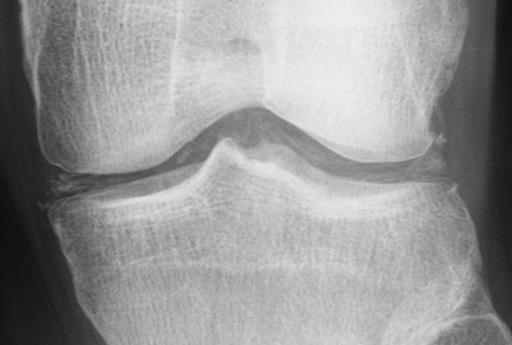

Joint pain is among the most common complaints encountered in family practice. (1) Many joint disorders initially can produce pain and swelling in a single joint. Because patients with acute monoarthritis often present to their family physician, a proper diagnostic approach is important (Figure 1).

[FIGURE 1 OMITTED]

Etiology of Acute Monoarthritis

Acute monoarthritis in adults can have many causes (Table 1), but crystals, trauma, and infection are the most common. Prompt diagnosis of joint infection, which often is acquired hematogenously, is crucial because of its destructive course. A prospective, three-year study (2) found that the most important risk factors for septic arthritis are a prosthetic hip or knee joint, skin infection, joint surgery, rheumatoid arthritis, age greater than 80 years, and diabetes mellitus. Intravenous drug use and large-vein catheterization are predisposing factors for sepsis in unusual joints (e.g., sternoclavicular joint). (3)

Gonococcal arthritis is the most common type of nontraumatic acute monoarthritis in young, sexually active persons in the United States. It is three to four times more common in women than in men. (4,5) Nongonococcal septic arthritis, the most destructive type, generally is monoarticular (80 percent of cases) and most often affects the knees (50 percent of cases). (3,6) Staphylococcus aureus is the most common pathogen in nongonococcal septic arthritis (60 percent in some series), but non-group-A beta-hemolytic streptococci, gram-negative bacteria, and Streptococcus pneumoniae can be present. (3)

Anaerobic and gram-negative infections are common in immunocompromised persons. Inflammation of a single large joint, especially the knee, may be present in Lyme disease. Mycobacterial, fungal, and viral infections are rare. Monoarticular inflammation can be the initial manifestation of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. (7)

Many types of crystals can trigger acute monoarthritis, but monosodium urate (which causes gout) and calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate (CPPD, which causes pseudogout) are the most common. Calcium oxalate (especially in patients who are receiving renal dialysis), apatite, and lipid crystals (8) also elicit acute monoarthritis.

Transient arthritis sometimes results from intra-articular injection of corticosteroids. Osteoarthritis may worsen suddenly and manifest as pain and effusion. Spontaneous osteonecrosis may occur in patients with risk factors such as alcoholism or chronic corticosteroid use. Aseptic loosening is often the source of pain in a prosthetic joint. Infection, commonly from a skin source, is also possible and requires urgent attention.

History

Any acute inflammatory process that develops in a single joint over the course of a few days is considered acute monoarthritis (also defined as monoarthritis that has been present for less than two weeks). (9) Establishing the chronology of symptoms is important (Table 2). Rapid onset over hours to days usually indicates an infection or a crystal-induced process. Fungal or mycobacterial infections usually have an indolent and protracted course but can mimic bacterial arthritis.

Fractures and ligamentous or meniscal tears resulting from trauma can present as mild to moderate monoarticular swelling. (10) The pain characteristically worsens with movement and improves with rest. There may be no history of trauma in patients with fractures secondary to osteoporosis. (11) Penetrating injuries, such as those from thorns, can cause acute synovitis, with symptoms sometimes occurring months after the injury. (12)

Patients might note concurrent or preexistent involvement of other joints. Sequential monoarthritis in several joints is characteristic of gonococcal arthritis (5) or rheumatic fever. Monoarthritis occasionally is the first presenting symptom of an inflammatory polyarthritis such as psoriatic arthritis but is an unusual initial symptom of rheumatoid arthritis. When the history reveals longstanding symptoms in a joint, exacerbations of preexisting disease (e.g., worsening of osteoarthritis with excessive use) should be differentiated from a superimposed infection. In patients with rheumatoid arthritis, pain in one joint out of proportion to pain in other joints always suggests infection. (13)

Sexual history and history of illegal drug use, alcohol use, travel, and tick bites should be ascertained. Reactive arthritis sometimes can develop after a gastrointestinal or sexually transmitted disease. Certain occupations, such as farming and mining, frequently are associated with overuse injures and osteoarthritis.

