Inhalation anesthesia first with halothane followed by enflurane relieved a patient with status asthmaticus who was refractory to conventional therapy including mechanical ventilation. After 13 days of anesthesia while on mechanical ventilation and employing nondepolarizing muscle relaxants, significant neuromuscular impairment, manifested by tetraplegia and sensory disturbance, developed. Anesthesia was discontinued on day 14, and the patient was weaned from mechanical ventilation on day 16. Over the next two months, the neuromuscular impairment markedly improved. Halothane was associated with cardiac arrhythmias and hepatitis necessitating replacement by enflurane. Enflurane appeared to be as effective a treatment for refractory asthma as halothane. The most probable cause of the neuromuscular impairment in our patient was the long-term use of inhalation anesthetics or nondepolarizing muscle relaxants.

Inhalation anesthetics have been used as bronchodilators when status asthmaticus is refractory to conventional therapy including mechanical ventilation.[1] Many reports have been published on successful treatments over short periods of time.[1-3] We now describe a patient with a severe asthma attack who required inhalation anesthesia and had neuromuscular paralysis for 13 days. After cessation of anesthesia, neuromuscular impairment was identified.

Case Report

A 36-year-old, nonsmoking woman with a ten-year history of bronchial asthma was transferred to the emergency room because of a worsening asthma attack. On examination, her pulse rate was 128 beats per minute and blood pressure was 132/100 mm Hg without pulsus paradoxus. Cyanosis was not present, but she was using her accessory muscles of respiration. Her chest was hyperinflated, with poor air entry and generalized wheezing. Arterial blood gas (ABG) values on room air showed a pH of 7.32; [PaCO.sub.2], 53 mm Hg; [Po.sub.2], 70 mm Hg; and [HCO.sub.3], 27.4 mEq/L.

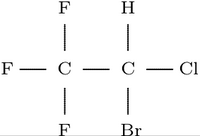

Despite initial treatment with intravenously administered aminophylline (1,000 mg/24 h), methylprednisolone (500 mg in bolus and 40 mg q 4 h), and subcutaneously administered epinephrine (0.3 ml q 0.5 h), her condition failed to improve. On day 2 of admission, her ABG on 5 L of oxygen showed a pH of 7.24;[Pco.sub.2], 67 mm Hg; [Po.sub.2], 62 mm Hg; [HCO.sub.3]-, 29.2 mEq/L. The widened P(A-a)[O.sub.2] difference and progressive respiratory fatigue led us to perform an intratracheal intubation, paralysis (with pancuronium and vecuronium), and volume-cycled ventilation with infusion of isoproterenol. Pancuronium (2 mg/h) was switched to vecuronium after 16 hours due to tachycardia. Vecuronium was administered by intermittent bolus injection (0.5 mg/h). After 16 hours of therapy with no improvement in peak pressures, the decision was made to administer 2 percent halothane by inhalation. The patient had no previous exposure to halothane. Infusion of isoproterenol was discontinued.

After three hours of anesthesia with no improvement, infusion of isoproterenol (1.6 [mu]g/min) was started again. Bronchodilation occurred, as reflected in decreased peak pressures, decreased wheezing, and improvement of ABG estimation. Two attempts were made to lower the concentration of halothane but were averted by increasing peak pressures and reappearance of wheezing. Multifocal ventricular premature beats and trigeminy appeared on day 6 of admission and hepatocellular injury appeared on the next day. We changed the anesthetic from halothane to enflurane because halothane hepatitis was suspected, and uncontrollable arrhythmias developed. The arrhythmias were unresponsive to lidocaine (1 to 3 mg/min) add verapamil (5 to 10 mg/hr) infusion, even though isoproterenol was changed to terbutaline (2.7 [mu]g/min). After switching to enflurane, no wheezing or increased peak pressures occurred, and antiarrhythmic agents could be discontinued. The serum aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase estimations continued to increase up to 480 U/L and 665 U/L (normal less than 35 U/L), and then gradually decreased. A tracheostomy was performed on day 10 with no complications.

