An outbreak of measles that occurred in Anchorage, Alaska, in 1998 resulted in 33 diagnosed cases: 26 were laboratory confirmed and 7 were clinically confirmed. Twenty-nine (88%) of 33 cases occurred in individuals who had not been immunized with at least two measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccinations; 25 (76%) of 33 occurred in school-age children, 0 to 19 years of age. This study identifies the difference in the incidence of measles between the civilian school-age population, who was not completely immunized (two MMR vaccinations given at least 30 days apart), and the military dependent population who had been completely immunized. All cases occurred among civilians, and most (25 of 33 confirmed cases) were associated with school attendance. The authors conclude that a two-dose regimen of MMR vaccine is required to adequately protect individuals against measles.

Introduction

Anchorage, Alaska, experienced the largest measles outbreak in the United States from September through November 1998. From January 1 through September 18, 1998, only 50 cases of measles had been reported to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for the entire United States.1 Reported cases from the Anchorage outbreak totaled 33, which included 26 laboratory confirmed and 7 clinically confirmed cases. Nine other reported cases were considered probable, but were not confirmed. The disease was introduced into the Anchorage metropolitan area in mid-August by a 4-year-old Japanese tourist. This case was confirmed by laboratory testing.2 During the period from September through November 1998, the illness spread; 29 (88%) of 33 confirmed cases occurred in persons who had received only one measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccination before exposure, one case occurred in an individual with two MMR vaccinations before exposure, and three cases had unknown vaccination histories. Twenty-five (76%) of 33 cases were observed in school-age children and were associated with exposure at school.

This report looks at the distribution of measles in the Anchorage, Alaska, outbreak and the incidence rates observed in those with and without access to military health care. No cases of measles were diagnosed in the military population, which was defined as active duty, retirees, and dependents of active duty and retirees. We conclude that the prevention of measles was associated with complete immunization (at least two injections administered at least 30 days apart) before exposure. To accurately compare similar populations, this study is limited to the school-age and younger civilian and military dependent populations.

Background

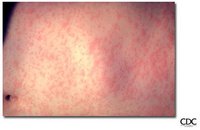

Measles is a highly contagious viral disease caused by rubeola virus (a member of the genus Morbiilwirus of the family Paramyxovindae). The disease is characterized by fever, cough, conjunctival injection, coryza, an erythematous maculopapular rash, and a pathopneumonic lesion on the buccal mucosa (koplik spot). Complications include pneumonia, laryngotracheobronchitis, diarrhea, and acute encephalitis with resultant neurological sequelae. Fatality occurs in 1 to 2 of 1,000 cases as a result of pulmonary or neurological complication. Young children, nonimmunized individuals, and individuals who have a compromised immune system are at highest risk.3

This vaccine-preventable disease has been controlled in the United States since 1968 by widespread childhood immunizations, which are usually administered as a MMR vaccine. Protective immunity can be attained in children by administering two injections of the vaccine, with the first dose recommended at 12 to 15 months of age and the second dose at 4 to 6 years of age. Immunity in older persons is attained by two shots at least 30 days apart. This vaccination schedule is known to prevent illness from measles and has also proven effective in stopping outbreaks of measles if administered to a susceptible population.

Populations Defined

The susceptible population in the Anchorage, Alaska, outbreak was defined as persons who had not received a complete immunization (i.e., had not received at least two vaccinations) before the outbreak. Before 1996, Alaska did not require a second MMR for entry into primary school; many school-age children in Anchorage had not completed a two-shot series. Persons who lacked documentation of complete immunization were predominately individuals who received their health care from nonmilitary delivery systems. Civil service employees do not have access to the military health care delivery system unless they are military retirees. Most individuals who had access to the military health care delivery system had documentation of complete immunization in their records. Complete immunization or infection of susceptible persons occurred within 3 months, the duration of the outbreak.

The most susceptible population in Anchorage and the surrounding area was school-age and younger persons. The population of Anchorage in the 0- to 19-year age group is reported to be 84,025, according to the 19XX census data.4 The military community in the Anchorage area consists of members of the Air Force, Army, Marines, Navy, and Coast Guard. The number of military dependents of active duty and retired personnel between the ages of O and 19 years is reported to be 10,658 (Table I).

Control Method

Publicity

The measles outbreak was widely publicized throughout southern Alaska with a press conference held on September 25, 1998. Representatives from local newspapers, television, and radio stations were present at the conference, and the local media gave extensive coverage to the outbreak. In addition, many signs and placards with information about the outbreak and how to prevent the spread of disease were posted in public buildings around the city. Civilian providers were instructed to report suspected cases of measles directly to the State of Alaska Department of Health and Social Services, Division of Public Health, section of Epidemiology. Military providers were instructed to report cases to the military Public Health Office, which forwarded the reports to the State of Alaska Department of Health and Social Services. A case definition for suspected measles was established: any febrile illness accompanied by a rash. Probable measles was considered if the patient presented with a generalized rash, a temperature of > or = 101°F, and a cough, runny nose, or conjunctivitis. Providers seeing cases of suspected measles attempted to confirm the diagnosis.

