Family physicians (FPs) face significant challenges in the management of obese patients, who often experience serious comorbidities and increased risk of mortality. Bariatric surgery represents an effective option for many morbidly obese patients. In addition to weight loss, this surgery has been associated with a dramatic improvement in diabetes, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and obstructive sleep apnea.

Yet, clinicians who want to consider this option for their patients face challenges: Who should be considered a candidate for bariatric surgery? How does an FP effectively collaborate with the bariatric surgeon? How should complications be managed? What is the responsibility of each health care provider regarding long-term patient management? This case study examines these important issues.

PRESENTATION OF THE CASE

Mrs RF is a 52-year-old woman who has type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia. Her height is 5'2" and her weight is 274 lb, with a calculated body mass index (BMI) of 50 kg/[m.sup.2].

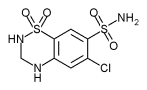

Her current medications include glyburide (10 mg QD), metformin (1000 mg BID), simvastatin (40 mg QD), lisinopril (20 mg QD), and hydrochlorothiazide (12.5 mg QD).

Physical examination reveals an obese woman in no apparent distress. Her blood pressure is 138/89.

Results of her serum chemistries are significant for a normal thyroid-stimulating hormone, hemoglobin [A.sub.1c] of 8.2, total cholesterol of 247 mg/dL, and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) of 171 mg/dL. She has a normal complete blood count, as well as normal electrolyte levels and renal function.

The patient reports that she has struggled with her weight since her teens. She has had minor success with dietary weight loss but has consistently regained weight when returning to her baseline diet. She has read about weight loss surgery and is interested in this option.

Concerns for the clinician: Patient selection

Mrs RF meets the basic indications for weight loss surgery, based on consensus criteria from the National Institutes of Health. These include BMI [greater or equal to] 40 kg/[m.sup.2] or BMI [greater or equal to] 35 kg/[m.sup.2] associated with high risk comorbidities, including sleep apnea, cardiomyopathy, Pickwickian syndrome, type 2 diabetes, joint disease, and body size problems that interfere with ambulation and employment. (1) At initial consultation, the patient does not exhibit contraindications, such as poor overall medical condition, unresolved substance abuse, depression, or unwillingness to modify her lifestyle. However, further investigation is warranted. Profound and lifelong changes in dietary habits must be implemented postsurgery; therefore, for Mrs RF to be a suitable candidate, she must be psychologically stable and thoroughly informed about the procedure and its long-term effects.

For preoperative clearance and informed consent, Mrs RF needs to meet with the bariatric surgeon to whom the FP refers her, as well as other individuals who will help her understand the procedure. Qualified bariatric surgeons typically work with a team that includes a licensed nutritionist, who will review the dietary and nutritional issues associated with the procedure, and a psychologist, who will provide a formal psychologic evaluation. Additionally, bariatric centers usually offer educational sessions; these will help Mrs RF learn about weight loss surgery from individuals who have had the operation.

DISCUSSION OF THE PROCEDURE WITH THE PATIENT

Mrs RF's physician discusses with her the risks and benefits associated with the procedure. Bariatric surgery is associated with a loss of up to 80% of excess weight. Patients who undergo gastric procedures with a malabsorptive component are less likely to regain weight than are those who have purely restrictive procedures, such as gastric banding. (2) Overall, weight loss surgery provides long-lasting results, if patients adhere to dietary and nutritional recommendations. Very rarely does weight loss continue to the point that patients become underweight.

Health benefits associated with surgery

The FP reviews with Mrs RF the growing body of outcome data that show the effect of weight loss surgery and weight loss reduction on obesity-related mortality, as described below.

