Definition

Antibiotic-associated colitis is an inflammation of the intestines that sometimes occurs following antibiotic treatment and is caused by toxins produced by the bacterium Clostridium difficile.

Description

Antibiotic-associated colitis, also called antibiotic-associated enterocolitis, can occur following antibiotic treatment. The bacteria Clostridia difficile are normally found in the intestines of 5% of healthy adults, but people can also pick up the bacteria while they are in a hospital or nursing home. In a healthy person, harmless resident intestinal bacteria compete with each other for food and places to "sit" along the inner intestinal wall. When antibiotics are given, most of the resident bacteria are killed. With fewer bacteria to compete with, the normally harmless Clostridia difficile grow rapidly and produce toxins. These toxins damage the inner wall of the intestines and cause inflammation and diarrhea.

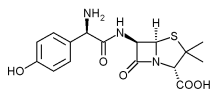

Although all antibiotics can cause this disease, it is most commonly caused by clindamycin (Cleocin), ampicillin (Omnipen), amoxicillin (Amoxil, Augmentin, or Wymox), and any in the cephalosporin class (such as cefazolin or cephalexin). Symptoms of the condition can occur during antibiotic treatment or within four weeks after the treatment has stopped.

In approximately half of cases of antibiotic-associated colitis, the condition progresses to a more severe form of colitis called pseudomembranous enterocolitis in which pseudomembranes are excreted in the stools. Pseudomembranes are membrane-like collections of white blood cells, mucus, and the protein that causes blood to clot (fibrin) that are released by the damaged intestinal wall.

Causes & symptoms

Antibiotic-associated colitis is caused by toxins produced by the bacterium Clostridium difficile after treatment with antibiotics. When most of the other intestinal bacteria have been killed, Clostridium difficile grows rapidly and releases toxins that damage the intestinal wall. The disease and symptoms are caused by these toxins, not by the bacterium itself.

Symptoms of antibiotic-associated colitis usually begin four to ten days after antibiotic treatment has begun. The early signs and symptoms of this disease include lower abdominal cramps, an increased need to pass stool, and watery diarrhea. As the disease progresses, the patient may experience a general ill feeling, fatigue, abdominal pain, and fever. If the disease proceeds to pseudomembranous enterocolitis, the patient may also experience nausea, vomiting, large amounts of watery diarrhea, and a very high fever (104-105°F/40-40.5°C). Complications of antibiotic-associated colitis include severe dehydration, imbalances in blood minerals, low blood pressure, fluid accumulation in deep skin (edema), enlargement of the large intestine (toxic megacolon), and the formation of a tear (perforation) in the wall of the large intestine.

Clostridium difficile is easily spread from person to person in hospitals and nursing homes. The following individuals are most at-risk for developing this disease:

- The elderly

- Severely ill individuals

- Individuals with weakened or suppressed immune systems (immunocompromised)

- Individuals with poor hygiene

- Individuals who have been hospitalized for a long period of time.

The Clostridium difficile toxin is found in the stools of persons older than 60 years of age 20-100 times more frequently than in the stools of persons who are 10-20 years old. As a result, the elderly are much more prone to developing antibiotic-associated colitis than younger individuals.

Diagnosis

Antibiotic-associated colitis can be diagnosed by the symptoms and recent medical history of the patient, by a laboratory test for the bacterial toxin, and/or by using a procedure called endoscopy.

If the diarrhea and related symptoms occurred after the patient received antibiotics, antibiotic-associated colitis may be suspected. A stool sample may be analyzed for the presence of the Clostridium difficile toxin. This toxin test is the preferred diagnostic test for antibiotic-associated colitis. One frequently used test for the toxin involves adding the processed stool sample to a human cell culture. If the toxin is present in the stool sample, the cells die. It may take up to two days to get the results from this test. A simpler test, which provides results in two to three hours, is also available. Symptoms and toxin test results are usually enough to diagnose the disease.

