Vanessa Sawyer can't pinpoint what pushed her over the edge. But she recalls the day her family made the difficult decision to commit her to a psychiatric ward. "I was at my parents' home in Sacramento," she recalls. "My mind was racing. It was near Martin Luther King, Jr.'s birthday. Suddenly I started telling everyone that I was the reincarnation of Rev. King. After my sister, Valerie, took me to the hospital, I saw a birth announcement on a bulletin board. I thought, I can die now. By this time, I believed that I was the Messiah who had come to save the children, and that the little newborn was here to take my place."

Vanessa, 41, has finally climbed out of the abyss that began to engulf her 15 years ago. Today she's a mother, tax consultant, author and public speaker. But she's the first to admit that her mental illness, bipolar affective disorder (also known as manic-depressive disorder), took her to the brink. It is a disease characterized by extreme mood swings, racing thoughts and speech, reckless behavior, irritability, grandiosity and psychosis.

Victims of the illness also struggle with a profound loss of energy, feelings of hopelessness, sleep disturbances and thoughts of suicide in the depressive phase. More than 2 million Americans suffer from some form of the disorder.

Vanessa's family often felt they were in the abyss with her. And they tried to cope with their own feelings of sadness, guilt, resentment and shame. Living with a loved one who is mentally ill is challenging for most families, but perhaps more so for African-Americans, who are also struggling with issues related to race and class.

Sometimes we don't recognize the symptoms of mental illness; other times, we're in denial, even after diagnosis. "Big Mama really showed out," we say, when the reality is that her out-of-control behavior may indicate bipolar disorder. "Junior doesn't say much," we observe, not wanting to admit that his catatonic stare may really be a sign of schizophrenia. "She's just quiet," we say of Baby Sis, whose joyless existence suggests clinical depression. We'll whisper about drug addicts, shopaholics and promiscuous members of the family, even those who've been incarcerated, without digging deep enough to find out if their behavior may be a symptom of mental illness.

But denial doesn't make mental illness disappear. Instead, it only compounds the problem because it prevents people from getting the help they need. "There are many undiagnosed bipolars who self-medicate with alcohol, drugs and sex," says Renee Lee-Ferguson, a psychotherapist in Atlanta. But the prognosis isn't always dire. "Bipolars can thrive," says Lee-Ferguson, who counseled Vanessa at a critical point in her treatment. "They can be as successful as anyone if they take their medication."

A Slow Unraveling

Vanessa's first inkling that she had a problem came when she was a student at California State University, Sacramento, in 1981. She was devastated when a man she was dating broke up with her. Then she began having trouble concentrating on her studies. "Nothing would stay in my brain," she says. She had been on the dean's list her freshman year, "but by the second year I had to repeat every class." She also became antisocial and slept a lot. "I was taking a bath only once or twice a week," she continues. "I had days of just thinking about dying. I didn't commit suicide because I believed it was the ultimate sin."

But Vanessa's mental meltdown had as much to do with genes as it did with personal crises. "Bipolar disorder is a hereditary brain disease," explains Brian Kennedy, M.D., a psychiatrist in Smyrna, Georgia, who has treated her. "It's caused by a chemical imbalance, and that imbalance in brain chemistry often runs in families."

Like many people coping with mental illness for the first time, Vanessa thought that her symptoms were temporary and that she could "snap out of it" to reclaim her old life. She did manage to pull herself together for a while, graduating with a bachelor's degree in business administration and getting a job with an aerospace and defense contractor. In less than two years, she was promoted to senior financial analyst and was working on a master's degree in business administration at the company's expense. But the stress of her job and studies took a toll on her already precarious mental health. By 1988, seven years after her debilitating college depression, she was showing symptoms of the manic side of her disorder.

"I was becoming depressed, not sleeping, so I started partying a lot in order to chill out from the responsibility of the job," she says. "My personality changed from conservative to very outgoing and flirtatious. At times I was sexually aggressive."

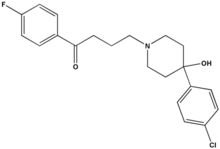

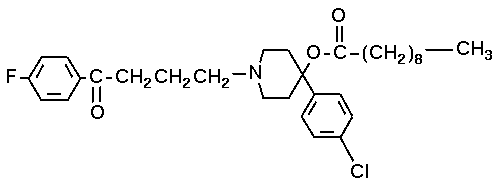

Vanessa's family became aware of her troubled state of mind when she "exploded" in her parents' living room that winter day. She was taken to a private hospital and placed under psychiatric observation for a stay that lasted more than two weeks. By then doctors had diagnosed her bipolar disorder, and they prescribed lithium for her mood swings and Haldol to keep her calm.

She appeared to improve, but her parents and siblings were badly shaken. "It was hard for the entire family," Vanessa's mother, Evelyn Ewell, says of that difficult period. "If I could have taken the sickness instead, I would have." Vanessa's father, Wilmon Ewell, initially thought his daughter's strange behavior was due to drug use. He was stunned when he learned the real reason. "I felt so helpless," he says. "I couldn't get rid of the feelings of frustration."

