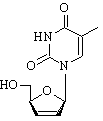

To the Editor: A 38-year-old, HIV-seropositive Nigerian man sought treatment with an 8-month history of severe parietal headache, impaired memory, fatigue, paresthesia of the left arm, and left-sided focal seizures. He had no history of neurologic disorders, including epilepsy. On physical examination, the patient appeared well, alert, and oriented, with slurred speech. Evaluation of the visual fields showed left homonymous hemianopsia. All other neurologic assessments were unremarkable. The patient had a blood pressure of 120/80, a pulse of 88 beats per minute, and a body temperature of 37.3[degrees]C. Leukocyte count was 8,600/[micro]L, total lymphocyte count was 1,981/[micro]L, CD4+ cell count was 102/[micro]L, and CD4/CD8 ratio was 0.07. HIV RNA-load was <50 copies/mL; all other laboratory parameters were normal. The patient had received antiretroviral therapy (stavudine, lamivudine, nevirapine) for 5 months before admission, but no prophylaxis for opportunistic infections. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain disclosed 2 masses, 3.3 and 4.8 cm in diameter, respectively (Figure A), and signs of chronic sinusitis. A computed tomographic chest scan showed infiltration of both lower segments with multiple, small nodules (Figure B). Blood cultures were repeatedly negative. A computer-guided needle-aspiration of the brain lesions yielded yellow-brown, creamy fluid in which abundant septated fungal hyphae were detected microscopically (Figure C). Cytologic investigation was consistent with a necrotic abscess. The cycloheximide-resistant isolate was strongly keratinolytic and identified as a Chwsosporium anamorph of Nannizziopsis vriesii (1,2). High-dose antimicrobial treatment with voriconazole (200 mg twice daily, subsequently reduced to 200 mg daily) was added to the antiretroviral (ritonavir, amprenavir, trizivir), anticonvulsive, and adjuvant corticosteroid treatment. The isolate was highly susceptible to voriconazole in vitro (MIC, [less than or equal to] 16[micro]/mL [Etest, AB-Biodisk Solna, Sweden]). Recovery was complicated by a generalized seizure and severe, acute psychosis associated with rapid refilling of the 2 lesions with mycotic abscess fluid. After re-aspiration, the patient's psychosis improved gradually, and no further seizures occurred. When last seen 4 months later, the patient was healthy and without neurologic deficits. His CD4+ cell count was 233/[micro]L, HIV-load was <50 copies/mL, and a MRI scan of the brain showed partial regression of the 2 brain lesions (Figure D).

[FIGURE OMITTED]

Chrysosporium spp. are common soil saprobes, occasionally isolated from human skin. Invasive infection is very rare in humans, and most were observed in immunocompromised patients, manifesting as osteomyelitis (3,4) or diffuse vascular brain invasion (5). Here, we report the first case of brain abscesses by the Chrysosporium anamorph of N. vriesii. This fungus has been associated with fatal mycosis in reptiles (6,7) and cutaneous mycosis in chameleons originating from Africa (2).

In our patient, we were unable to determine the portal of entry and the sequence of fungal dissemination; no skin lesions were present at the time of admission. However, the multifocal nature, lung infiltration, and involvement of the middle cerebral artery distribution suggest hematogenous dissemination (8,9) after replication of airborne conidia within the respiratory tract.

Fungi cause >90% of brain abscesses in immunocompromised transplant patients with an associated mortality rate of 97% (10), despite aggressive surgery and antifungal therapy (9). Our patient was treated successfully with abscess drainage, antiretroviral therapy, and oral voriconazole, a novel antifungal triazole drug. Despite limited data available on voriconazole penetration into brain abscess cavities (9), this drug was clinically and radiologically effective in our patient.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patient for cooperating with our investigation, Pfizer Germany for providing voriconazole, and Heidemarie Losert and Elisabeth Antweiler for their excellent technical assistance.

References

(1.) Van Oorschot CAN. A revision of Chrysosporium and allied genera. Stud Mycol. 1980;1-89.

(2.) Pare JA, Sigler L, Hunter DB, Summerbell RC, Smith DA, Machin KL. Cutaneous mycoses in chameleons caused by the Chrysosporium anamorph of Nannizziopsis vriesii (Apinis) Currah. J Zoo Wildl Med. 1997;28:443-53.

(3.) Stillwell WT, Rubin BD, Axelrod JL. Chrysosporium, a new causative agent in osteomyelitis. A case report. Clin Orthop. 1984;190-2.

(4.) Roilides E, Sigler L, Bibashi E, Katsifa H, Flaris N, Panteliadis C. Disseminated infection due to Chrysosporium zonatum in a patient with chronic granulomatous disease and review of non-aspergillus fungal infections in patients with this disease. J Clin Microbiol. 1999:37:18-25.

(5.) Warwick A, Ferrieri P, Burke B, Blazar BR. Presumptive invasive Chrysosporium infection in a bone marrow transplant recipient. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1991;8:319-22.

(6.) Nichols DK, Weyant RS, Lamirande EW, Sigler L, Mason RT. Fatal mycotic dermatitis in captive brown tree snakes (Boiga irregularis). J Zoo Wildl Med. 1999;30:111-8.

(7.) Thomas AD, Sigler L, Peucker S, Norton JH, Nielan A. Chrysosporium anamorph of Nannizziopsis vriesii associated with fatal cutaneous mycoses in the salt-water crocodile (Crocodylus porosus). Med Mycol. 2002;40:143-51.

(8.) Calfee DP, Wispelwey B. Brain abscess. Semin Neurol. 2000;20:353-60.

(9.) Mathisen GE, Johnson JR Brain abscess. Clin Infect Dis. 1997:25:763-79.

(10.) Hagensee ME, Bauwens JE, Kjos B, Bowden RA. Brain abscess following marrow transplantation: experience at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, 1984-1992. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;19:402-8.

Address for correspondence: Christoph Steininger, University Clinic Eppendorf, Department of Medicine I, Infectious Diseases Unit, Martinistrasse 52, 20246 Hamburg, Germany; fax: 49-40-42803-6832; email: c.steininger@uke.uni-hamburg.de

Christoph Steininger, * Jan van Lunzen, * Kathrin Tintelnot, ([dagger]) Ingo Sobottka, * Holger Rohde, * Matthias Ansver Horstkotte, * and Hans-Jurgen Stellbrink *

* University Clinic Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany; and ([dagger]) Robert Koch-Institut, Mykologie, Berlin, Germany

COPYRIGHT 2005 U.S. National Center for Infectious Diseases

COPYRIGHT 2005 Gale Group