Pseudogout affecting the wrists and knees is most common among elderly persons. Disseminated gonococcal infection, reactive arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis affect young adults. Gout, which occurs more often in men, affects the first metatarsophalangeal joint, ankle, mid-foot, or knee; accompanying fever, redness, and pain can mimic infection. Minor trauma can precipitate gout or introduce infection through a break in the skin. (8)

Physical Examination

When a patient complains of joint pain, the first step is to determine whether the source of the pain is the joint or a periarticular soft tissue structure such as a bursa or tendon. It is not uncommon to find that "hip pain" actually is the result of trochanteric bursitis. Asking the patient to point to the exact site may be helpful. (14) Unlike with true joint inflammation, redness or swelling generally is not present with periarticular pain. However, a patient with inflammation of certain bursae (e.g., prepatellar bursitis, olecranon bursitis) may present with redness or swelling that mimics joint inflammation.

True intra-articular problems cause restriction of active and passive range of motion, whereas periarticular problems restrict active range of motion more than passive range of motion. Maximum pain at the limit of joint motion (i.e., stress pain) is characteristic of true arthritis. In tendonitis or bursitis, joint movements against resistance elicit pain. For example, elbow pain resulting from septic arthritis occurs with active and passive motion in any direction. In contrast, elbow pain resulting from lateral epicondylitis (i.e., "tennis elbow") worsens with resisted active extension or supination of the wrist. Specific maneuvers can be diagnostic for other conditions, such as medial epicondylitis; bicipital and rotator cuff tendonitis; trochanteric bursitis; and patellar, prepatellar, and anserine bursitis. (15)

Joint effusion may not be readily visible. In the knee joint, the "bulge sign" can signal a small effusion. The medial or lateral compartment is stroked, and the fluid moves through the suprapatellar area into the opposite compartment, resulting in a visible bulge. To detect effusion in the elbow joint, the triangular recess (area between lateral epicondyle, olecranon process, and radial head) in the lateral aspect should be palpated. To detect effusion in the ankle, the joint should be palpated anteriorly. Maneuvers for examining other joints are reviewed elsewhere. (16)

Joint pain may be referred from internal organs (e.g., shoulder pain in a patient with angina). Referred pain should be suspected in patients with a normal joint examination.

The general physical examination may provide other diagnostic clues (Table 2) or reveal involvement of other joints. Fever and tachycardia may signal infection, but they are not reliable indicators, especially in immunocompromised patients and patients who are taking corticosteroids or antibiotics. Patients with gonococcal infection may have a rash, pustules, or hemorrhagic bullae. Patients with longstanding gout may have tophi (i.e., firm subcutaneous deposits of urate) over the olecranon prominence, first metatarsal joints, or pinnae. Patients with reactive arthritis may have inflamed eyes. A new cardiac murmur and splinter hemorrhages in the nail folds suggest endocarditis.

Diagnostic Studies

Arthrocentesis is required in most patients with monoarthritis and is mandatory if infection is suspected. In some instances, obtaining as little as one or two drops of synovial fluid can be useful for culture and crystal analysis.

For arthrocentesis, the joint line is identified, and a pressure mark is made on the overlying skin with the closed end of a retractable pen. The skin is cleansed, and a needle is inserted without the physician's finger touching the marked site, unless a sterile glove is worn. If the fluid withdrawn is initially bloody rather than becoming bloody during aspiration, previous hemarthrosis should be suspected. Additional details on performing arthrocentesis are available elsewhere. (17,18)

Superimposed cellulitis is a relative contraindication to arthrocentesis. The procedure can be performed safely in patients who are taking warfarin (Coumadin). (19) An experienced physician should perform arthrocentesis in these patients and use the smallest possible needle size.

Removal of as much synovial fluid as possible offers symptomatic relief and helps to control infection. If the fluid is loculated, aspiration of large amounts of fluid will be difficult; massaging the joint may help increase the amount of fluid aspirated. If infection is suspected, intravenous antibiotics should be administered before culture results become available. If needle drainage is ineffective, urgent arthroscopic or surgical drainage is indicated. Until infection has been ruled out, corticosteroids should not be injected into a joint.

If even the smallest suspicion of infection exists, synovial fluid should be sent for a white blood cell (WBC) count with differential (specifically, the percentage of polymorphonuclear neutrophilic leukocytes), crystal analysis, Gram staining, and culture. Lipid panels and synovial fluid tests for other chemistries, proteins, (20) rheumatoid factor, or uric acid are not useful because the results may be misleading.