Weight loss surgery and type 2 diabetes. A recent study found that Roux-en-Y gastric bypass improved fasting glucose levels in all patients, with normalization of hemoglobin [A.sub.1C] in 83% of the population with type 2 diabetes. Persons with the shortest duration and mildest degree of type 2 diabetes and those with the greatest weight loss were more likely to achieve greater benefits)

Weight loss surgery, dyslipidemia, and hypertension. A recta-analysis of bariatric surgery outcomes suggests that weight loss surgery improves both hypercholesterolemia and hypertriglyceridemia in at least 70% of patients, Improvement was greatest in patients undergoing a procedure with a malabsorptive component. Median cholesterol was lowered by an average of 33.2 mg/dL and LDL by 29.3 mg/dL. (4)

This meta-analysis also revealed that weight loss surgery demonstrated an improvement in hypertension in 78% of patients. Remarkably, the majority (61.7%) of patients experienced resolution of their hypertension.

Weight loss surgery, asthma, and sleep apnea. The association of obesity with asthma and sleep apnea was seen in a 2004 study where 30% of candidates for weight loss surgery had symptoms of asthma and nearly one third experienced sleep apnea. Postsurgery, improvement in asthma was reported in 79% of patients. Of the 29 patients who used continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy for sleep apnea prior to surgery, 25 patients discontinued CPAP use. (5)

REFERRAL TO THE BARIATRIC SURGEON

Mrs RF remains highly interested in weight loss surgery. Her FP refers her to a surgeon who has performed a large number of procedures and is associated with a bariatric center identified by the American Society for Bariatric Surgery as a "Center of Excellence." (The American College of Surgeons will soon offer a similar designation.) Such accreditation can provide a level of comfort for referring FPs.

The bariatric surgeon's team conducts a thorough medical, nutritional, and psychologic evaluation. The surgeon describes available surgical options for weight loss. These can be broadly divided into 4 main categories: malabsorptive, malabsorptive and restrictive, restrictive, and neither malabsorptive nor restrictive.

Malabsorptive procedures performed include biliopan-creatic diversion and duodenal switch. The common feature of these procedures is that separate enteric and biliopancreatic limbs are created, allowing food, bile, and pancreatic juices to travel separately in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract until they reach a distal common channel. This prevents full absorption of nutrients.

Malabsorptive and restrictive procedures combine the malabsorptive component with gastric restriction. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass involves the construction of a small (15-20 mL) gastric pouch with a partial jejunal bypass. The gastric and enteric limbs then join to form a common channel for digestion.

Restrictive procedures include vertically banded gastroplasty and gastric banding. These operations rely purely on restricting the stomach to limit dietary intake. They do not alter the physiology of digestion.

Other options. Recent developments currently undergoing clinical trials include gastric and vagal pacing. This strategy seeks to provide a sense of satiety, leading to reduced caloric intake without either gastric restriction or small-bowel bypass components. The FDA will review these procedures to determine their place in the armamentarium of bariatric surgeons.

Discussion of risks of bariatric surgery

The bariatric surgeon discusses the risks associated with surgery. Immediate major postoperative complications include anastomotic leak, intestinal obstruction, GI hemorrhage, pneumonia, and atelectasis. A recently published large series revealed an anastomotic leak rate of 3.2%. Risk factors for leak included age, male sex, and the presence of sleep apnea. (6) Rates of anastomotic leak diminish as a surgeon's experience increases. (7) One meta-analysis suggested that the rate of bowel obstruction is approximately 3% and the incidence of GI bleeding is 2%. (8)

Perioperative mortality for bariatric procedures is between 1% and 2%; the vast majority of complications occur in the first 14 days after surgery. The 30-day mortality rate in 1 study was 1.9%. (9) This appears to be typical of many modern series.

COURSE OF TREATMENT

After examination and discussion, the bariatric surgeon recommends a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, and surgery is scheduled. Before and after the operation, the FP receives communication from the bariatric surgeon in the form of letters and telephone calls. The patient is discharged on postoperative day 2 after she had tolerated her diet.

