine would be used to treat cough associated with allergic rhinitis, a decongestant or an antihistamine would be selected for cough associated with postnasal drainage, and a bronchodilator would be appropriate for cough associated with asthma exacerbations. Nonspecific antitussives, such as hydrocodone (e.g., in Hycodan), dextromethorphan (e.g., Delsym), codeine (e.g., in Robitussin A-C), carbetapentane (e.g., in Rynatuss), and benzonatate (e.g., Tessalon), simply suppress cough.(18) Selected nonspecific antitussives and their dosages are listed in Table 2.(20)

BRONCHODILATORS

Acute bronchitis and asthma have similar symptoms. Consequently, attention has recently been given to the use of bronchodilators in patients with acute bronchitis. Although relatively few studies have examined the efficacy of oral or inhaled beta agonists, one study(21) found that patients with acute bronchitis who used an albuterol metered-dose inhaler were less likely to be coughing at one week, compared with those who received placebo.

ANTIBIOTICS

Because of increasing concerns about antibiotic resistance, the practice of giving antibiotics to most patients with acute bronchitis has been questioned.(22,23) Clinical trials on the effectiveness of antibiotics in the treatment of acute bronchitis have had mixed results and rather small sample sizes. Attempts have been made to quantify and clarify data from the studies (Table 3).(24-28) Although these reviews and meta-analyses used many of the same studies, they examined different end points and reached slightly different conclusions. One analysis(25) showed that antibiotic therapy provided no improvement in patients with acute bronchitis, whereas others, including the Cochrane review,(28) showed a slight beneficial effect; however, problems with antibiotic side effects were similar.

Regardless of the end points evaluated in each study, one fact was consistent: improvement occurred in the vast majority of patients who were not treated with antibiotics. In addition, the patients diagnosed with acute bronchitis who also had symptoms of the common cold and had been ill for less than one week generally did not benefit from antibiotic therapy.(28)

None of the studies included newer macrolides or fluoroquinolones. Studies on the use of these antibiotics in the treatment of acute bronchitis are in progress.

Alternatives to Antibiotics

Patients often expect antibiotic therapy for uncomplicated acute bronchitis. However, patient satisfaction does not depend on receiving an antibiotic. Instead, it is related to the quality of the physician-patient visit.

Physicians should make sure that they explain the diagnosis and treatment of acute bronchitis, and provide realistic expectations about the clinical course. Patients should expect to have a cough for 10 to 14 days after the visit. They need to know that antibiotics are probably not going to be beneficial and that treatment with these drugs is associated with significant risks and side effects. It is helpful to refer to acute bronchitis as a "chest cold."

When determining an optimal treatment protocol for acute bronchitis, physicians need to consider the issue of antibiotic resistance. Although the mechanisms leading to antibiotic resistance are complex, previous antibiotic use is a major risk factor.(27,29) Studies have shown that decreasing the use of antibiotics within a community can reduce the prevalence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria.(30,31)

An algorithm for the treatment of acute bronchitis is provided in Figure 1.(15,32)

The authors indicate that they do not have any conflicts of interest. Sources of funding: none reported.

REFERENCES

(1.) Slusarcick AL, McCaig LF. National hospital ambulatory medical care survey: 1998 outpatient department summary. Hyattsville, Md.: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, 2000; DDHS publication no. (PHS) 2000-1250/0-0520.

(2.) Oeffinger KC, Snell LM, Foster BM, Panico KG, Archer RK. Diagnosis of acute bronchitis in adults: a national survey of family physicians. J Fam Pract 1997;45:402-9.

(3.) Hueston WJ, Mainous AG III. Acute bronchitis. Am Fam Physician 1998;57:1270-6,1281-2.

(4.) Gonzales R, Steiner JF, Sande MA. Antibiotic prescribing for colds, upper respiratory tract infections, and bronchitis by ambulatory care physicians. JAMA 1997;278:901-4.

(5.) Mainous AG III, Zoorob RJ, Hueston WJ. Current management of acute bronchitis in ambulatory care: the use of antibiotics and bronchodilators. Arch Fam Med 1996;5:79-83.

(6.) Treanor JJ, Hayden FG. Viral infections. In: Murray JF, ed. Textbook of respiratory medicine. 3d ed. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2000:929-84.

(7.) Blinkhorn RJ Jr. Upper respiratory tract infections. In: Baum GL, ed. Textbook of pulmonary diseases. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven, 1998:493-502.

(8.) Boldy DA, Skidmore SJ, Ayres JG. Acute bronchitis in the community: clinical features, infective factors, changes in pulmonary function and bronchial reactivity to histamine. Respir Med 1990;84:377-85.

(9.) Marrie TJ. Acute bronchitis and community acquired pneumonia. In: Fishman AP, Elias JA, eds. Fishman's Pulmonary diseases and disorders. 3d ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1998:1985-95.

