Approximately 15% to 25% of family practice patients have concerns about sexual function and are most comfortable discussing these issues with their family physician. While many physicians have avoided this topic in the past, citing lack of knowledge and skill, the family practice setting is ideal for a preliminary evaluation of sexual dysfunction and treatment for certain etiologies. This especially is true for changes in sexual function secondary to medication effects. This article provides basic guidelines designed to assist physicians in evaluating the effects of medications and other substances on sexual function. Also included are lists of medications known or suspected to have adverse effects on sexual function. Physicians are encouraged to address the sexual concerns of their patients and to incorporate these guidelines and the medication lists into their evaluation.

KEY WORDS. Family practice; sex disorders; drugs; drugs, non-prescription; street drugs; substance abuse. (J Fam Pract 1997; 44:33-43)

It is estimated that 15% to 25% of patients seen in family practice have concerns about sexual function.[1,2] In addition, the majority of patients report feeling most comfortable discussing these issues with their family physician, and expect that their physician will provide advice or treatment.[3] Historically, many physicians have avoided discussing sexual concerns, even when a problem is suspected, citing lack of knowledge and skills as a common reason.[4] While it is true that some of the sexual disorders likely to present in family practice settings will require referral for psychological counseling or specialist treatment, others can be successfully diagnosed and treated in the family practice setting.[5] This especially is true for cases involving medication-related changes in sexual function.

Over 1.5 billion prescriptions are written every year in the United States, which amounts to about six prescriptions per person.[6] Over two thirds of physician office visits result in one or more new prescriptions being written.[6] In addition, numerous non-prescription medications, homeopathic remedies, illicit drugs, and other substances (eg, tobacco and alcohol) likely to have an impact on physiological function are commonly used by patients seen in family practice settings. As a result, most family practice physicians can assume that many of their patients will be taking or will have recently taken medications or other substances.

Several reasons exist for focusing on the effects of these substances when assessing a patient's concerns about sexual function. Primarily, many of the most commonly prescribed medications have been suspected or implicated in the development or exacerbation of sexual dysfunctions.[7,8] Second, a medication change is often the simplest intervention, and may save the patient significant time, money, and emotional distress. Third, when multiple causative factors contribute to the disorder, removing one contributing cause (ie, medication) may restore sexual function to an acceptable level. Fourth, patients who suspect that their medications are causing a sexual disorder may make medication changes on their own if their physician does not address this issue.[9] Finally, referral for psychological treatment for a sexual problem will be ineffective or only partially effective when medications are contributing to the disorder. Consequently, when evaluating sexual disorders, it is imperative to determine the history of medication and other substance use and determine the role these factors may be playing in the disorder.[10]

While some medications are well documented to cause disruption of sexual function, controlled research is sparse for the majority of medications and substances implicated in the etiology of sexual disorders.[11] Most articles present anecdotal evidence or case reports.[12] Many medications cited in articles are referenced only in medication inserts, or no reference is provided. Often, the exact type of dysfunction (eg, erectile disorder, delayed orgasm) is omitted, with terms such as "sexual dysfunction" or "sexual difficulties" substituted. While a few larger studies exist, there is some question as to the accuracy of such data. Reports of erectile disorder can vary from 10% to 26% within the same sample, depending on whether the subjects fill out a self-report or are questioned directly.[13] Even direct questioning may not elicit accurate reporting. Patients completing confidential questionnaires at home are almost twice as likely to report difficulty obtaining erections as patients questioned directly in their physician's office.[14] Such data suggest that the social stigma attached to sexual disorders creates significant underreporting, and may make results from even well-controlled studies questionable. In spite of these limitations, physicians need a starting point for directing assessment and treatment.

In an effort to provide this starting point, the following is a discussion of prescription medications and other substances that have been cited as possibly having side effects that adversely affect sexual function. The accompanying tables also list the most commonly cited side effects, as well as the relative likelihood that the side effect will occur. In light of the factors discussed above, it is impossible to provide exact figures in many cases. Instead, an effort has been made to approximate the likelihood of disorders occurring with different medications. Given the number of articles used in the compilation of the tables, the references for each medication have been omitted.(*)

PRESCRIPTION MEDICATION EFFECTS

While many prescription medications have been implicated in disorders of sexual desire, arousal, and orgasm, medications used to treat hypertension and psychiatric disorders are most frequently cited as contributing to these dysfunctions. In family practice, sexual disorders attributable to these types of medications will be encountered most frequently.