Another tool that may be useful in the diagnosis of antibiotic-associated colitis, however, is a procedure called an endoscopy that involves inserting a thin, lighted tube into the rectum to visually inspect the intestinal lining. Two different types of endoscopy procedures, the sigmoidoscopy and the colonoscopy, are used to view different parts of the large intestine. These procedures are performed in a hospital or doctor's office. Patients are sedated during the procedure to make them more comfortable and are allowed to go home after recovering from the sedation.

Treatment

Diarrhea, regardless of the cause, is always treated by encouraging the individual to replace lost fluids and prevent dehydration. One method to treat antibiotic-associated colitis is to simply stop taking the antibiotic that caused the disease. This allows the normal intestinal bacteria to repopulate the intestines and inhibits the overgrowth of Clostridium difficile. Many patients with mild disease respond well to this and are free from diarrhea within two weeks. It is important, however, to make sure that the original disease for which the antibiotics were prescribed is treated.

Because of the potential seriousness of this disease, most patients are given another antibiotic to control the growth of the Clostridium difficile, usually vancomycin (Vancocin) or metronidazole (Flagyl or Protostat). Both are designed to be taken orally four times a day for 10-14 days. Upon finishing antibiotic treatment, approximately 15-20% of patients will experience a relapse of diarrhea within one to five weeks. Mild relapses can go untreated with great success, however, severe relapses of diarrhea require another round of antibiotic treatment. Instead of further antibiotic treatment, a cholestyramine resin (Questran or Prevalite) may be given. The bacterial toxins produced in the intestine stick to the resin and are passed out with the resin in the stool. Unfortunately, however, vancomycin also sticks to the resin, so these two drugs cannot be taken at the same time. Serious disease may require hospitalization so that the patient can be monitored, treated, and rehydrated.

Alternative treatment

The goal of alternative treatment for antibiotic-associated enterocolitis is to repopulate the intestinal environment with microorganisms that are normal and healthy for the intestinal tract. These microorgansisms then compete for space and keep the Clostridium difficile from over-populating.

Several types of supplements can be used. Supplements containing Lactobacillus acidophilus, the bacteria commonly found in yogurt and some types of milk, Lactobacillus bifidus, and Streptococcus faecium, are available in many stores in powder, capsule, tablet, and liquid form. Acidophilus also acts as a mild antibiotic, which helps it to reestablish itself in the intestine, and all may aid in the production of some B vitamins and vitamin K. These supplements can be taken individually and alternated weekly or together following one or more courses of antibiotics.

Prognosis

With appropriate treatment and replenishment of fluids, the prognosis is generally excellent. One or more relapses can occur. Very severe colitis can cause a tear (perforation) in the wall of the large intestine that would require major surgery. Perforation of the intestine can cause a serious abdominal infection. Antibiotic-associated colitis can be fatal in people who are elderly and/or have a serious underlying illness, such as cancer.

Prevention

There are no specific preventative measures for this disease. Good general health can reduce the chance of developing a bacterial infection that would require antibiotic treatment and the chance of picking up the Clostridia bacteria. Maintaining good general health can also reduce the seriousness and length of the condition, should it develop following antibiotic therapy.

Key Terms

- Colitis

- Inflammation of the colon.

- Edema

- Fluid accumulation in a tissue.

- Endoscopy

- A procedure in which a thin, lighted instrument is inserted into the interior of a hollow organ, such as the rectum and used to visually inspect the inner intestinal lining.

- Fibrin

- A fibrous blood protein vital to coagulation and blood clot formation.

- Rectum

- The last part of the intestine. Stool passes through the rectum and out through the anal opening.

- Toxic megacolon

- Acute enlargement or dilation of the large intestine.

Further Reading

For Your Information

Periodicals

- Fekety, R., and A.B. Shah. "Diagnosis and Treatment of Clostridium difficile Colitis." Journal of the American Medical Association, 269 (1993): 71+.

- Kelly, Ciaran P., Charalabos Pothoulakis, and J. Thomas LaMont. "Clostridium difficile Colitis." The New England Journal of Medicine, 330 (January 27, 1994): 257+.

Other

- Mayo Health Oasis. 1998. http://www.mayohealth.org (5 March 1998).

Gale Encyclopedia of Medicine. Gale Research, 1999.