The discovery of mutant genes for common diseases such as Alzheimer's, cancer, and diabetes occurs so frequently these days that it is almost in danger of passing without comment. Sometimes, though, geneticists head off in search of stranger stuff.

At Baylor College of Medicine in Houston last June, physician Luis Figuera and his colleagues hounded down the location of a gene for congenital generalized hypertrichosis, sometimes called werewolf syndrome. The gene, believed to be on a small region of the X chromosome, causes thick, abundant hair to sprout on the upper body and all parts of the face, including the nose, cheeks, forehead, and eyelids, of affected males. So rare is this syndrome that all 19 currently known cases occur in one Mexican family. Figuera hopes that pinpointing and cloning the gene for CGH could one day help researchers understand and treat baldness.

CGH is also intriguing as an example of an atavistic mutation--one that reactivates a gene whose function was suppressed during the course of human evolution. As with multiple nipples, a rare throwback to the days when our ancestors may have had more than one pair, this facial furriness may be caused by a gene that in most of us is kept under lock and key.

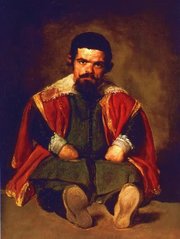

Pycnodysostosis, a hereditary form of dwarfism, is also a rare disease, occurring in fewer than 1 out of 100,000 people. This past June geneticists Mihael Polymeropoulos of the National Center for Human Genome Research in Bethesda, Maryland, and Bruce Gelb of the Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York traced the gene for it to chromosome 1. The gene appears to play a pivotal role in the function of the osteoclasts, cells that continuously dissolve bone and regenerate it; when the gene is mutated, bones become abnormally thick, fragile, and liable to fracture. Other symptoms of the disease include an open fontanel, or soft, unfused spot on the skull, short fingers and toes, and a receding chin.

There is a famous--but disputed--case of pycnodysostosis: Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, painter of bars, brothels, and cabarets in nineteenth-century Paris. "We know for a fact that he was dwarfed," says Gelb. "And he always wore a hat"--as in thsi photo. "Was that because he was covering up an abnormal head where the bones hadn't fused properly?" The painter incurred several serious fractures before dying at the young age of 36. His aristocratic parents were first cousins, so they might both have passed on the recessive gene. Still, his chin appears normal in photos, and there is no evidence that he had excessively short toes or fingers. "If one had the luxury of examining him, one should be able to tell for sure," says Gelb. So far, however, the Toulouse-Lautrec family has been understandably reluctant to unearth the artist.

A third disorder investigated in 1995 is not uncommon, but it's uncommon for geneticists to be studying it: bed-wetting. Severe "nocturnal enuresis," characterized by three or more bed-wetting episodes per week in children older than age seven, affects some 7 percent of the population. Remedies proposed through the ages include drinking bouillon from the boiled combs of hens and equipping the bed with alarm clocks triggered by damp sheets. Bed-wetting has often been considered a behavioral problem--and it has often been a source of shame and mortification to children.

But this past July Hans Eiberg of the Danish Center for Genome Research in Copenhagen said he'd found 11 families in whom a propensity for bed-wetting appeared to be inherited, affecting 50 percent of the children. The gene, says Eiberg, is on chromosome 13, and though he has yet to pinpoint it, he suspects it may be involved in controlling either the amount of urine produced at night or the muscles of the bladder. Eiberg hopes his discovery will lead to a greater understanding of this ailment. "Nobody believed that some cases are genetic," he says. "But this shows that it's not necessary to blame the children."

COPYRIGHT 1996 Discover

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group