ANTIHYPERTENSIVE MEDICATIONS

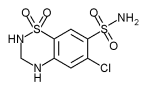

The majority of antihypertensive medications have been implicated in sexual disorders.[13] Some, however, are more likely than others to cause specific problems (Table 1). For example, diuretics (such as chlorthalidone, hydrochlorothiazide, and spironolactone),[15,18] central antiadrenergic agents (eg, clonidine, methyldopa, reserpine),[19,22] and guanethidine[23] are commonly cited as causing erectile disorder. Guanethidine has also been associated with disorders of desire and ejaculation.[24] On the other hand, beta blockers, with the exception of propranolol,[25,26] are less likely to cause erectile problems, but can cause disorders of desire in as many as half of the patients taking them.[27] Of the most commonly used classes of antihypertensives, ACE inhibitors (eg, captopril, enalapril, lisinopril) may be least likely to cause disruptions in sexual function." In addition, minoxidil, hydralazine, prazosin, and furosemide rarely cause sexual side effects, although hydralazine and prazosin have been associated with priapism in case reports.

(*) Case report(s), package insert, or uncertain frequency; (**) infrequent side effect; (***) frequent side effect; (***) very frequent side effect.

Note: Medications and their accompanying side effects that have been cited fiequently as causing sexual disorders are in bold type.

PSYCHIATRIC MEDICATIONS

Psychiatric medications (Table 2) also commonly affect sexual function.[26] Antidepressants, almost without exception, cause changes in sexual response. The tricyclic antidepressants (eg, amitriptyline, amoxapine, clomipramine, desipramine, nortriptyline, protriptyline) have frequently been associated with erectile disorder and can cause a delayed or absent orgasmic response.[29,30] The newer serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), such as fluoxetine and sertraline, while initially touted as lacking sexual side effects, are now frequently cited as causing delayed orgasm. This side effect is so universal that clinicians have used these medications to successfully delay orgasm in patients complaining of premature ejaculation.[31] For depressed patients not complaining of premature ejaculation, however, this side effect can be very distressing and may exacerbate depressive symptoms if not identified and addressed. In addition, as there is no disorder in women comparable to premature ejaculation, it is unlikely that delay in orgasm in women will be seen as a beneficial side effect. Case reports of erectile disorder with SSRIs have also been noted. Finally, trazodone, while not associated with impairment in erection, ejaculation, or orgasm, has been reported to cause priapism.[32]

(*) Case report(s), package insert, or uncertain frequency; (**) nfrequent side effect; (***) frequent side effect; (****) very frequent side effect.

NOTE: Medications and their accompanying side effects that have been cited frequently as causing sexual disorders are in bold type.

Antipsychotic medications, without exception, have the potential for disrupting sexual response (eg, thioridazine, chlorpromazine).[26] Common side effects include erectile disorder and delay of ejaculation and orgasm (Table 3), although desire disorders have also been reported.[12] While the evidence is less conclusive, other psychiatric medications may alter specific components of sexual response. For example, anxiolytics, including the benzodiazepines, may interfere with the ability to attain orgasm.[33,34] Buspirone and several antipsychotic medications have been cited as occasionally causing priapism.[23,35] Lithium and monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitors may impair sexual desire and erectile function.[36,37]

(*) Case report(s), package insert, or uncertain frequency; (**) infrequent side effect; (***) frequent side effect; (****) very frequent side effect.

Note: Medications and their accompanying side effects that have been cited frequently as causing sexual disorders are in bold type.

In short, virtually all antipsychotic and antidepressant medications, as well as a variety of other psychotropic medications, can cause disruptions in sexual function. Many patients may not report these symptoms to their physician, as they may attribute them to their psychiatric disorders, such as lack of sexual desire in a depressed patient. If unaddressed, such symptoms may have a significant impact on self-esteem and may exacerbate the psychiatric condition. Therefore, it is imperative that the physician determine whether a dysfunction exists, assess whether the dysfunction is a side effect of medication, and formulate alternative therapies.