Sterile tubes should be used for culture. If examinations are delayed, a tube with ethylenediaminetettraacetic acid should be used for anticoagulation, because anticoagulants (e.g., oxalate, lithium heparin) used in other tubes can confound crystal analysis. (18) Synovial fluid cultures are more likely to be positive in patients with nongonococcal arthritis (90 percent) than in those with gonococcal arthritis (less than 50 percent). (21)

Synovial fluid may be categorized as noninflammatory, inflammatory, or hemorrhagic, depending on the appearance and cell counts (Table 3). Normal synovial fluid is colorless and transparent. Noninflammatory synovial fluid may be colorless or yellow and transparent enough to read through, whereas inflammatory synovial fluid is not transparent.

If a polarized microscope is not available, a tentative diagnosis can be made if needle-shaped monosodium urate crystals are identified using an ordinary light microscope (22) (Figure 2). CPPD crystals are smaller rods, squares, or rhomboids and are difficult to identify with light microscopy. The finding of crystals within leukocytes is virtually diagnostic of crystal-induced arthropathy but does not rule out a superimposed infection (Table 4).

The complete blood cell count may show leukocytosis in some patients with infection. An erythrocyte sedimentation rate may distinguish inflammatory arthritis from noninflammatory arthritis, but this test is nonspecific and may be overused. Tests for HIV and Lyme disease antibodies may be obtained if appropriate, but serologies usually are not helpful in identifying the cause of acute monoarthritis. (9,23) Indiscriminately ordering tests such as rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibodies can result in confusion, because false-positive results are common.

Blood cultures should be obtained in patients with suspected septic arthritis. Cultures are positive in about 50 percent of nongonococcal infections (24) but are rarely positive (about 10 percent) in gonococcal infection. (25) Pharyngeal, urethral, cervical, and rectal swabs are necessary if gonococcal infection is suspected.

Although plain-film radiographs often show only soft tissue swelling, they are indicated in patients with a history of trauma or patients who have had symptoms for several weeks. Occasionally, unsuspected bony lesions, such as osteomyelitis or malignancy, may be detected. The presence of chondrocalcinosis could support but not confirm CPPD arthritis.

Radionuclide scanning can detect infection in deep-seated joints. Magnetic resonance imaging is superior in detecting ischemic necrosis, occult fractures, and meniscal and ligamentous injuries. Other diagnostic procedures, such as synovial biopsy or arthroscopy, may be useful to rule out deposition diseases (e.g., hemochromatosis, atypical infections) and intra-articular tumors.

Final Comment

Common pitfalls in the diagnostic approach to acute monoarthritis (Table 4) must be avoided, and the rough guidelines on synovial fluid classification (Figure 1 and Table 3) should not be interpreted too rigidly. Referral is indicated when the initial evaluation does not determine the cause of acute monoarthritis or when therapeutic intervention by specialists is required (Table 5). If infection is suspected, urgent consultation and culture should be obtained, and intravenous antibiotics should be administered to prevent rapid joint destruction.

The authors indicate that they do not have any conflicts of interest. Sources of funding: Drs. Siva and Velazquez received funding from the Arthritis Foundation, Eastern Missouri Chapter. Dr. Mody's work was funded by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

REFERENCES

(1.) Stange KC, Zyzanski SJ, Jaen CR, Callahan EJ, Kelly RB, Gillanders WR, et al. Illuminating the 'black box'. A description of 4454 patient visits to 138 family physicians. J Fam Pract 1998;46:377-89.

(2.) Kaandorp CJ, Van Schaardenburg D, Krijnen P, Habbema JD, van de Laar MA. Risk factors for septic arthritis in patients with joint disease. A prospective study. Arthritis Rheum 1995;38:1819-25.

(3.) Goldenberg DL. Septic arthritis. Lancet 1998;351: 197-202.

(4.) O'Brien JP, Goldenberg DL, Rice PA. Disseminated gonococcal infection: a prospective analysis of 49 patients and a review of pathophysiology and immune mechanisms. Medicine [Baltimore] 1983; 62:395-406.

(5.) Cucurull E, Espinoza LR. Gonococcal arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 1998;24:305-22.

(6.) Mikhail IS, Alarcon GS. Nongonococcal bacterial arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 1993;19:311-31.

(7.) Berman A, Cahn P, Perez H, Spindler A, Lucero E, Paz S, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus infection associated arthritis: clinical characteristics. J Rheumatol 1999;26:1158-62.

(8.) Reginato AJ, Schumacher HR, Allan DA, Rabinowitz JL. Acute monoarthritis associated with lipid liquid crystals. Ann Rheum Dis 1985;44:537-43.

