Gefitinib is a new drug that was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in May 2003 for non-small cell cancer of the lung refractory to first- and second-line therapy. It is regarded as a rather safe drug with common adverse effects that include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, rash, acne, and dry skin. However, it was reported in Japan to be associated with interstitial pneumonitis (2%-3% of subjects), presumably as a manifestation of a hypersensitivity reaction. The Food and Drug Administration studied this in US patients and found only a 0.3% occurrence and a slightly less than 0.1% mortality due to interstitial pneumonitis. To our knowledge, there has not been an association with fulminant myocarditis or acute myocarditis. We report the case of a 71-year-old man who died as a result of fulminant myocarditis 1 week after starting to take this new class of agent, gefitinib. On the basis of his medical history and our findings, we feel it necessary to consider hypersensitivity myocarditis related to gefitinib the probable cause of death.

(Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2005;129:1044-1046)

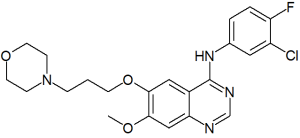

Gefitinib is a new drug that was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in May 2003 for the treatment of non-small cell cancer of the lung refractory to first- and second-line therapy.1 It is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, and its effectiveness against lung cancer is based on evidence that it inhibits the tyrosine kinase associated with the epidermal growth factor.1 Response to gefitinib was recently associated with specific mutations in the tyrosine kinase domain of the epidermal growth factor receptor.2 It is regarded as a rather safe drug with common adverse effects that include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, rash, acne, and dry skin. However, it was reported in Japan to be associated with interstitial pneumonitis (2%-3% of subjects), presumably as a manifestation of a hypersensitivity reaction.1 The Food and Drug Administration studied this in US patients and found only a 0.3% occurrence and a slightly less than 0.1% mortality due to interstitial pneumonitis.1 To our knowledge, it has not been associated with fulminant myocarditis or acute myocarditis.

We report the case of a 71-year-old man who died as a result of fulminant myocarditis 1 week after beginning treatment with this new class of agent, gefitinib. On the basis of his medical history and our findings, we feel it necessary to consider hypersensitivity myocarditis related to gefitinib the probable cause of death.

REPORT OF A case

The decedent was a 71-year-old man who presented at the University of California-Los Angeles Medical Center emergency department complaining of a 4-day history of nonbloody loose stools and lightheadedness. His blood pressure was 79/27 mm Hg, his pulse rate was 132/min, his respiratory rate was 24/min, and his temperature was 35.8°C. Proceeding with a presumptive diagnosis of sepsis, he was treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics, vasopressors, and dopamine. He was intubated and admitted to the medical intensive care unit. A chemistry panel was remarkable for the following values: sodium, 142 mEq/L; potassium, 2.6 mEq/L; chloride, 124 mEq/L; bicarbonate, 10 mEq/L; serum urea nitrogen, 55 mg/dL (39 mmol/L); and creatinine, 3.8 mg/dL (340 µmol/L). Calcium was markedly low at 3.2 mg/dL (0.8 mmol/L) with magnesium at 1.0. A chest x-ray did not show any obvious infiltrates. His electrocardiogram demonstrated atrial fibrillation and a left bundle branch block. Despite intensive care support, he died in the emergency department approximately 6 hours after initial presentation.

His recent medical history was significant for a diagnosis of non-small cell carcinoma along with a suspicious enlarged lymph node in the right neck detected by a positron emission tomographic scan. He was scheduled for surgery, but, because of his anxiety about his diagnosis, his oncologist decided to begin treatment with gefitinib, an oral tyrosine kinase inhibitor, less than 2 weeks prior to the surgery. He took the drug for 4 days and experienced the onset of nonbloody loose stools. After 2 days of diarrhea, he complained to his oncologist about his symptoms. On the advice of his oncologist, he discontinued the gefitinib. However, his symptoms persisted for 2 more days, prompting his return to the emergency department.