OTHER PRESCRIPTION MEDICATIONS

Many other prescription medications in diverse therapeutic classes are frequently cited as causing sexual dysfunctions. These include carbamazepine,[38] cimetidine,[39] clofibrate,[40] danazol[41] digoxin,[42] disulfiram,[43] ketoconazole,[44] and niacin,[45] to name just a few. These and other miscellaneous medications are listed in Table 4, along with specific side effects and estimated incidences.

(*) Case report(s), package insert, or uncertain frequency; (**) infrequent side effect; (***) frequent side effect; (****) very frequent side effect.

Note: Medications and the accompanying side effects that have been cited frequently as causing sexual disorders are in bold type.

ILLICIT DRUGS, NONPRESCRIPTION MEDICATION, AND OTHER SUBSTANCE EFFECTS

Illicit drugs should not be overlooked in evaluating sexual disorders (Table 5). While physicians know the detrimental effects alcohol can have on sexual function, many patients still believe alcohol will improve sexual function, and they may increase alcohol consumption in response to sexual difficulties. Chronic alcohol abuse may cause hormonal alterations and permanent damage to circulatory and nervous systems,[10,19] so determining whether there is a history of alcohol abuse, as well as current use, is also important. In addition, major and minor tranquilizers, cocaine, and even cigarettes[46,47] have been implicated in sexual disorders. So-called designer drugs (eg, MDMA, "ecstasy") have been less extensively studied, but have been implicated in changes in sexual response and function.[48] Many of these drugs may be overlooked by the patient as a potential cause of his sexual difficulty, as many of these drugs are believed to improve sexual performance by reducing inhibitions, delaying ejaculation, and so on. Any drug that decreases inhibitions and delays ejaculation is likely to have the potential to alter physiological responses necessary for effective sexual function. Although acute effects may enhance sexual function, chronic effects are typically detrimental.[11]

(*) Case report(s), package insert or uncertain frequency; (**) infrequent side effect; (***) frequent side effect; (****) very frequent side effect.

Note: Medications and their accompanying side effects that have been cited frequently as causing sexual disorders are in bold type

In addition to illicit drugs, nonprescription medications and homeopathic remedies also may cause or contribute to sexual dysfunction, albeit rarely (Table 6). These include common medications such as diphenhydramine (Benadryl)[49] and newer nonprescription medications such as naproxen (Aleve).[50] The use of herbal products should also be questioned, since many of these "all natural" products contain pharmacologically active ingredients. Again, patients are not likely to associate these substances with changes in sexual function. It is imperative that physicians be aware of the possible effects of these substances and structure their interview accordingly.

(*) Case report(s), package insert, or uncertain frequency; (**) infrequent side effect; (***) frequent side effect; (****) very frequent side effect.

Note: Medications and their accompanying side effects that have been cited frequently as causing sexual disorders are in bold type.

GUIDELINES FOR ASSESSMENT OF MEDICATION EFFECTS

The presentation of medication-related disorders is often similar to disorders caused by physiological factors. That is, they are likely to be consistent across time and situations, whereas disorders with psychogenic causes are likely to be situation specific. A woman who lubricates and climaxes during masturbation but not with her partner is not likely suffering the side effects of medication. Similarly, a male patient who reports regular morning erections of good rigidity and good erections during masturbation, but no erections or insufficient erections with a partner, is most likely experiencing a psychological problem.

Medication effects, however, may mimic a psychogenic problem in two ways. First, it is possible for medications to have transient effects on sexual function. For example, antihypertensive medications may cause a disruption of sexual function for a few hours after ingestion. A patient who takes one of these medications in the morning may report poor erections with his partner following ingestion but good erections masturbating at other times of the day and good morning erections before taking medication. This patient can be encouraged to modify the timing of his sexual activities, or an alternative dosing schedule may be tried. Second, medication-induced sexual disorders do not typically develop gradually as organic disorders typically do. For example, a patient who reports sudden onset of erectile disorder with a new partner may be diagnosed with a psychogenic disorder. However, if this patient began taking a new medication between relationships, it is possible that the sudden onset is caused by the medication, not the anxiety inherent in a new relationship.

Temporal factors also play a significant role in identifying the contribution of medication to sexual disorders. If a patient is taking a medication known to cause erectile disorder, and he reports an erectile disorder, it may seem likely that the medication is contributing to the disorder. However, if the erectile disorder predates the initiation of the medication, it is unlikely that the medication caused the disorder. Similarly, if a patient has been taking the medication for many years with no change in dose and reports a sexual disorder of recent onset, the medication is unlikely to be the primary cause.