(9.) Freed JF, Nies KM, Boyer RS, Louie JS. Acute monoarticular arthritis. A diagnostic approach. JAMA 1980;243:2314-6.

(10.) Till SH, Snaith ML. Assessment, investigation, and management of acute monoarthritis. J Accid Emerg Med 1999;16:355-61.

(11.) Cibere J. Rheumatology: 4. Acute monoarthritis. CMAJ 2000;162:1577-83.

(12.) Baker DG, Schumacher HR Jr. Acute monoarthritis. N Engl J Med 1993;329:1013-20.

(13.) Goldenberg DL. Infectious arthritis complicating rheumatoid arthritis and other chronic rheumatic disorders. Arthritis Rheum 1989;32:496-502.

(14.) Ensworth S. Rheumatology: 1. Is it arthritis? CMAJ 2000;162:1011-6.

(15.) Sheon RP, Moskowitz RW, Goldberg VM. Soft tissue rheumatic pain: recognition, management and prevention. 3d ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1996:79-146,209-74.

(16.) El-Gabalawy H. Evaluation of the patient: history and physical examination. In: Klippel JH, Weyand CM, Crofford LJ, Stone JH. Primer on the rheumatic diseases. 12th ed. Atlanta: Arthritis Foundation, 2001:117-24.

(17.) Schaffer TC. Joint and soft-tissue arthrocentesis. Prim Care 1993;20:757-70.

(18.) Fye KH. Arthrocentesis, synovial fluid analysis, and synovial biopsy. In: Klippel JH, Weyand CM, Crofford LJ, Stone JH. Primer on the rheumatic diseases. 12th ed. Atlanta: Arthritis Foundation, 2001:138-9.

(19.) Thumboo J, O'Duffy JD. A prospective study of the safety of joint and soft tissue aspirations and injections in patients taking warfarin sodium. Arthritis Rheum 1998;41:736-9.

(20.) Shmerling RH, Delbanco TL, Tosteson AN, Trentham DE. Synovial fluid tests. What should be ordered? JAMA 1990;264:1009-14.

(21.) Wise CM, Morris CR, Wasilauskas BL, Salzer WL. Gonococcal arthritis in an era of increasing penicillin resistance. Presentations and outcomes in 41 recent cases (1985-1991). Arch Intern Med 1994; 154:2690-5.

(22.) Pascual E, Tovar J, Ruiz MT. The ordinary light microscope: an appropriate tool for provisional detection and identification of crystals in synovial fluid. Ann Rheum Dis 1989;48:983-5.

(23.) McCune WJ, Golbus J. Monoarticular arthritis. In: Ruddy S, Harris ED, Sledge CB, Kelley WN. Kelley's Textbook of rheumatology. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2001:367-77.

(24.) Esterhai JL Jr, Gelb I. Adult septic arthritis. Orthop Clin North Am 1991;22:503-14.

(25.) Cucurull E, Espinoza LR. Gonococcal arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 1998;24:305-22.

CHOKKALINGAM SIVA, M.D., is a research fellow in the Division of Rheumatology at Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis. After graduating from the University of Madras, India, he completed an internal medicine residency at Marshfield (Wis.) Clinic.

CELSO VELAZQUEZ, M.D., is a clinical fellow in the Division of Rheumatology at Washington University School of Medicine. Dr. Velazquez graduated from the National University of Asuncion, Paraguay, and completed an internal medicine residency at Rush-Presbyterian-St. Luke's Medical Center, Chicago.

AMI MODY, M.D., is a clinical fellow in the Division of Rheumatology at Washington University School of Medicine. A graduate of the University of Bombay, India, Dr. Mody completed an internal medicine residency at St. Vincent's Hospital, Cleveland.

RICHARD BRASINGTON, M.D., is associate professor and director of clinical rheumatology at Washington University School of Medicine, where he also directs the Center for Clinical Studies and the fellowship program in rheumatology. Dr. Brasington graduated from Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, N.C., and completed a residency and fellowship at the University of Iowa College of Medicine, Iowa City.

Address correspondence to Richard Brasington, M.D., Washington University School of Medicine, Box 8045, 660 S. Euclid Ave., St. Louis, MO 63110 (e-mail: rbrasing@im.wustl.edu). Reprints are not available from the authors.

CHOKKALINGAM SIVA, M.D., CELSO VELAZQUEZ, M.D., AMI MODY, M.D., and RICHARD BRASINGTON, M.D. Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri

COPYRIGHT 2003 American Academy of Family Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2003 Gale Group