POSTOPERATIVE FOLLOW-UP

During the immediate postoperative period, Mrs RF is advised to call her surgeon with any concerns. Over 90% of serious complications (sepsis, anastomotic leaks, internal hernias and obstructions) occur in this time frame. If Mrs RF were to call her FP, the surgeon should be contacted promptly.

Both the FP and the bariatric surgeon emphasize to Mrs RF that nausea and emesis are frequently experienced side effects and fall into 2 categories: 1) Benign nausea and emesis are often caused by overeating or eating the wrong food. Symptoms resolve quickly with changes in eating behavior. Good nutritional counseling preoperatively and prior to discharge often prevents this problem. 2) Progressive nausea and emesis may signal serious complications and, during the immediate postdischarge period, warrant emergent evaluation.

Mrs RF calls her FP on postoperative day 6 complaining of intermittent emesis. A review of her diet reveals that she has been compliant. She has consumed 2 oz pureed/strained food per hour with frequent intake of water or liquids totalling 48 oz per 24 hours. She is also receiving approximately 70 g of protein per day, as recommended.

COLLABORATIVE POSTOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

The FP and bariatric surgeon discuss the possibility that Mrs RF's emesis may result from complications, such as an anastomotic leak. Symptoms include tachycardia, fever, hypotension, shoulder pain, and tachypnea. Any suspicion of leak mandates thorough investigation, including either abdominal computed topography (CT) or an esophagram. Additional etiologies of postoperative emesis include anastomotic edema or small-bowel obstruction. Anastomotic stenosis may also occur within the first 3 months after the operation and usually responds to endoscopic dilatation. (10)

To ascertain the cause of Mrs RF's symptoms, her FP obtains an esophagram, which reveals edema at the gastrojejunostomy. Emesis resolves with conservative management: eating slowly and remaining hydrated. On follow-up, she does well.

Medications after surgery

Weight loss surgery may affect a patient's GI physiology. The presence of 1 or more anastomoses also must be taken into consideration. In general, patients who have had a procedure with a malabsorptive component should avoid non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs because of the risk of marginal ulceration. Absorption of time-release medications also may be altered. Medication should not be administered in sustained-release formulations because of altered intestinal absorption following procedures with a malabsorptive component.

Effects on glucose metabolism

Six weeks after the procedure, Mrs RF calls her FP to report fatigue in the late afternoons. This pattern of fatigue is associated with finger-stick blood glucose levels of 45 to 50 mg/dL. At this juncture, it is not unusual for a patient to have lost in excess of 20 lb, and studies have now shown that the resolution of hyperglycemia often precedes significant weight loss. (6) Typically, oral hypoglycemic agents should be reduced or discontinued in the immediate postoperative period in anticipation of improving glucose tolerance. Patients may be optimally managed with the use of low-dose sliding scale insulin in the postoperative period until their type 2 diabetes mellitus improves or resolves. Mrs RF's oral hypoglycemic agents are discontinued with the resolution of hypoglycemia.

Six-month follow-up

At her 6-month follow-up appointment, Mrs RF has lost 75 lb and continues to do well. She has noted resolution of hyperglycemia. In addition, her FP observes normalization of her blood pressure and discontinues hydrochlrothiazide. Laboratory testing confirms adequate nutritional status; this testing should be performed at 6-month intervals and at any time symptoms suggesting nutritional deficiencies occur.

Complication 8 months after surgery

Approximately 8 months after surgery, Mrs RF calls her FP to complain that her hair appears to be thinning. Weight loss operations, especially those with a malabsorptive component, significantly alter a patient's nutritional requirements. Common nutritional deficiencies include protein, iron, folate, calcium, and vitamins [B.sub.12], A, D, E, and [K.sup.11] Patients who have undergone procedures with a malabsorptive component require life-long supplementation of these nutrients. Both the FP and bariatric surgeon must maintain a high index of suspicion for the presence of nutritional abnormalities. Typical indications of protein deficiency are alopecia and alterations in finger and toe nails. Even without those markers of protein deficiency, patients should be evaluated with a detailed physical exam and laboratory tests for vitamin levels, especially vitamin [B.sub.12] and folate, and serum protein levels, specifically albumin and the short turnover proteins transferin and retinol-binding protein. Discussion concerning her diet reveals that Mrs RF's protein intake has fallen below the recommended 70 g/d. Her alopecia resolves with an increase in her protein intake to the recommended 70 g/d.