Changes in medication regimens also should be assessed. Medications or doses are regularly changed in response to changes in patient status, such as poor control of hypertension. These changes can be keys to determining the contribution of the medication to the reported sexual symptoms. For example, a client may report that she has taken the same medication for 10 years, and the sexual disorder did not develop until 1 year ago. If the onset of the disorder coincided with an increased dosage of this medication, it may still be the primary cause of the disorder.

On the other hand, if a disorder persists over time, even with repeated changes in medication, it is unlikely that the medication is the primary cause. While many medications can cause sexual disorders, it is unlikely that different medications will cause identical problems in the same patient.[51] Therefore, if a sexual dysfunction has remained consistent despite dose or medication changes, it is unlikely that the medication alone is maintaining the dysfunction. As an example, a patient reported that his erectile disorder started shortly after he began taking medication for high blood pressure. Subsequent changes in medication and ultimately discontinuation of pharmacotherapy did not return erectile function. In this case, the patient was not initially aware of the potential sexual dysfunction side effect of the medication, and did not attribute the disorder to the medication. Instead, he attributed the disorder to anxiety about his new relationship. In essence, the medication "created" performance anxiety that was sufficient to maintain the erectile disorder even after the medication was changed. In this case, reassuring the patient that the medication caused the dysfunction contributed greatly to the cure. This example also illustrates the need to evaluate medications taken around the time of the onset of the disorder, even if these are not the medications being taken at the time of the evaluation.

TREATMENT

Treatment for pharmacologically induced sexual disorders must be approached with some caution. Suggesting to a patient that a medication is the cause of a sexual dysfunction may contribute to nonadherence to the medication regimen. In many cases, for example, patients with hypertension and psychoses, control of the disease or symptoms may outweigh the need for restoration of sexual function. In the patient's mind, however, the opposite is often true. If a patient suspects a medication is contributing to a sexual disorder, he or she is likely to stop taking it.[9] Therefore, it is critical that the physician rule out other possible causes before suggesting a pharmacological cause. In addition, it is crucial for the physician to review with the patient the benefits of medication and the risk of abruptly stopping treatment. The patient should be reassured that if the medication is implicated in the disorder, steps will be taken to identify alternative treatment that will effectively treat the medical condition while simultaneously relieving the sexual problem.

Although identifying possible pharmacological causes may be straightforward, determining effective alternatives may be difficult. For example, as previously discussed, the majority of hypertensive medications have been reported to contribute to sexual disorders, so alternatives are limited. By using the information included in this paper and sound clinical judgment, clinicians can often find successful and therapeutically effective alternatives. When possible, the physician may choose to stay within the same therapeutic class, thereby minimizing disruption to the medication regimen. In other cases, a change in medication class may be unavoidable or more appropriate. For example, central antiadrenergic agents and most diuretic medications may cause erectile disorder, so switching to another medication within the same class may not alleviate the symptom. In these cases, switching to a medication class less likely to cause a problem with sexual function (eg, an ACE inhibitor) may be simpler, more efficient, and less frustrating for the patient.

Finally, removing the effects of a medication may not restore sexual function. As mentioned previously, changes in sexual function will typically produce significant anxiety, which may maintain a disruption in sexual function even after the primary cause has been removed. In these cases, simple reassurance by the physician may be sufficient to restore confidence and sexual function. If not, referral to a qualified mental health professional is indicated.

(*) A complete list of references, including a table with references cited for each medication, is available from the first author on request.

REFERENCES

[1.] James B, Lord DJ. Human sexuality and medical education. Lancet 1976; 2:560-3.

[2.] Tanner LA, Hoff R, Carmichael LP. Teaching sex education and counseling for the primary physician. South Med J 1976; 69:1591-4.

[3.] Matteson GN, Armstrong R, Kimes HM. Physician education in human sexuality. J Fam Pract 1984; 19:683-4.

[4.] Broekman CPM, Van Der Werff Ten Bosch JJ, Slob AK. An investigation into the management of patient with erection problems in general practice. Int J Impotence Res 1994; 6:67-72.

[5.] Courtenay M. Sex problems in practice: what can a general practitioner do? BMJ 1981; 282:873-4.