Laboratory Diagnosis

Laboratory-confirmed measles was determined by demonstrating positive serologie evidence for measles immunoglobulin M antibody from a serum sample drawn on or after day 4 of the rash, a viral culture, or both. Clinically confirmed measles was defined as a case that met the definition of probable and was epidemiologically linked to a laboratory-confirmed case. In the Anchorage, Alaska, outbreak, 26 cases were laboratory confirmed and 7 were clinically confirmed.

Surveillance

Military and civilian providers provided medical surveillance for illness. Civilians who experienced suspected measles received medical care from private medical providers or neighborhood health clinics operated by the State of Alaska Department of Health and Social Services. Although most military members obtain medical care through military providers, there are active duty families in the Anchorage area who live long distances from the military hospital, and some members of those families obtained (or may have obtained) care from civilian providers. The Anchorage area is also home to many retired military persons, some with dependent children, and many of them chose medical care outside military channels. Surveillance for measles was considered to be very good because medical care was generally available to anyone with a need.

Immunization and Treatment

Because treatment for uncomplicated measles is supportive, the main focus of medical care was to control the outbreak and ensure complete immunization of the susceptible population. As a result of a previous measles outbreak that had occurred in juneau, Alaska, in 1996, the state had amended school regulations to require that children entering kindergarten and first grade receive two doses of measles vaccine before school entry.5 Because of the Anchorage outbreak of 1998, this regulation was expanded to include students in kindergarten through 12th grades. Immunization was also highly recommended for any person born after 1957 who did not have documentation of two doses of measles vaccine given at least 30 days apart. Routine measles vaccination time for babies was temporarily lowered to include 6- to 12-month olds. A massive immunization campaign, staff for which included civilian authorities, military providers, and qualified volunteers, was launched. Vaccination clinics were held at various locations, including many of the high schools in Anchorage, the military hospital at Elmendorf Air Force Base, and the clinic at Fort Richardson Army Post. A total of 29,036 immunizations was administered during the period from September 22 through November 17, 1998, with 2,286 given by military providers and 26,750 by civilian providers. Although the exact number is not available, the State of Alaska Department of Health and Social Services, Division of Public Health, section of Epidemiology reported that almost all of the doses given in the civilian sector were administered to preschool and school-age persons. The military immunization clinics determined that they gave only 27% to preschool and school-age persons.

Data Analysis

Twenty-five (76%) of 33 measles cases were observed in the age group of O to 19 years. A comparison of civilian and military dependent school and preschool age children was made, and the prevalence of measles cases by age group was determined (Table II).

Cases

From mid-August to November 17, 1998, 33 confirmed cases of measles were reported from the civilian population. Of these reported cases, 25 cases were reported in persons ages O to 19 years. The incidence rate among school-age civilian persons was calculated as 25 ÷ 73,367 or 0.341 cases per 1,000.

Military dependents reside throughout the city of Anchorage and are enrolled in every school in Anchorage and the surrounding area. Activities and socialization behavior are indistinguishable between military dependents and nonmilitary persons of similar age. Using the measles incidence rate of 0.341 per 1,000 calculated for the civilian school-age population, it is logical to have expected a similar incidence among military dependents or at least three cases.

During the outbreak period, there were no reported cases from the military dependent population. First, the likelihood of the two observed incidence rates arising from the a single population if the overall incidence rate was 0.341 cases per 1,000 school-age individuals was tested and was significant at p

If the 10,000 military-associated school and preschool age children are truly a subset of the Anchorage population and at risk of an infection at a rate of 3 per 10,000, the likelihood of observing no cases of measles in the military-associated dependent population is less than 10% (90% conifidence interval).

Discussion

Measles remains a significant infectious disease, with 36.5 million cases worldwide each year. More than 1 million deaths because of measles are reported annually, accounting for 10% of deaths in children under 5 years old. The incidence in the United States continues to drop, with 488 cases reported in 1996 and only 135 cases in 1997. In 1996,98% of children entering school had at least one measles vaccination, whereas 68% had two.6

In 1996, Alaska required one MMR for entry into school. In February 1996, there was a measles epidemic in juneau, concluding with 63 confirmed cases. At the time of the outbreak, 99% of juneau school children had received at least one measles vaccination. Before the juneau epidemic, there had not been a reported case of measles in the Alaskan school system since 1976.7 After the 1998 outbreak, a two-dose MMR schedule was implemented for students entering kindergarten through first grade.

