Abstract

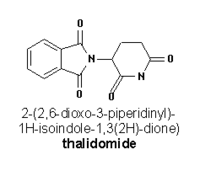

Thalidomide has gained an infamous history due to severe birth defects observed in patients who had taken the drug to control nausea during pregnancy. (1) The medication was withdrawn from the market because of its teratogenicity, but was approved by the FDA in 1998 for the treatment of erythema nodosum leprosum. However, thalidomide has been employed with success by dermatologists for a host of off-label uses including the treatment of lichen planus. (2) Currently, no clinical trials or studies exist to evaluate the efficacy of using thalidomide to treat lichen planus, but case reports have been published in the medical literature supporting its therapeutic benefits. (3-6) TNF-[alpha] is among the many cytokines that have been implicated in the pathogenicity of lichen planus. It is thought that thalidomide acts

**********

Case Report

We describe a patient who experienced complete resolution of generalized lichen planus within 3 months of initiating treatment with thalidomide. A 43-year-old female with diabetes mellitus and hepatitis C was referred to our clinic with a 6-month history of a skin eruption. The patient had previously been diagnosed with lichen planus and was treating the condition with high potency topical corticosteroids without significant improvement. She was not a good candidate for systemic steroids because of her diabetes and hepatitis C. On physical examination, the patient exhibited countless flat-topped, polygonal, violaceous papules distributed among her trunk and extremities (Figures 1, 2, and 3). She was also found to have lacy white patches on her buccal mucosa characteristic of Wickham's striae. Thalidomide therapy was initiated at a dose of 100 mg nightly. The patient had previously had a hysterectomy, which ensured that she would not become pregnant while taking thalidomide. Topical steroids were continued in conjunction with thalidomide.

[FIGURE 1 OMITTED]

[FIGURE 2 OMITTED]

[FIGURE 3 OMITTED]

When the patient returned for her 1- and 2-month follow-up office visits, she denied having any side effects related to the medication. The papules were noticeably flatter than on her initial visit, and the color was fading from purple to brown. After 3 months of thalidomide administration, the patient was cleared of skin lesions, and only post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation was evident (Figures 4, 5, and 6). Thalidomide was discontinued, and the patient was advised to return if she developed any recurrences. One year has passed without a relapse.

Because there are relatively few case reports in the literature detailing the therapeutic efficacy of thalidomide, more investigation into thalidomide as a treatment for lichen planus would be useful. Certain patients seem to have a better response to the medication than others. Naafs and Faber (3) described resolution of oral erosive disease in one patient, while another patient with generalized lichen planus had no improvement during administration of thalidomide. Perez et al (4) reported a case of generalized lichen planus with penile lesions where clearance was achieved without difficulty. Dereure et al (5) and Camisa and Popovsky (6) described 3 other patients with severe disabling lichen planus who were resistant to therapy with corticosteroids, phototherapy, etretinate, azathioprine, and cyclosporine. In each of the 3 cases, the patients experienced excellent responses to thalidomide therapy with complete resolution of the eruptions. Lichen planopilaris has also been successfully treated with thalidomide. (9,10)

[FIGURE 4 OMITTED]

[FIGURE 5 OMITTED]

Commonly encountered side effects of thalidomide administration include sedation, constipation, and headache. These side effects are often dependent on dosage. Therefore, it is beneficial to begin therapy at the lowest dosage possible and titrate to efficacy to keep the risks of undesired side effects low. (8) However, the side effect most likely to limit therapy with thalidomide is peripheral neuropathy. There has been controversy in the literature as to whether or not this is a dose-dependent side effect, but it is clear that all patients on thalidomide should be monitored closely for development of peripheral neuropathy. Treatment should be discontinued if patients complain of numbness or tingling in their hands and/or feet, muscle cramps, or proximal muscle weakness. (11,12) In addition, because thalidomide is a severe teratogen, care must be taken when selecting patients to treat with this therapy. Our patient had undergone a hysterectomy; however, in patients capable of childbearing, strict adherence to contraception guidelines must be ensured. (13) The manufacturer of thalidomide, Celgene, has a program called the System for Thalidomide Education and Prescribing Safety (STEPS), which all physicians prescribing thalidomide must follow. Frequent pregnancy testing and writing prescriptions for no more than a 28-day regimen requires patients to have close follow-up while taking the medication. Males taking thalidomide should also practice contraception with their partners, as thalidomide has been found in semen samples of men taking the drug. (14)

[FIGURE 6 OMITTED]

Although it remains unclear exactly what mechanism thalidomide effects to bring about resolution of the skin lesions of lichen planus, the medication has sufficient anecdotal evidence to support its consideration as a valid treatment option. We believe that in patients who have not responded to other, more traditional modalities, thalidomide may be an efficacious and relatively safe (with proper monitoring and precautions) treatment for refractory lichen planus.

References

1. Stirling DI. Thalidomide and its impact in dermatology. Semin in Cutan Med Surg. 1998;17:231-42.

2. Calabrese L, Fleischer AB. Thalidomide: current and potential clinical applications. Am J Med. 2000;108:487-95.

3. Naafs B, Faber WR. Thalidomide therapy: an open trial. Int J Dermatol. 1985;24:131-4.

4. Perez Alfonzo R, Weiss E, Piquero Martin J, Rondon Lugo A. Generalized lichen planus with erosive lesions of the penis, treated with thalidomide. Report of a case and review of the literature. Med Cutan Ibero Lat Am. 1987;15:321-6.

5. Dereure O, Basset-Seguin N, Guilhou JJ. Erosive lichen planus: dramatic response to thalidomide. Arch Dermatol. 1996;118:536.

6. Camisa C, Popovsky JL. Effective treatment of oral erosive lichen planus with thalidomide. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1442-3.

7. Sampaio EP, Sarno EN, Galilly R, Cohn ZA, Kaplan G. Thalidomide selectively inhibits tumor necrosis factor alpha production by stimulated human monocytes. J Exp Med. 1991;173:699-703

8. Tseng S, Pak G, Washenik K, Pomeranz MK, Shupack JL. Rediscovering thalidomide: A review of its mechanism of action, side effects, and potential uses. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:969-79.

9. George SJ, Hsu S. Lichen planopilaris treated with thalidomide. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001; 45: 965-6.

10. Boyd AS, King LE. Thalidomide-induced remission of lichen planopilaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002; 47:967-8.

11. Hess CW, Hunziker T, Kupfer A, Lundin HP. Thalidomide induced peripheral neuropathy. A prospective clinical, neurophysiological and pharmacogenetic evaluation. J Neurol. 1986;233:83-9.

12. Chaudhry V, Cornblath DR, Corse A, Freimer M, Simmons-O'Brien E, Vogelsang G. Thalidomide-induced neuropathy. Neurology. 2002;59:1872-5.

13. McBride WG. Thalidomide embryopathy. Teratology. 1977;16:79-82.

14. Teo SK, Harden JL, Burke AB, Ong F. Thalidomide is distributed into human semen after oral dosing. Drug Metab Dispos. 2001;29:1355-57.

Jennifer L. Maender MD, Ravi S. Krishnan MD, Tiffany A. Angel MD, Sylvia Hsu MD

Department of Dermatology, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas

COPYRIGHT 2005 Journal of Drugs in Dermatology

COPYRIGHT 2005 Gale Group