[6.] Woosley RL, Flockhart D. A case for the development of Centers for Education and Research in Therapeutics (C.E.R.T). Pharmacy Week 1995; 4(23):1-3.

[7.] Hubbard JR, Levenson JL, Patrick GA Psychiatric side effects associated with the ten most commonly dispensed prescription drugs: a review. J Fam Pract 1991; 33:177-89.

[8.] Soyka LF, Mattison DR. Prescription drugs that affect male sexual functioning. Drug Therapy 1981; August:46-58.

[9.] Watts RJ. Sexual functioning, health beliefs, and compliance with high blood pressure medications. Nurs Res 1982; 31:278-83.

[10.] Kaplan HS. The evaluation of sexual disorders: psychological and medical aspects. New York, NY: Brunner/Mazel, 1984.

[11.] Segraves RT, Segraves KB. Aging and drug effects on male sexuality. In: Rosen RC, Leiblum SR, eds. Erectile disorders: assessment and treatment. New York, NY: The Guifford Press, 1992.

[12.] Colvin CL, Ryan ML. Drug induced sexual dysfunction. Micromedex 1996; 89:1-16.

[13.] Prichard BNC, Johnston A, Hill I. Bethanidine guanethidine and methyldopa in treatment of hypertension: a within-patient comparison. BMJ 1968; 1:135.

[14.] Bulpitt CJ, Dollery CT. Side effects of hypotensive agents evaluated by a self-administered questionnaire. BMJ 1973; 3:485-90.

[15.] Chang SW, Fine R, Siegel D, Chesney M, Black D, Hulley SB. The impact of diuretic therapy on reported sexual function. Arch Intern Med 1991; 151:2402-8.

[16.] Stessman J, Ben-Ishay D. Chlorthalidone-induced impotence. BMJ 1980; 281:714.

[17.] Hogan MJ, Wallin JD, Bauer RM. Antihypertensive therapy and male sexual dysfunction. Psychomatics 1980; 21:234-7.

[18.] Caminos-Torres R, Ma L, Snyder PJ. Gynecomastia and semen abnormalities induced by spironolactone in normal men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1977; 45:255-60.

[19.] Buffum J: Pharmasexology the effects of drugs on sexual function. A review. J Psychoactive Drugs 1982; 14:544.

[20.] Hodge RH, Harward MP, West MS, Krongaard-DeMong L, Kowal-Neeley MB. Sexual function of women taking antihypertensive agents: a comparative study. J Gen Intern Med 1991; 6:290-4.

[21.] Boyden TW, Nugent CA, Oligara T. Reserpine hydrochlorothiazide and pituitary-gonadal hormones in hypertensive patients. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1980; 17:329-32.

[22.] Alexander WD, Evans JI. Side effects of methyldopa. Br Med J 1975; 2:501.

[23.] Veterans Administration Cooperative Study Group on Antihypertensive Agents. Multiclinic controlled trial of bethanidine and guanethidine in severe hypertension. Circulation 1977; 55:519-25.

[24.] McMahon FG. Management of essential hypertension. New York, NY: Furtura Publishing, 1978:194.

[25.] Burnett WC, Chahine RA. Sexual dysfunction as a complication of propranolol therapy in men. Cardiovasc Med 1979; 4:811-5.

[26.] Medical Research Council Working Party on Mild to Moderate Hypertension. Adverse reactions to bendrofluazide and pro pranolol for the treatment of mild hypertension. Lancet 1981; 2:53942.

[27.] Mann KV, Abbott EC, Gray JD, Thiebaux HJ, Belzer KG. Sexual dysfunction with beta-blocker therapy: more common than we think? Sexuality and Disability 1982; 5(2):67-77.

[28.] Segraves RT Sexual side effects of psychiatric drugs. Int J Psychiatry Med 1988; 18:243-52.

[29.] Monteiro WO, Noshirvani HF, Marks IM, Lelliott PT. Anorgasmia from clomipramine un obsessive-compulsive disorder. Br J Psychiatry 1987; 151:107.

[30.] Cooper-Smartt JD, Rodham R. A technique for surveying the side-effects of tricyclic drugs with reference to reported sexual effects. J Int Med Res 1973; 1:473.

[31.] Balon R. Antidepressants in the treatment of premature ejaculation. J Sex Marital Ther 1996; 22:85-96.