AUTOPSY FINDINGS

On external examination, cyanosis was clearly present and severe. The pericardium contained 130 mL of serous fluid. The pericardium showed no areas with fibrosis. The heart appeared large and weighed 800 g. The left ventricular wall was hypertrophie and measured 2.9 cm in thickness (reference,

The most significant autopsy finding was the extensive inflammatory infiltrate in the myocardium, along with numerous foci of myocyte necrosis, suggestive of myocarditis. The immediate cause of death was fulminant myocarditis.

No organisms were cultured from his blood or urine in the emergency department, and no organisms were cultured from his splenic tissue or urine at autopsy. Serologie studies for coxsackie A and B virus were not consistent with acute infection. A polymerase chain reaction analysis performed on formalin-fixed cardiac tissue failed to demonstrate myocardial infection with enteroviruses or adenovirus.

COMMENT

The clinical manifestations of myocarditis range from an asymptomatic state, with the presence of myocarditis inferred only by the finding of transient electrocardiographic ST-segment abnormalities, to a fulminant condition with arrhythmias, heart failure, and death. In some patients, myocarditis simulates acute myocardial infarction, with chest pain, electrocardiographic changes, and elevated serum levels of myocardial enzymes.3

Diagnosing myocarditis is not a simple task. The signs and symptoms can be nonspecific, as can be the abnormalities discovered with routine tests such as complete blood cell counts, erythrocyte sedimentation rates, elevated creatinine levels, electrocardiograms, and echocardiograms. Endomyocardial biopsy is considered the gold standard for diagnosis. Identifying the etiology can be as difficult as diagnosing the illness. Certain parasites and bacteria can be detected in an endomyocardial biopsy, but those cases are unusual in the United States. Positive viral cultures and increases in titers can be suggestive of a particular virus but are not proof of cause for myocarditis. A polymerase chain reaction analysis that demonstrates the presence of viral RNA or DNA is considered sufficient proof that a particular virus caused the illness.4 It has been shown that a polymerase chain reaction analysis from formalin-fixed tissue can positively identify viral etiologies in some cases.5 The noninfectious causes of acute myocarditis can typically be identified only as a potential etiology on the basis of the patient's history and temporal relation to the exposure. In many cases, the etiology is unknown.

In light of the absence of other etiologies and the temporal relationship between the use of this drug and the onset of illness, gefitinib must be considered a possible cause of the hypersensitivity myocarditis in this patient. Only by follow-ups of the patients exposed to this drug will this relationship be proven.

References

1. Evans T. Highlights from the Tenth World Conference on Lung Cancer. Oncologist. 2004:9:232-238.

2. Lynch T], Bell DW, Sordella R, et al. Activating mutation in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness to non-small-cell responsiveness to Cefitinib. N Engl I Med. 2004:350:2129-2139.

3. Feldman AM, McNamara D. Medical progress: myocarditis. N Engl I Med. 2000;343:1388-1398.

4. Tracy S, Wiegand V, McManus B, et al. Molecular approaches to enteroviral diagnosis in idiopathic cardiomyopathy and myocarditis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990; 15:1688-1694.

5. Griffin L, Kearney D, et al. Analysis of formalin-fixed and frozen myocardial autopsy samples for viral genome in childhood myocarditis and dilated cardiomyopathy with endocardial fibroelastosis using polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Cardiovasc Pathol. 1995:4:3-11.

Jeft S. Truell, MD; Michael C. Fishbein, MD; Robert Figlin, MD

Accepted for publication April 1, 2005.

From the Departments of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine (Drs Truell and Fishbein) and Oncology (Dr Figlin), David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California-Los Angeles.

The authors have no relevant financial interest in the products or companies described in this article.

Reprints: )eff S. Truell, MD, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, David Ceffen School of Medicine at UCLA, A7-149 Center for Health Sciences, 10833 Le Conte Ave, Los Angeles, CA 90095 (e-mail: jtruell@ucla.edu).

Copyright College of American Pathologists Aug 2005

Provided by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights Reserved