Renal colic is a common condition among deployed soldiers in the Middle East. Eight percent of all admissions to the jump package of the 21st Combat Support Hospital in Mosul, Iraq, during Operation Iraqi Freedom involved patients with renal colic and urinary stones. The majority of patients were treated successfully with primary care measures. Fourteen percent of patients required urologie interventions; however, many of these soldiers were treated with ureteral stents and returned to duty. Aggressive management of urolithiasis resulted in 92% of soldiers remaining in the combat zone, preserving the fighting strength of supported units.

Introduction

The 21st Combat Support Hospital (CSH) was the first to undergo the Medical Re-Engineering Initiative and deploy into a combat zone. Immediately upon entering Iraq, the 21st CSH went into split operations, with the smaller 44-bed jump package element moving to Northern Iraq, 200 miles north of the main body of the hospital. The jump team included one urologist, one family practitioner, and one internist. Soldiers deployed to warm climates such as the Middle East have a high incidence of urinary stone formation among otherwise healthy individuals with no previous history of urolithiasis. This is likely attributable to significant fluid loss from perspiration and limited water supply, resulting in concentrated urine that predisposes the soldiers to stone formation.

Observations

The 21st CSH North (jump package) supported the 19,000 soldiers of the 101st Airborne Division. The hospital treated 7,614 outpatients and 1,105 inpatients in the 5-month period (157 days) beginning in late April 2003. Eighty-four soldiers (8% of all admissions) were admitted for renal colic. This review does not include soldiers with urinary lithiasis who were treated as outpatients by the CSH or level II facilities; the overall incidence of stone disease cannot be determined. All patients were diagnosed and monitored to resolution with a combination of abdominal plain-film radiography, renal ultrasonography, and intravenous pyelography. The overwhelming majority of renal colic patients presented with single, small, distal ureteral calculi. Most were successfully treated with analgesics, antiemetics, and intravenous fluids.

Twelve patients (14%) had complicated stone disease, defined by the volume of stone burden (multiple calculi and stones > 10 mm in diameter; i.e., those with minimal chance of spontaneous resolution with or without a ureteral stent), prolonged intractable pain, protracted nausea and vomiting, or fever. We considered the requirement for >72 hours of parenterally administered narcotics as the definition of intractable pain. Patients with complicated stone disease underwent urologic intervention and/or evacuation from the combat zone.

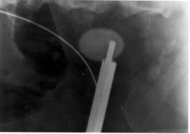

The CSH urologie equipment is limited to a cystoscope. No ureteroscope or instruments for lithotripsy are available. The only intervention available in the deployed CSH is placement of an internal ureteral stent. Indwelling ureteral stents have been successfully used as definitive therapy for ureteral calculi.1 The stent bypasses the obstructing calculus and allows urine to flow through or around the stent, beyond the stone, from kidney to bladder. Ureteral stents can be placed with or without formal anesthesia. The lack of fluoroscopy prolongs the procedure while hard-copy radiographs are processed to document guidewire and stent location. For this reason, all patients requiring stents received general or regional anesthesia for the approximately 20-minute procedure.

In addition to the benefits of bypassing the obstructing calculus, the stent is soft and pliable and does not interfere with normal duty or activity, passively dilates the ureter, and eliminates ureteral peristalsis. The immediate result is the soldiers becoming free of pain and returning to their units with the stent internalized. A small string is left attached to the distal end of the stent, just visible at the urinary meatus. Patients returned to the CSH in 11 to 14 days for stent removal, which was accomplished grasping the string and applying gentle traction.

