Dementia, or the progressive loss of cognitive function, becomes more prevalent with advancing age. In community- and practice-based studies, dementia has been found to affect 3 to 10 percent of persons 65 to 74 years of age, 19 to 30 percent of those 75 to 84 years of age, and 25 to 48 percent of those 85 years of age and older.[1,2]

Alzheimer's disease is the most common form of dementia in persons over 65 years of age. In the United States alone, 4 million persons have this progressive, degenerative, cementing illness. Alzheimer's disease has no known cure.

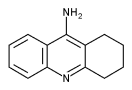

Tacrine (Cognex) is the first medication that has been shown to be beneficial in the palliative treatment of Alzheimer's disease. The decision to use tacrine to treat Alzheimer's disease should be based on sound diagnostic and therapeutic principles, including an appreciation of the pathophysiology of the illness, a determination of specific goals of therapy and an understanding of the pharmacologic properties of the drug. The modest therapeutic effects of this drug are likely to be augmented by continuous comprehensive care focused on maximizing patient function and providing support for caregivers.

Confirming the Diagnosis

Dementia is "a clinical state characterized by significant loss of function in multiple cognitive domains, not due to an impaired level of consciousness."[3] Because dementia affects multiple aspects of brain function, patients may present with changes in personality, a decline in functional ability, cognitive difficulties, anxiety or depression.

If patients or members of their families raise concerns about cognitive or behavior symptoms, a dementia evaluation should be considered. The purpose of this evaluation is to clarify the cause of dementia and to search for opportunities to improve cognitive function. A simultaneous search for conditions that mimic dementia is important, because 5 to 15 percent of patients with symptoms suggesting dementia have reversible cognitive impairment caused by alcohol, medications or depression.[4] The complete diagnostic evaluation must include a history from the patient and family members, an objective measure of cognitive ability, a focused neurologic examination and a number of laboratory tests.[3,5]

According to criteria in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV), listed in Table 1,[6] the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease not only requires documentation of deficits in memory for recent and remote events, but also evidence of cognitive disturbances related to language, learned motor behaviors and executive functioning (i.e., planning, organizing, abstracting, etc.). These deficits must represent a decline from a previous level of function, and they must impair social or occupational functioning. Furthermore, the cognitive loss must have a gradual onset, it must be progressive, and it must not be due to a systemic illness mimicking dementia.

It is important to note that the multiple structural and functional abnormalities in Alzheimer's disease limit the likelihood that treatments to correct neurotransmitter deficiencies can dramatically alter the course of the disease.

Measuring the Effectiveness of Therapy in Alzheimer's Disease

While the rationale for using tacrine to treat Alzheimer's disease is based on the importance of acetylcholine for memory function, patients with this illness have more extensive problems than just memory loss. Alzheimer's disease adversely affects multiple domains of cognition, behavior and psychosocial functioning. It follows that improved memory or cognitive test scores are not the only meaningful measures of the effectiveness of therapy. The progressive degenerative nature of Alzheimer's disease suggests that the benefits of therapy could also be measured by demonstrating improvements in a patient's cognitive, behavior or social function, or by a patient showing less deterioration than expected.

The primary goals in the treatment of a progressive neurologic disorder such as Alzheimer's disease are to maximize patient function and to support caregivers. Other treatment goals are determined according to caregiver concerns and each patient's unique problems. For instance, relevant caregiver outcomes might include reduced anxiety or depression and less caregiver time spent assisting the patient with the activities of daily living.[15] Important patient outcomes might include the control of disruptive behaviors or a decrease in the use of resources such as respite care or hospitalization.

Effectiveness of Tacrine

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved tacrine for use in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer's disease as evidenced by a score between 10 and 26 on the MMSE.

In four of eight placebo-controlled trials,[16-19] tacrine therapy produced statistically significant benefits in patients with Alzheimer's disease. One study[16] showed that in a dosage of 40 to 80 mg per day, tacrine reduced the rate at which cognitive function declined in patients with Alzheimer's disease. In another study,[17] in which tacrine was given in dosages ranging from 20 to 80 mg per day, patients demonstrated dose-related improvements in cognitive function and global measures of patient functioning. Yet another study[18] confirmed that tacrine in dosages up to 160 mg per day produced dose-related improvements in patient cognitive function and quality of life, as well as in global assessments of patient functioning by physicians and caregivers. In a two-year follow-up study[19] of patients who had responded to tacrine,[17] continued treatment in a dosage higher than 80 mg per day was associated with a reduced likelihood of nursing home placement.