One year follow-up

One year after surgery, Mrs RF weighs 158 lb. She is happy with the results of her weight loss surgery and the benefits of decreased hypertension and resolution of her type 2 diabetes mellitus. In addition, she reports that she has more energy and less difficulty ambulating.

CONCLUSIONS

Weight loss after bariatric surgery ranges from 30% to 90% of excess body weight, and the results are life-changing for many patients. Loss of excess weight tends to be greatest after procedures that contain a malabsorptive component in addition to a restrictive component. (2)

Mrs RF's course is typical of many patients who have undergone weight loss surgery. Although complications can occur, the benefits outweigh the risks for many patients. In addition, many of the complications that occur postoperatively are managed relatively easily by FPs in collaboration with bariatric surgeons.

REFERENCES

(1.) NIH Conference. Gastrointestinal surgery for severe obesity. Consensus Development Conference Panel. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115:956-961.

(2.) Weber M, Muller MK, Bucher T, et al. Laparoscopic gastric bypass is superior to laparoscopic gastric banding for treatment of morbid obesity. Ann Surg. 2004;240:975-982.

(3.) Schauer PR, Burguera B, Ikramuddin S, et al. Effect of laparoscopic Roux-en Y gastric bypass on type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ann Surg. 2003;238:467-485.

(4.) Buchwald H, Avidor Y, Braunwald E, et al. Bariatric surgery: a systematic review and recta analysis. JAMA. 2004;292:1724-1737.

(5.) Simard B, Turcotte H, Marceau P, et al. Asthma and sleep apnea in patients with morbid obesity: outcome after bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2004;14:1381-1388.

(6.) Fernandez AZ Jr, DeMaria EJ, Tichansky DS, et al. Experience with over 3,000 open and laparoscopic bariatric procedures: multivariate analysis of factors related to leak and resultant mortality. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:193-197.

(7.) DeMaria EJ, Sugerman HJ, Kellum JM, Meador JG, Wolfe LG. Results of 281 consecutive total laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypasses to treat morbid obesity. Ann Surg. 2002;235:650-645.

(8.) Podnos YD, Jimenez JC, Wilson SE, Stevens CM, Nguyen NT. Complications after laparoscopic gastric bypass: a review of 3464 cases. Arch Surg. 2003;138:957-961.

(9.) Maggard MA, Shugarman LR, Suttorp M, et al. Meta-analysis: surgical treatment of obesity. Ann Intern Med. 2005; 142:547-559.

(10.) Schwartz ML, Drew RL, Roiger RW, Ketover SR, Chazin-Caldie M. Stenosis of the gastroenterostomy after laparoscopic gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2004;14:484-491.

(11.) Bloomberg RD, Fleishman A, Nalle JE, Herron EM, Kini S. Nutritional deficiencies following bariatric surgery: what have we learned? Obes Surg. 2005;15:145-154.

Sarah D. Pritts, MD David R. Fischer, MD Timothy A. Pritts, MD, PhD

From the Departments of Family Medicine (S. Pritts) and Surgery (D. Fischer and T. Pritts), University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, Cincinnati, Ohio.

* Address for correspondence:

Sarah D. Pritts, MD University of Cincinnati College of Medicine Department of Family Medicine P.O. Box 670582 Cincinnati, OH 45267-0582 (e-mail: prittssd@fammed.uc.edu)

COPYRIGHT 2005 Dowden Health Media, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2005 Gale Group