Pregnancy unmasks fatal metabolism defect

When a 21-year-old woman complained of headache and confusion eight days after giving birth to a healthy baby, physicians mistakenly diagnosed her as suffering from postpartum depression and admitted her to a psychiatric unit. Three days later, the woman went into coma and a week later, she died.

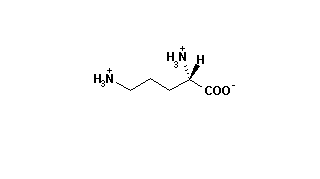

This dramatic case stumped physicians until the woman's blood revealed a telltale high level of ammonia, a diagnostic clue suggesting a rare, inherited disorder called ornithine carbamoyltransferase deficiency. The disease results from a defective gene located on the X chromosome that codes for the enzyme ornithine carbamoyltransferase, which the body needs to metabolize nitrogen-containing compounds derived from protein in the diet. Without enough functional enzyme, toxic ammonia builds up in the bloodstream and can lead to vomiting, seizures, coma and sometimes death.

Physicians know this enyme deficiency strikes male newborns who inherit the faulty gene from their mother. While a few female carriers develop the disease during childhood, most show no symptoms and up until now scientists believed asymptomatic adult carriers had escaped the disorder entirely.

Now Pamela Hawks Arn of the Nemours Children's Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla., Saul W. Brusilow of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore and colleagues report in the June 7 NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE that healthy female carriers may run a lifelong risk of potentially lethal episodes of high blood-ammonia levels. At the same time, another study in the same issue describes a new method of identifying such carriers.

In the first report, Arn, Brusilow and their co-workers describe five healthy women who abruptly developed toxic blood levels of ammonia and went into coma. All carried the mutant gene causing ornithine carbamoyltransferase deficiency, and two of the five subsequently died.

"What we found is that there are these women who are normal under ordinary circumstances, but when faced with some sort of [physical] stress they get sick," says Brusilow. Carriers have enough functional enzyme under most circumstances but may succumb to high blood ammonia levels when the body is under extreme duress, such as the postpartum period following childbirth, he notes.

Three of the five women got sick after delivering a healthy infant who did not inherit the flawed gene, according to the report. The team speculates that in such cases the healthy fetus may metabolize nitrogen compounds that pass through the placenta from the maternal bloodstream. "We hypothesize that the fetus was handling the ammonia and when the fetus was delivered the woman had a sudden loss of this biochemical factory," Brusilow says. The scientists cannot explain the trigger that led to coma for the two nonpregnant women in their study.

The team also found evidence that carriers abnormally metabolize protein all the time, even when these women show no symptoms of the disease. More research must identify periods when such abnormalities can progress to full-fledged disease, Brusilow says. Arthur L. Horwich of Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven, Conn., comments in an accompanying editorial that at least several thousand U.S. female carriers may run the risk of developing life-threatening episodes of high blood ammonia.

In a companion study in the same issue, Brusilow, Elizabeth R. Hauser and colleagues at Johns Hopkins report a new way to identify carriers of this rare genetic disorder. The method is safer than the current test, which can trigger attacks of high blood ammonia in some carriers, the researchers say.

COPYRIGHT 1990 Science Service, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group