Results

Seventy-two patients (86%) were successfully treated medically and returned to duty. Of the 12 patients with complicated stones, 7 had significant stone burden (multiple stones and calculi > 10 mm in diameter) and a history of previous calculary disease. These soldiers were evacuated to the level IV facility for definitive care. Five patients (four male and one female) with a single ureteral calculus

Discussion

Causes and risk factors for urinary stone disease are multifactorial. Common predisposing factors include diet (low fluid intake, high sodium intake, or high protein consumption), metabolic abnormalities (hypercalciuria, hyperuricosuria, hyperoxaluria, hypocitraturia, hypomagnesuria, orcystinuria), and urinary tract obstruction and infection. Stone disease affects 10% of the population in North America and Europe, with urolithiasis occurring more frequently in hot arid areas than in temperate regions.2 Countries in the Middle East have a higher incidence of stone disease, with urolithiasis accounting for >40% of the urologie inpatient workload.3 Soldiers' risks in the Middle East environment are likely increased because of reduced water intake and increased perspiration, resulting in concentrated urine, as well as increased sodium and protein contents in combat rations. During World War II, the rate of urinary stone disease was three times higher among United States service members in the Middle East, compared with soldiers serving in the European theater, and the incidence of stone disease increased in hot summer months and decreased in cooler winter months.4

Medical providers should expect and prepare for a high incidence of renal colic among troops deployed to warm environments. Primary care providers can treat most patients with urolithiasis, because standard medical therapy alone for acute symptoms resulted in successful spontaneous stone resolution for the majority of patients. Acute medical management includes hydration, analgesics, and antiemetics. Virtually all patients presented with very concentrated urine (specific gravity of > 1.025). Fluids (normal saline and lactated Ringer's solutions) administered to compensate for baseline deficits and to promote diuresis were monitored with urine output and specific gravity measurements. The goals of fluid therapy were a specific gravity of 1.010 or better and a daily urine output of >2 L. Enterally and parenterally administered narcotics and the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agent ketorolac were used liberally to reduce pain. Parenterally administered antiemetics were used as needed; many patients with symptomatic stone disease experience nausea and vomiting. Adequate symptom control allowed patients to take orally administered fluids and to walk. Patients were monitored with urinalysis and kidney-ureter-bladder radiography or ultrasonography to assess the progression of stones, and urine was strained to collect passed calculi.

Some soldiers with complicated stones can be treated at the CSH and kept in the combat zone with the use of ureteral stents for selected patients. Fourteen percent of patients admitted for stone disease required intervention or evacuation. Soldiers with protracted pain and solitary stones of

Medical providers should attempt to preserve the fighting strength of supported units and to treat as many patients as far forward as possible. Management of urinary stone disease as described here limited evacuation to 8% of soldiers admitted to the CSH with renal colic. Ninety-two percent of patients requiring admission for renal colic were successfully treated and returned to duty.

References

1. Levenlhal EK. Rozanski TA. Crain TW. Deshon GE: Indwelling ureteral stents as definitive therapy for distal ureteral calculi. J Urol 1995: 153: 34-6.

2. Tiselius HG: Epidemiology and medical management of stone disease. BJU Int 2003; 91: 758-67.

3. Rizvi SAH, Naqvi SAA, Hussain Z. et al: The management of stone disease. BJU Int 2002: 89(Suppl 1): 62-8.

4. Reiser C: Urologie aspects of systemic disease. In: Surgery in World War II, pp 204-6. Edited by Patton JF. Washington, DC. Office of the Surgeon General and Center of Military History. United States Army. 1987.

Guarantor: COL Thomas A. Rozanski, MC USA

Contributors: COL Thomas A. Rozanski, MC USA*; COL Jeffrey M. Edmondson, MC USA[dagger]

* Department of Surgery, 21st Combat Support Hospital (North), APO AE 09325, Mosul, Iraq.

[dagger] Department of Medicine. 21st Combat Support Hospital (North), APO AE 09325. Mosul, Iraq.

Opinions and assertions contained in this article are the private views of the authors and should not be construed as reflecting the views of the United States Army or the Department of Defense.

This manuscript was received for review in October 2003. The revised manuscript was accepted for publication in July 2004.

Copyright Association of Military Surgeons of the United States Jun 2005

Provided by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights Reserved