On day 14 of admission, inhalational anesthesia was discontinued. After the cessation of anesthesia, flaccid paralysis of the upper and lower extremities was noted, although she could breathe spontaneously The patient was weaned from mechanical ventilation on day 16. Systemic perfusion was adequate at all times. Deep tendon reflexes of all four limbs were absent, and a sensory disturbance of glove and stocking type was recognized. The serum creatine kinase activity rose to 2,470 U/L normal less than 116 UIL) on day 10 and following a transient decline, peaked to 7,930 U/L on day 25. The serum potassium level was 4.1 mEq/L. A head CT scan was normal. Electroencephalography also was normal. An electromyogram showed electric silence and delayed nerve conduction. A muscle biopsy of the right biceps muscle performed on day 19 following admission showed necrosis and regeneration without infiltration of inflammatory cells. The tetraplegia together with the sensory disturbance improved. The results of the EMG and the serum creatine kinase activity also gradually improved. After two months, she was able to walk and her sensory disturbance was remarkably improved. The follow-up muscle biopsy then showed less necrosis and more regeneration.

Discussion

Halothane has been used as a potent bronchodilator for status asthmaticus refractory to conventional therapy.[1-3] Proposed mechanisms for this bronchodilation include direct effect on bronchial smooth muscle, interaction with [beta]-adrenergic receptors, and depression of airway reflexes. We relieved the potentially fatal bronchoconstriction in this patient with inhalation of halothane and infusion of isoproterenol. Halothane, however, induced hepatocellular injury and arrhythmias in one week, almost the same period as reported in the literature.[4] Enflurane, which was administered after halothane, was also an effective bronchodilator, and had less propensity to induce arrhythmias and hepatocellular injury. In animal models of asthma, enflurane has almost the same effect as halothane on bronchodilation.[3] On the other hand, Echeverria et al[2] reported a patient with status asthmaticus who failed to respond to enflurane but responded to halothane. We propose that enflurane should be administered as the first inhalation anesthetic for refractory status asthmaticus, and if this fails, then halothane should be considered. Isoflurane is also a potent agent for status asthmaticus, but it was not available in Japan.

In our case, tetraplegia and sensory disturbance developed. The EMG showed neurogenic changes, while at the same time, the muscle biopsy showed myogenic alterations. As to the causes, disuse atrophy and acute corticosteroid myopathy are excluded since neither induces massive rhabdomyolysis and sensory disturbances. Nondepolarizing muscle relaxants and inhalation anesthetics induce myogenic changes, though neither induces sensory disturbances.[5,6] The improvement of both tetraplegia and sensory disturbance after the cessation of both drugs suggests the tetraplegia and sensory disturbance arose from the same cause. Whether nondepolarizing muscle relaxants or inhalation anesthetics or both are the cause of the neuromuscular disorder remains uncertain.

References

[1] Ueda Y, Fujimura M, Aoyama N, Doi Y, Hiraki N. Intractable status asthmaticus treated by prolonged halothane and enflurane inhalation. ICU To CCU 1987; 11:685-90 [2] Echeverria M, Gelb AW, Wexler HR, Ahmand D, Kenefick P. Enflurane and halothane in status asthmaticus. Chest 1986; 89:152-54 [3] Hirshman CA, Bergman NA. Halothane and enflurane protect against bronchospasm in an asthma dog model. Anesth Analg 1978; 57:629-33 [4] Kon H, Namiki A, Kashiki K. Change of liver function in a patient with bronchial asthma undergoing long-term halothane inhalation therapy. Masui To Sosei 1985; 21:231-34 [5]Op de Coul AAW, Lambregts PCLA, Koeman J, Van Puyenbroek MJE, Ter Laak HJ, Gabeels-Festen AAWM. Neuromuscular complications in patients given Pavulon (pancuronium bromide) during artificial ventilation. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 1985; 87:17-22 [6] Rubiano R, Chang J-L, Carroll J, Sonbolian N, Larson CE. Acute rhabdomyolysis following halothane anesthesia without succinylcholine. Anesthesiology 1987; 67:856-57

COPYRIGHT 1990 American College of Chest Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group