[32.] Saenz de Tejada I, Ware JC, Blanco R, Pittard JT, Nadig PW, Azadzoi KM, et al. Pathophysiology of prolonged penile erection associated with trazodone use. J Urol 1991; 145:60-4.

[33.] Murjack DJ, Crocker B. Alprazolam-induced ejaculatory inhibition. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1986; 6:57-8.

[34.] Uhde TW, Tancer ME, Shea CA. Sexual dysfunction related to alprazolam treatment of social phobia. Am J Psychiatry 1988; 145:531.

[35.] Coates NE. Priapism associated with Buspar. South Med J 1990; 83:983.

[36.] Ghadirian AM, Annable L, Belanger MC. Lithium benzodiazepines and sexual function in bipolar patients. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:801-5.

[37.] Kowalski A, Stanley RO, Dennerstein L, Burrows G, Maguire KP The sexual side-effects of antidepressant medication: a double-blind comparison of two antidepressants in a non-psychiatric population. Br J Psychiatry 1985;147:413-8.

[38.] Mattson RH. Comparison of carbamazepine phenobarbital phenytoin and primidone in partial and secondarily generalized tonic-clonic seizures. N Engl J Med 1985; 313:145.

[39.] Jensen RT, Collen MJ, Pandol SJ, Allende HD, Raufman JP, Bissonnette BM, et al. Cimetidine-induced impotence and breast changes rn patients with gastric hypersecretory states. N Engl J Med 1983; 308:883.

[40.] Oliver MF, Heady JA, Morris JN, Cooper J. A cooperative trial in the primary prevention of ischaemic heart disease using clofibrate. Report from the Committee of Principal Investigators. Br Heart J 1978; 40:1069-118.

[41.] Hosea SW, Santaella ML, Brown EJ, Berger M, Katasha K, Frank MM. Long-term therapy of hereditary angioedema with danazol. Ann Intern Med 1980; 93:809.

[42.] Nen A, Zukerman S, Aygen M, Lidor Y, Kaufman H. The effect of longterm administration of digoxin on plasma androgens and sexual dysfunction. J Sex Marital Ther 1987; 13:58.

[43.] Snyder S, Karaca I, Salis PJ. Disulfiram and nocturnal penile tumescence in the chronic alcoholic. Biol Psychiatry 1981; 16:399.

[44.] Pont A, Graybill JR, Craven PC, Galgiani JN, Dismokes WE, Reitz RE, Stevens DA. High-dose ketoconazole therapy and adrenal and testicular function in humans. Arch Intern Med 1984; 144:2150-3.

[45.] The Coronary Drug Project Research Group. Clofibrate and niacin in coronary heart disease. JAMA 1975; 231:360-81.

[46.] Hrrschkowitz M, Karacan I, Howell JW, Arcasoy MO, Williams RL Nocturnal penile tumescence in cigarette smokers with erectile dysfunction. Urology 1992; 39:101-7.

[47.] Mannino DM, Klevens RM, Flanders WD. Cigarette smoking: an independent risk factor for impotence? Am J Epidemiol 1994; 140:1003-8.

[48.] Buffum J, Moser C. MDMA and human sexual function J Psychoactive Drugs 1986; 18:355-9.

[49.] Van Arsdalen K, Wein AJ. Drugs and male sexual dysfunction. American Urological Association Update Series 1984; 3(34): 1-7.

[50.] Wei N. Naproxen and ejaculatory dysfunction. Ann Intern Med 1980; 93:933.

[51.] Abramawicz M. Drugs that cause sexual dysfunction. Med Lett Drugs Ther 1987; 29:65-70.

Submitted, revised, December 4, 1996. This paper was presented at the XXVIII Annual Conference of the American Association of Sex Educators, Counselors and Therapists. April, 1995, Albuquerque, New Mexico. William W, Finger, PhD; Margaret Lund, PharmD; and Mark S. Slagle, PharmD, From the Mountain Home Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Johnson City, Tennessee (WWF, M.A.S.), and the Dayton VAMC and Grandview Hospital, Dayton, Ohio (M.L.). Requests for reprints should be addressed to William W Finger, PhD, Psychology Service 116B2, Johnson City VAMC, PO Box 4000, Mountain Home, TN 37684-4000. E-mail: finger. william@mtn-home.va.gov

COPYRIGHT 1997 Dowden Health Media, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group