These studies collectively show that tacrine can produce dose-related improvements in cognitive function and global measures of patient functioning. Both cognitive function and adverse cholinergic symptoms increase with higher doses of tacrine. The dropout rates in these studies were high, ranging from 42 to 73 percent, with clinical benefits documented in about one-half of the patients who were able to tolerate tacrine therapy.[17,18,20,21] While tacrine was shown to be superior to placebo, up to 15 percent of patients receiving placebo also showed significant improvement in some areas.[17]

Monitoring Tacrine Therapy

Patients who are receiving tacrine must be monitored for both clinical efficacy and adverse drug reactions. The studies on tacrine used measurements of cognition and behavior that are too cumbersome for routine use in primary care. To objectively measure patient response to treatment over time, family physicians can use the MMSE and the Functional Rating Scale for Symptoms of Dementia (FRSSD).[22] The latter is a brief scale of relevant abilities and behaviors related to dementia (Figure 1). It is most important to monitor the trends in MMSE and FRSSD scores over time. A declining MMSE score or a rising FRSSD score indicates that the dementia is progressing to a functionally more severe state. A positive response to therapy could be defined as an improvement or lack of deterioration in these scores. Physicians should also follow any changes in caregivers' most significant concerns about patient cognitive function and behavior.

Patients receiving tacrine therapy should be free of active liver disease. Liver transaminase levels increase in up to 50 percent of patients who are receiving this drug.[23] The serum alanine transaminase (ALT) concentration is the most commonly used marker for hepatic toxicity related to tacrine therapy. The drug may also raise aspartate transaminase or bilirubin levels.

Tacrine therapy should be discontinued if the serum ALT concentration is more than five times greater than the upper limit of normal. The ALT concentration usually returns to normal four to six weeks after the drug is discontinued. Once the ALT concentration is normalized, two-thirds of patients can tolerate a second trial of tacrine without elevations in enzyme levels. Tacrine should not be restarted if the bilirubin level is higher than 3 mg per dL (52 [mu]mol per L), if the ALT concentration is more than 10 times greater than the upper limit of normal or if the patient has hypersensitivity reactions such as a fever or rash.[20,23]

Cholinergic effects are primarily responsible for the side effects that necessitate the discontinuation of tacrine. Possible adverse reactions include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, dyspepsia, myalgia and worsening confusion or ataxia. Cholinergic symptoms may be decreased by lowering the dose of tacrine or by administering the drug with meals. Patients who have a history of peptic ulcer disease and those who are also receiving nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs should be monitored for occult gastric bleeding with serial stool guaiac tests and hemoglobin determinations. The cholinergic effects of tacrine may cause bradycardia, may exacerbate asthma or may worsen the symptoms of Parkinson's disease.[20,23]

Because tacrine is metabolized by the cytochrome P450 system, it raises theophylline concentrations. Cimetidine (Tagamet) raises serum tacrine concentrations. Tacrine has not caused adverse pharmacokinetic effects in patients who are also receiving digoxin (Lanoxin), warfarin (Coumadin) or diazepam (Valium).[20] Tacrine excretion is unaffected by renal insufficiency.

Titrating the Tacrine Dose

Tacrine should be given in four doses that are spaced regularly throughout the day, preferably between meals. The initial dosage is 10 mg four times daily for six weeks. During this period, bilirubin and liver transaminase levels are monitored every other week. If the ALT level is less than three times the upper limit of normal, the dosage is increased to 20 mg four times daily. The dosage can be titrated upward by 40 mg per day every six weeks. The maximum daily dosage of tacrine is 160 ma. While higher dosages produce greater beneficial effects, more adverse effects also occur.

The ALT concentration should be monitored every other week for at least the first 16 weeks of therapy and for six weeks following any dosage increase. The ALT concentration should also be monitored if it is two times the upper level of normal. When the dosage is stable and the ALT level is less than two times the upper limit of normal, monitoring intervals may be increased to every month for two months and then increased to every three months (Figure 2).

Final Comment

Tacrine is the first medication that has been shown to improve cognitive function in patients with Alzheimer's disease. The magnitude of the benefit from three months of treatment is approximately equivalent to postponing the inevitable cognitive decline expected over six months.[17,20,21] When patients showing a benefit from tacrine were switched to placebo, cognitive function declined to baseline. The implication is that the benefits of tacrine are lost if the drug is discontinued.[16] Unfortunately, for every four Alzheimer's patients who are treated with tacrine, only one shows clear benefit. Investigators continue to search for ways to prospectively identify patients who are more likely to respond to tacrine.

Once a patient's function has been optimized using nonpharmacologic measures, the patient, the family members and the family physician may consider a trial of tacrine to improve cognitive and behavioral function. One month of therapy and current recommended monitoring cost about $300. The value of tacrine therapy depends on whether the patient and his or her family believe that the cost and potential adverse effects of tacrine are justified by their impressions of the global benefits of therapy and the objective measurements of improvements in cognition, behavior or psychosocial functioning. An article previously published in American Family Physician provides patients and their families with important information about the effects of tacrine.[24]

The author thanks Margaret Abernathy for her assistance in the preparation of the manuscript.

Figure 1 adapted from Hutton JT, Dippel RL, Loewenson RB, Mortimer JA, Christians BL. Predictors of nursing home placement of patients with Alzheimer's disease. Tex Med 1985;81:40-3. Used with permission.