During the 1998 Anchorage outbreak, there were two stratified populations. The civilian sector, grades 4 through 12, had been required to receive only one measles vaccine for school entry, whereas the Department of Defense children were uniformly given two MMRs, in compliance with the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommendations. Despite similar exposure risks, there were no confirmed cases of measles among the 10,658 Department of Defense dependent children, although there were 25 confirmed cases among the 73,367 nonmilitary children (0.341 per 1,000). Measures implemented to control the outbreak were well thought out and skillfully executed. Medical institutions and schools rallied behind the State of Alaska Department of Health and Social Services, Division of Public Health, initiative.

Two-dose MMR regimens have clearly demonstrated improved benefits over a single dose. China implemented the two-dose MMR schedule in 1985. This resulted in a reduction from 1 million measles cases with 4,200 deaths in 1981 to 75,000 with 108 deaths in 1996.6 A report of a 9-year follow-up study in Finland states that measles, along with mumps and rubella, infections have almost been eliminated in Finland.8 Measles incidence has also been shown to decrease after implementation of two-dose regimens in studies in the United States and Cuba,9 Israel,I0 Ireland,11 and Saudi Arabia,12 and studies have found increased levels of measles antibody in children who have had two doses of vaccine.11'13

Conclusion

As a result of this epidemic, the entire state has moved toward requiring two MMR immunizations for all school-age children. The present work supports the conclusion that two-dose vaccinations for measles should be the standard regimen in Alaska.

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Notifiable diseases/deaths in selected cities weekly information. Morbid Mortal WkIy Rep 1998; 47: 765-70.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Transmission of measles among a highly vaccinated school population: Anchorage. AK. Morbid Mortal WkIy Rep 1999; 47: 1109-11.

3. Beneson AS: Control of Communicable Diseases Manual, Ed IG. Washington, DC, Official Report of the American Public Health Association.

4. Alaska Department of Labor, Research and Analysis section, Demographics Unit.

5. Stale of Alaska Department of Health and Social Services: Epidemiology Bulletin No. 18. Division of Public Health, section of Epidemiology, April 30, 1996.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Advances in global measles control and elimination: summary of the 1997 international meeting. Morbid Mortal WkIy Rep 1998; 47: 000-000.

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Measles outbreak among school aged children: juneau, Alaska. Morbid Mortal WkIy Rep 1996; 45: 000-000.

8. Davidkin I, Valle M, julkunen I: Persistence of anti-mumps virus antibodies after a two-dose MMR vaccination. A nine-year follow-up. Vaccine 1995; 13: 1617-22.

9. De Quadras CA, Olive JM, Hersh BS, et al: Measles elimination in the Amcricas: evolving strategies. J Am Med Assoc 1996; 275: 224-9.

10. Slater PE, Anis E, LeventhalA: Measles control in Israel: a decade of the two-dose policy. Public Health Rev 1999; 27: 235-41.

11. Johnson H, Hillary IB, McQuiod G, Gilmer BA: MMR vaccination, measles epidemiology and scro-survcillance in the Republic of Ireland. Vaccine 1995; 13: 533-7.

12. Al-Mazrou YY, Al-Jeffri M, Ahmed OMM, Aziz KMS, Mishkas AH: Measles immunization: early two-doses policy experience. J Trop Pediatr 1999; 45: 98-104.

13. Watson JC, Pearson JA, Markowitz LE, et al: An evaluation of measles revaccination among school-entry-aged children. Pediatrics 1996; 97: 613-8.

Guarantor: Lt Col Michel Bunning, BSC USAF

Contributors: Lt Col Danny J. Glover, BSC USAF*; Jeffrey DeMain, MD FACAAIf; John R. Herbold, DVM MPH PhD[double dagger]; Paula J. Schneider, MS§; Lt CoI Michel Bunning, BSC USAFS¶

* 2105 Butterfly Maiden, NE, Albuquerque, NM 87112.

[dagger] 3300 Providence Drive, Suite 6, Anchorage, AK 99508.

[double dagger] School of Public Health, University of Texas Health Science Center, Mail Code 7676, 7703 Floyd Curl, San Antonio, TX 78229-3900.

§Clark C 242 A, Department of Journalism and Technical Communications, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523.

¶ Office of the Surgeon General, USAF, 1300 Rampart Road, Fort Collins, CO 80522.

This manuscript was received for review in December 2002. The revised manuscript was accepted for publication in june 2003.

Reprint & Copyright © by Association of Military Surgeons of U.S., 2004.

Copyright Association of Military Surgeons of the United States Jul 2004

Provided by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights Reserved