While dwarfism is sometimes used to describe achondroplasia, a condition characterized by short stature and disproportionately short arms and legs, it is also used more broadly to refer to a variety of conditions resulting in unusually short stature in both children and adults. In some cases physical development may be disproportionate, as in achondroplasia, but in others the parts of the body develop proportionately. Short stature may be unaccompanied by other symptoms, or it may occur together with other problems, both physical and mental. Adult males under 5 ft (1.5 m) tall and females under 4 ft 8 in (1.4 m) are classified as short-statured. Children are considered unusually short if they fall below the third percentile of height for their age group. In 1992 there were about five million people of short stature (for their age) living in the United States, of which 40% were under the age of 21.

Some prenatal factors known to contribute to growth retardation include a variety of maternal health problems, including toxemia, kidney and heart disease, infections such as rubella, and maternal malnutrition. Maternal age is also a factor (adolescent mothers are prone to have undersize babies), as is uterine constraint (which occurs when the uterus is too small for the baby). Possible causes that center on the fetus rather than the mother include chromosomal abnormalities, genetic and other syndromes that impair skeletal growth, and defects of the placenta or umbilical cord. Environmental factors that influence intrauterine growth include maternal use of drugs (including alcohol and tobacco). Some infants who are small at birth (especially twins) may attain normal stature within the first year of life, while others remain small throughout their lives.

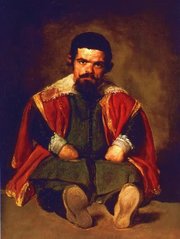

The four most common causes of dwarfism in children are achondroplasia, Turner syndrome, inadequate pituitary function, and lack of emotional or physical nurturance. Achondroplasia (short-limbed dwarfism) is a genetic disorder that impairs embryonic development, resulting in abnormalities in bone growth and cartilage development. It is one of a class of illnesses called chondrodystrophies, all of which involve cartilage abnormalities and result in short stature. In achondroplasia, the long bones fail to develop normally, making the arms and legs disproportionately short and stubby (and sometimes curved). Overly long fibulae (one of two bones in the lower leg) cause the bowlegs that are characteristic of the condition. In addition, the head is disproportionately large and the bridge of the nose is depressed. Persons with achondroplasia are between 3-5 ft (91-152 cm) tall and of normal intelligence. Their reproductive development is normal, and they have greater than normal muscular strength. The condition occurs in 1 out of every 10,000 births, and its prevalence increases with the age of the parents, especially the father. Achondroplasia can be detected through prenatal screening. Many infants with the condition are stillborn. Turner syndrome is a chromosomal abnormality occurring only in females in whom one of the X chromosomes is missing or defective. Girls with Turner syndrome are usually between 4.5-5 ft (137-152 cm) high. Their ovaries are undeveloped, and they do not undergo puberty. Besides short stature, other physical characteristics include a stocky build and a webbed neck.

Endocrine and metabolic disorders are another important cause of growth problems. Growth can be impaired by conditions affecting the pituitary, thyroid, parathyroid, and adrenal glands (all part of the endocrine system). Probably the best known of these conditions is growth hormone deficiency, which is associated with the pituitary and hypothalamus glands. If the deficiency begins prenatally, the baby will still be of normal size and weight at birth but will then experience slowed growth. Weight gain still tends to be normal, leading to overweight and a higher than average proportion of body fat. The facial structures of children with this condition are immature, making them look younger than their actual age. Adults in whom growth hormone deficiency has not been treated attain a height of only about 2.5 ft (76 cm). They also have high-pitched voices, high foreheads, and wrinkled skin. Another endocrine disorder that can interfere with growth is hypothyroidism, a condition resulting from insufficient activity of the thyroid gland. Affecting 1 in 4,000 infants born in the United States, it can have a variety of causes, including underdevelopment, absence, or removal of the thyroid gland, lack of an enzyme needed for adequate thyroid function, iodine deficiency, or an underactive pituitary gland. In addition to retarding growth, it can cause mental retardation if thyroid hormones are not administered in the first months of an infant's life. If the condition goes untreated, it causes impaired mental development in 50% of affected children by the age of six months.

About 15% of short stature in children is caused by chronic diseases, of which endocrine disorders are only one type. Many of these conditions do not appear until after the fifth year of life. Children with renal disease often experience growth retardation, especially if the condition is congenital. Congenital heart disease can cause slow growth, either directly or through secondary problems. Short stature can also result from a variety of conditions related to inadequate nutrition, including malabsorption syndromes (in which the body is lacking a substance--often an enzyme--necessary for proper absorption of an important nutrient), chronic inflammatory bowel disorders, caloric deficiencies, and zinc deficiency. A form of severe malnutrition called marasmus retards growth in all parts of the body, including the head (causing mental retardation as well). Marasmus can be caused by being weaned very early and not adequately fed afterwards; if the intake of calories and protein is limited severely enough, the body wastes away. Although the mental and emotional effects of the condition can be reversed with changes in environment, the growth retardation it causes is permanent. On occasion, growth retardation may also be caused solely by emotional deprivation.

Since growth problems are so varied, there is a wide variety of treatments for them, including nutritional changes, medications to treat underlying conditions, and, where appropriate, hormone replacement therapy. More than 150,000 children in the United States receive growth hormone therapy to remedy growth retardation caused by endocrine deficiencies. Growth hormone for therapeutic purposes was originally derived from the pituitary glands of deceased persons. However, natural growth hormone, aside from being prohibitively expensive, posed health hazards due to contamination. In the 1980s, men who had received growth hormone therapy in childhood were found to have developed Kreuzfeldt-Jakob disease, a fatal neurological disorder. Since then, natural growth hormone has been replaced by a biosynthetic hormone that received FDA approval in 1985.

Gale Encyclopedia of Childhood & Adolescence. Gale Research, 1998.