Vanessa's older brother, Ronney, says that watching his beloved sister's delusions brought him to tears. "I felt a little guilty," he admits. "I thought that maybe if I'd been more attentive when she was growing up, she wouldn't have gotten sick." Because her parents and brother were so upset, Valerie Williamson had to shoulder much of the responsibility for taking care of her sister. At times she felt burdened: "My dad would say, 'I can't get stressed because of my high blood pressure.' My mom would just cry. Then they'd ask me to go see about Vanessa."

Not surprisingly, Vanessa's condition eventually put a strain on her relationship with Valerie. "I think my sister was overwhelmed by my behavior," Vanessa says. "She believed I didn't take responsibility for controlling it."

Though Vanessa saw the toll her illness was taking on her loved ones, she felt powerless to control her behavior. "I think my mother felt ashamed to have a mentally ill child," she reflects.

Facing Up to the Illness

Vanessa was better by the time she left the hospital that first time. She continued to take her medications and resumed her normal schedule even though her mother thought she was returning to work too soon.

She fell in love again and in 1989 was excited to learn that she was pregnant. But her happiness was short-lived. The psychiatrist she was seeing at the time didn't think she was stable enough to go through a pregnancy or rear a child, so she had an abortion. Traumatized, she threw herself into her studies to keep her mind occupied. As her life began to return to normal, she decided to stop taking her medication, in part because she thought the drugs made it difficult for her to concentrate on her thesis.

But without the medication, the disease began to take control of her again. Unable to sleep for days at a time, she would telephone her mother and rant about the past, obsessively recounting the ways in which everyone had wronged her. "It hurt so bad," Evelyn recalls. "She would say the meanest things to me."

On one occasion, Vanessa took off on a journey, imagining that the car she was driving was a jet. Later, miles away from home, she tried to give the car away to a perfect stranger. During one of her worst episodes, she found herself on a psych ward where an attendant tried to rape her. Fortunately she was clearheaded enough to fight him off.

Vanessa now admits that even after ten hospitalizations she never really accepted the fact that she had a disease. It wasn't until after she got her M.B.A., married and became pregnant again that she realized it was time to confront the illness that was derailing her life and keeping her family hostage.

With her doctor's permission and supervision, Vanessa stopped taking her medication during her pregnancy because she was concerned about its effect on her child. And when her marriage began to unravel, she decided to leave her husband and live with her father, knowing that a stress-free environment was best.

After Malcolm was born, Vanessa resumed taking her medication and has been doing so faithfully ever since.

The Turning Point

On the road to healing, Vanessa knew she would have to deal with all the acting out she had done during her manic periods. But she needed a guide. "I had an absolute turning point, when I met Dr. Kennedy," Vanessa says. "He helped me understand that I could live with this illness and take care of my child."

In addition to seeing Kennedy, Vanessa saw Lee-Ferguson, the Atlanta psychotherapist, for two years. "When I first met Vanessa, she was very depressed about the loss of her old life," she says. "Together we came up with a new arena for her to be successful in, as an advocate for the mentally ill. Now she's fully functioning."

Vanessa wrote about her experiences in Journey From Madness to Serenity: A Memoir--Finding Peace in a Manic-Depressive Storm (1stBooks). Through the book and her speaking engagements, she conveys the message that people with mental illnesss can lead rich, satisfying lives.

Her family has begun to treat her not as a sick woman but as the daughter and sister they love and respect. "Sometimes I still see some extreme moods in Vanessa," Ronney says, "but she's a lot calmer." And her father considers her a housemate, not someone he needs to watch over. "She doesn't need a caretaker," he says.

Vanessa has managed to contain an illness that has decimated many lives. She's a member of the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill, a support and advocacy group. Hard at work on a novel, she has even begun dating again.

But above all, Vanessa Sawyer is a mother. "My son and I are really close," she says. Pausing for a moment, she reflects on how far she has come. "When I was sick, I didn't know what I was going to do from one minute to the next," she says. "I'm grateful that my family was there for me."

Getting Help

If you or a relative shows signs of mental illness, these resources can help:

Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance (800) 826-3632 or dbsalliance.org

National Alliance for the Mentally Ill (800) 950-NAMI or nami.org

National Institute of Mental Health (866) 615-NIMH (toll-free), (301) 443-4513, or nimh.nih.gov

National Mental Health Association (800) 969-NMHA or nmha.org

* An Unquiet Mind: A Memoir of Moods and Madness (Knopf) by Kay Redfield Jamison

* Bipolar Disorder: A Guide for Patients and Families (Johns Hopkins University Press) by Francis Mark Mondimore, M.D.

* Handbook of Mental Health and Mental Disorder Among Black Americans (Greenwood Publishing Group) by Dorothy Ruiz

* Surviving Manic Depression: A Manual on Bipolar Disorder for Patients, Families and Providers (Basic Books) by E. Fuller Torrey, M.D., and Michael B. Knable, D.O.

Bebe Moore Campbell's children's book Sometimes My Mommy Gets Angry, about a girl coping with a mentally ill mother, will be published by G.P. Putnam's Sons in September.

ESSENCE contributing writer BEBE MOORE CAMPBELL talks to Vanessa Sawyer--a sister who is successfully managing her 15-year battle with manic-depressive disorder--and her family in "Back From the Edge" (page 144). "I hope that ESSENCE readers will be inspired by this family's struggle and their candor," Campbell says. "Mental illness has to come out of the closet, and it must be destigmatized."

COPYRIGHT 2003 Essence Communications, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2003 Gale Group