(10.) Scherl ER, Riegler SL, Cooper JK. Doxycycline in acute bronchitis: a randomized double-blind trial. J Ky Med Assoc 1987;85:539-41.

(11.) Franks P, Gleiner JA. The treatment of acute bronchitis with trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole. J Fam Pract 1984;19:185-90.

(12.) Williamson HA Jr. A randomized, controlled trial of doxycycline in the treatment of acute bronchitis. J Fam Pract 1984;19:481-6.

(13.) Brickfield FX, Carter WH, Johnson RE. Erythromycin in the treatment of acute bronchitis in a community practice. J Fam Pract 1986;23:119-22.

(14.) Dunlay J, Reinhardt R, Roi LD. A placebo-controlled, double-blind trial of erythromycin in adults with acute bronchitis. J Fam Pract 1987;25:137-41.

(15.) Chesnutt MS, Prendergast TJ. Lung. In: Tierney LM, ed. Current medical diagnosis & treatment, 2002. 41st ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002:269-362.

(16.) Mufson MA. Viral pharyngitis, laryngitis, croup and bronchitis. In: Goldman L, Bennett JC, eds. Cecil Textbook of medicine. 21st ed. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2000:1793-4.

(17.) Chodosh S. Acute bacterial exacerbations in bronchitis and asthma. Am J Med 1987;82(4A):154-63.

(18.) Irwin RS, Boulet LP, Cloutier MM, Fuller R, Gold PM, Hoffstein V, et al. Managing cough as a defense mechanism and as a symptom. A consensus panel report of the American College of Chest Physicians. Chest 1998;114(2 suppl managing): S133-81.

(19.) Irwin RS, Curley FJ, Bennett FM. Appropriate use of antitussives and protussives. A practical review. Drugs 1993;46:80-91.

(20.) Physicians' desk reference. 56th ed. Montvale, N.J.: Medical Economics, 2002.

(21.) Hueston WJ. Albuterol delivered by metered-dose inhaler to treat acute bronchitis. J Fam Pract 1994; 39:437-40.

(22.) Snow V, Mottur-Pilson C, Gonzales R. Principles of appropriate antibiotic use for treatment of acute bronchitis in adults. Ann Intern Med 2001;134: 518-20.

(23.) Arroll B, Kenealy T. Antibiotics for acute bronchitis [Editorial]. BMJ 2001;322:939-40.

(24.) MacKay DN. Treatment of acute bronchitis in adults without underlying lung disease. J Gen Intern Med 1996;11:557-62.

(25.) Fahey T, Stocks N, Thomas T. Quantitative systematic review of randomised controlled trials comparing antibiotic with placebo for acute cough in adults. BMJ 1998;316:906-10.

(26.) Smucny JJ, Becker LA, Glazier RH, McIsaac W. Are antibiotics effective treatment for acute bronchitis? A meta-analysis. J Fam Pract 1998;47:453-60.

(27.) Bent S, Saint S, Vittinghoff E, Grady D. Antibiotics in acute bronchitis: a meta-analysis. Am J Med 1999;107:62-7.

(28.) Smucny J, Fahey T, Becker L, Glazier R, McIsaac W. Antibiotics for acute bronchitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000;(4):CD000245.

(29.) Gonzales R, Barrett PH Jr, Crane LA, Steiner JF. Factors associated with antibiotic use for acute bronchitis. J Gen Intern Med 1998;13:541-8.

(30.) Stephenson J. Icelandic researchers are showing the way to bring down rates of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. JAMA 1996;275:175.

(31.) Seppala H, Klaukka T, Vuopio-Varkila J, Muotiala A, Helenius H, Lager K, et al. The effect of changes in the consumption of macrolide antibiotics on erythromycin resistance in group A streptococci in Finland. Finnish Study Group for Antimicrobial Resistance. N Engl J Med 1997;337:441-6.

(32.) Hueston WJ. Antibiotics: neither cost effective nor "cough" effective. J Fam Pract 1997;44:261-5.

Members of various family practice departments develop articles for "Practical Therapeutics." This article is one in a series coordinated by the Department of Family Medicine at Ohio State University College of Medicine and Public Health, Columbus. Guest editor of the series is Doug Knutson, M.D.

DOUG KNUTSON, M.D., is assistant professor in the Department of Family Medicine at Ohio State University School of Medicine and Public Health, Columbus, where he earned his medical degree. Dr. Knutson completed a family practice residency at Riverside Methodist Hospital, Columbus, Ohio.

CHAD BRAUN, M.D., is clinical assistant professor and associate residency director in the Department of Family Medicine at Ohio State University School of Medicine and Public Health. Dr. Braun received his medical degree from the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine and completed a family practice residency at Riverside Methodist Hospital.

Address correspondence to Doug Knutson, M.D., Department of Family Medicine, Ohio State University College of Medicine and Public Health, 2231 N. High St., Columbus, OH 43201 (knutson.1@osu.edu). Reprints are not available from the authors.

COPYRIGHT 2002 American Academy of Family Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2002 Gale Group