[Figures 1 to 2 ILLUSTRATION OMITTED]

REFERENCES

[1.] Evans DA, Funkenstein HH, Albert MS, Scherr PA, Cook NR, Chown MJ, et al. Prevalence of Alzheimer's disease in a community population of older persons. Higher than previously reported. JAMA 1989;262:2551-6. [2.] Callahan CM, Hendrie HC, Tierney WM. Documentation and evaluation of cognitive impairment in elderly primary care patients. Ann Intern Med 1995;122:422-9. [3.] Practice parameter for diagnosis and evaluation of dementia. Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology Neurology 1994;44:2203-6. [4.] Clarfield AM. The reversible dementias: do they reverse? Ann Intern Med 1988;109:476-86. [5.] Fleming KC, Adams AC, Petersen RC. Dementia: diagnosis and evaluation. Mayo Clin Proc 1995;70: 1093-107. [6.] Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association, 1994:142-3. [7.] Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. "Mini-mental state." A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975;12:189-98. [8.] Kukull WA, Larson EB, Teri L, Bowen J, McCormick W, Pfanschmidt ML. The Mini-Mental State Examination score and the clinical diagnosis of dementia. J Clin Epidemiol 1994;47:1061-7. [9.] Larson EB, Reifler BV, Featherstone HJ, English DR. Dementia in elderly outpatients: a prospective study. Ann Intern Med 1984;106:417-23. [10.] Overman W Jr, Stoudemire A. Guidelines for legal and financial counseling of Alzheimer's disease patients and their families. Am J Psychiatry 1988 145:1495-500. [11.] Robinson A, Spencer B, White L, eds. Understanding difficult behaviors: some practical suggestions for coping with Alzheimer's disease and related illnesses. Ypsilanti, Mich.: Geriatric Education Center of Michigan, 1989. [12.] Gallo JJ, Franch MS, Reichel W. Dementing illness: the patient, caregiver and community. Am Fam Physician 1991;43:1669-75. [13.] Patel SV. Pharmacotherapy of cognitive impairment in Alzheimer's disease: a review. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 1995;8:81-95. [14.] Wagstaff AJ, McTavish D. Tacrine. A review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties, and therapeutic efficacy in Alzheimer's disease. Drugs Aging 1994;4:510-40 [Published erratum appears in Drugs Aging 1994;5:95]. [15.] Clipp EC, Moore MJ. Caregiver time use: an outcome measure in clinical trial research on Alzheimer's disease. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1995;58: 228-36. [16.] Davis KL, Thal LJ, Gamzu ER, Davis CS, Woolson RF, Gracon SI, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter study of tacrine for Alzheimer's disease. The Tacrine Collaborative Study Group. N Engl J Med 1992;327:1253-9. [17.] Farlow M, Gracon SI, Hershey LA, Lewis KW, Sadowsky CH, Dolan-Ureno J. A controlled trial of tacrine in Alzheimer's disease. The Tacrine Study Group. JAMA 1992;268:2523-9. [18.] Knapp MJ, Knopman DS, Solomon PR, Pendlebury WW, Davis CS, Gracon SI. A 30-week randomized controlled trial of high-dose tacrine in patients with Alzheimer's disease. The Tacrine Study Group. JAMA 1994;271:985-91. [19.] Knopman D, Schneider L, Davis K, Talwalker S, Smith F, Hoover T, et al. Long-term tacrine (Cognex) treatment: effects on nursing home placement and mortality. Neurology (In press). [20.] Crismon ML. Tacrine: first drug approved for Alzheimer's disease. Ann Pharmacother 1994,28: 744-51. [21.] Winker MA. Tacrine for Alzheimer's disease. Which patient, what dose? [Editorial]. JAMA 1994;271:1023-4. [22.] Hutton JT, Dippel RL, Loewenson RB, Mortimer JA, Christians BL. Predictors of nursing home placement of patients with Alzheimer's disease. Tex Med 1985;81:40-3. [23.] Watkins PB, Zimmerman HJ, Knapp MJ, Gracon SI, Lewis KW. Hepatotoxic effects of tacrine administration in patients with Alzheimer's disease. JAMA 1994;271;992-8. [24.] Manning FC. Tacrine therapy for the dementia of Alzheimer's disease. Am Fam Physician 1994;50: 819-23,825-6.

The Author

WILLIAM D. SMUCKER, M.D. is associate professor of family medicine at Northeastern Ohio Universities College of Medicine, Rootstown, associate director of the Family Practice Center of Akron at Summa Health System and medical director at the Altenheim Nursing Home, Strongsville, Ohio. Dr. Smucker received his medical degree from Case Western Reserve University Medical School, Cleveland, and completed a residency in family practice at the Family Practice Center of Akron, Akron City Hospital, Summa Health System.

Address correspondence to William D. Smucker, M.D., Family Practice Center of Akron, 75 Arch St., Suite 2, Akron, OH 44304.

COPYRIGHT 1996 American Academy of Family Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group