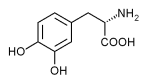

The dopamine precursor levodopa is the most common treatment for Parkinson's disease. Some researchers have recently proposed using dopamine receptor agonists as the initial treatment for Parkinson's disease, because using levodopa early in the course of the disease is believed to cause dyskinesias and motor fluctuations. The Parkinson Study Group conducted a randomized, controlled trial to compare levodopa with pramipexole, a nonergoline dopaminergic agonist.

While previous placebo studies have shown a benefit to treatment with pramipexole, this is the first head-to-head comparison of the two medications. Patients were included in the trial if they had had Parkinson's disease for fewer than seven years and were at least 30 years of age. Those who had taken levodopa or a dopaminergic agonist in the preceding two months were excluded. At the time of enrollment, each patient required dopaminergic antiparkinsonian therapy and could be at Hoehn and Yahr stage I, II or III.

Patients were randomized to receive pramipexole (escalating to a dosage of 1.5 mg per day, given in three equal doses) or carbidopa/ levodopa (escalating to a dosage of 75/300 mg per day, also given in three equal doses). Those who required additional treatment increased their dosage to 3.0 or 4.5 mg of pramipexole per day or 112.5/450 mg or 150/600 mg of carbidopa/levodopa per day. By week 11, all patients were taking one of these daily dosages. From week 11 through month 23.5, patients with worsening disabilities were given open-label carbidopa/levodopa as needed.

The primary outcome measure was the time from randomization to the appearance of wearing off (the perception of loss of mobility, usually closely related to the timing of the medication), dyskinesias (abnormal involuntary movement, not related to the timing of the medication) or on-off fluctuations (sudden, unpredictable shifts between mobility and immobility). Other outcomes measured were scores on various instruments used for rating the progression of Parkinson's disease and patients' quality of life.

The study included 301 patients. In the pramipexole group, 15.1 percent of patients withdrew before the end of the study, compared with 12.7 percent in the carbidopa/levodopa group. More than one half (53 percent) of those in the pramipexole group needed supplemental levodopa during the study, compared with 39 percent in the levodopa group. By month 23.5, primary end points (wearing off, dyskinesias or on-off fluctuations) occurred in 28 percent of the pramipexole group and 51 percent of the levodopa group. In addition, more end points occurred in the patients taking levodopa, but the improvements in Parkinson's disease rating scales were significantly greater in the levodopa group than in the pramipexole group. Quality of life was also better in the patients receiving levodopa. Side effects (somnolence, hallucinations and peripheral edema) were significantly more common in the patients taking pramipexole than in the patients taking levodopa.

The Parkinson Study Group concludes that pramipexole, when used as initial treatment in patients with early Parkinson's disease, is better than levodopa at decreasing the development of certain dopaminergic motor complications. Specifically, the number needed to treat is four or five patients over two years to prevent one additional complication. However, the features of Parkinson's disease were more successfully treated with levodopa than with pramipexole, even when levodopa was added to the pramipexole later in the trial. Until further studies are done, it is reasonable to individualize a patient's treatment based on the relative risk-benefit ratio of pramipexole (favorable dopaminergic motor complication profile) versus levodopa (favorable antiparkinsonian profile).

2000;284:1931-8.

COPYRIGHT 2001 American Academy of Family Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2001 Gale Group