Steriod slackens pace of muscular dystrophy

A powerful steroid has poved its mettle as the first drug to slow progressive muscle weakening in youngsters with Duchenne's muscular dystrophy. Although the drug, called prednisone, carries serious side effects, researchers believe it may ultimately point the way to an equally effective but safer treatment.

"For the first time, we have a long-term study that shows [prednisone's] efficacy," says Gerald M. Fenichel of Vanderbilt University in Nashville, who presented the results this week at the American Academy of Neurology meeting in Boston. He cautions, however, that the drug cannot rid patients of the disease. "Prednisone is not a cure," he says.

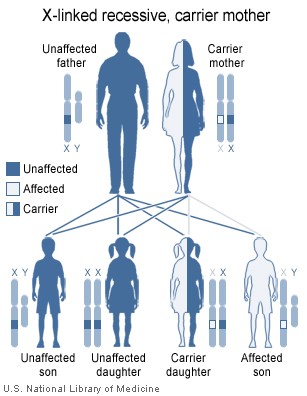

One out of every 3,500 male infants in the United States has inherited a defective gene that causes Duchenne's muscular dystrophy. At about age 3, afflicted children develop a swaying or waddling motion when they walk. From that seemingly innocent early stage, the disease advances until weakened muscles can no longer hold the body upright. Even with physical theraphy, most victims need a wheelchair by age 12, and most die of heart or lung complications by age 20.

Several years ago, a study directed by Daniel B. Drachman of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore hinted at prednisone's potential in boys with Duchenne's -- the most serious form of muscular dystrophy (SN: 8/22/87, p.120). Fenichel and his colleagues have now confirmed that early promise in a multicenter trial of 89 Duchenne's patients ranging from 7 to 14 years of age.

In a year-long experiment, Fenichel's team found that a daily doe of 0.75 milligrams of prednisone per kilogram of body weight seemed to offer the best short at fighting the muscle-sapping disorder. After that initial phase, they continued to treat the boys but had to lower the maximum dose for some patients because of harsh side effects.

Three years later, the 49 boys taking the highest daily doses (at least 0.65 mg/kg) showed the most favorable response, Fenichel reports. Their muscle strength (measured by weight-lifting tests) declined by an average of 0.017 unit per year, whereas the boys on lower doses lost about 0.164 unit per year. Altough the study did not include a control group, Fenichel says participants showed a clear benefit compared with Duchenne's patients in general, who typically lose about 0.4 unit per year. Some volunteers actually gained muscle strength, he adds -- an improvement readily noted by their parents.

"This study reports an apparent slowing of the progression of the disease over a period of time," comments Lawrence Z. Stern of the Muscular Dystrophy Association in Tucson, Ariz. Nonetheless, he calls the results "modest." Even for children who improve, he says, the drug may delay the need for a wheelchair by only weeks or months. Drachman, on the other hand, asserts that careful prednisone treatment can postpone wheelchair confinement by two years or more.

The Muscular Dystrophy Association, citing safety concerns, does not recommend prednisone treatment. However, says Stern, if researchers could unlock the secret of the steroid's dystrophy-fighting effect, they might someday design less toxic drug treatments.

To test a hypothesis that prednisone works by suppressing a muscle-ravaging immune response, the same researchers conducted a separate study of 99 Duchenne's patients. An immunosuppressant drug called azathioprine failed to slow muscle wasting, but prednisone again showed its protective effect. Robert C. Griggs of the University of Rochester in New York, who reported the results at the Boston meeting, says this means the researchers must look beyond the immunity hypothesis.

COPYRIGHT 1991 Science Service, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group