Family physicians see many patients who present with abdominal symptoms. The differential diagnosis is often long and includes conditions that are minor nuisances as well as life-threatening diseases. Several studies have suggested that products containing sorbitol may be the cause of abdominal complaints in some patients.[1-4] Screening for sorbitol intolerance can be done quickly and can save the patient discomfort and the expense of routine laboratory tests.

Case Report

A young white male patient with a closed head injury, which resulted in a persistent vegetative state and subsequent seizure disorder, was treated with 4 g of liquid valproic acid (Depakene) daily by gastric tube. He developed chronic diarrhea for which repeated laboratory tests were done over a 6-month period, including stool studies for ova and parasites, enteric pathogens, Clostridium difficile toxin, and fecal osmolarity; an upper gastrointestinal series; and a gastric tube dye study. Blood studies included amylase, lipase, sedimentation rate, zinc, gastrin, vasoactive intestinal polypeptide, calcitonin, and antinuclear antibodies; urine serotonin was also checked. All of the results of these tests were normal with the exception of several stool studies positive for C difficile. The diarrhea persisted despite multiple enteral nutrition formulas, trials of Imodium and Lactinex granules, three treatments with oral vancomycin (for the positive C difficile studies), and a course of intravenously administered antibiotics.

After a 75-pound weight loss, a Hickman catheter was placed and parenteral nutrition was initiated. The diarrhea persisted, and after two bouts of central line sepsis, 3 months of parenteral nutrition, and an additional hospitalization, it was discovered that the valproic acid elixir contained sorbitol. Valproic acid sprinkles were substituted, and within 36 hours, the diarrhea resolved.

Discussion

Sorbitol is present in a wide range of prescription and over-the-counter products. Historically, it has been used to induce catharsis, but currently it is also being used as a sweetener and for its humidifying and antihardening properties. The presence of sorbitol is commonly overlooked by physicians, however, despite multiple studies and case reports that have shown it to be a cause of abdominal symptoms.[1-8] The Physicians' Desk Reference,[9] which is widely used as a source of drug information, does not always list sorbitol as an active or inactive ingredient when present, and when sorbitol is fisted, the concentration is not always specified.

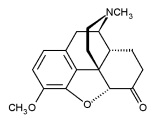

Sorbitol is found naturally in a variety of fruits and plants, and is used commercially in a wide range of products. It is a popular sugar substitute in dietetic foods, especially sugar-free chewing gum and mints. Sorbitol is present in over-the-counter medications such as liquid acetaminophen, vitamins, and cough preparations. Prescription elixirs also frequently contain sorbitol. Examples include theophyline, cimetidine, codeine, isoniazid, lithium, and valproic acid.

Sorbitol is a polyalcohol sugar that is poorly absorbed by the small intestine. The incompletely absorbed carbohydrate passes into the colon where it has an osmotic effect that can lead to diarrhea. It also serves as a substrate for bacterial fermentation and hydrogen production, which can result in abdominal bloating and gas. A portion of the hydrogen produced is absorbed and subsequently excreted through the lungs. The measurement of breath hydrogen by gas chromatography has been found to be a sensitive technique for detecting carbohydrate malabsorption.[1]

Despite marked intersubject variability, there is a dose-related intolerance to sorbitol.[1] Biochemical intolerance has been defined as an increase in breath hydrogen without clinical symptoms, whereas clinical intolerance implies the presence of abdominal symptoms.[2] Hyams[1] has shown that in most individuals, ingestion of 5 g of sorbitol is associated with a significant increase in breath hydrogen, 10 g causes mild gastrointestinal distress such as gas and bloating, and 20 g causes severe symptoms such as cramps and diarrhea.

Jain et al[2] studied 23 whites and 19 nonwhites (Asian Indians and US blacks) aged 25 to 55 years. They excluded volunteers with a history of gastrointestinal disease or use of antibiotics in the past 6 months. After an overnight fast, the subjects were given 10 g of sorbitol, after which breath hydrogen was measured for 4 hours and abdominal symptoms were recorded for 6 hours. Severe clinical intolerance, defined as bloating, abdominal pain, and diarrhea, was present in 32% of nonwhites and 4% of whites. The 10 g of sorbitol ingested would be equivalent to chewing 4 or 5 pieces of sugar-free gum in a short period of time. The significantly higher prevalence in nonwhites has not been explained.

The above studies indicate that sorbitol intolerance is not uncommon. Patients who consume products containing sorbitol are at risk for experiencing sorbitol-induced abdominal symptoms. Diabetics frequently consume large amounts of sugar-free products. A study done by Badiga et al[3] showed that diarrhea is significantly more prevalent in diabetics who consume sorbitol-containing foods compared with diabetics who do not consume these products. Patients for whom medications in elixir form are prescribed, including pediatric, geriatric, and patients with severe chronic disabilities, are also at increased risk.

This case is a dramatic example of the adverse outcomes that can result from the therapy we prescribe. Not only does it highlight the problems of a specific component of many medications, it also serves to remind us to review all medications as a potential cause for an unexpected clinical course.

With the knowledge of products that may contain sorbitol and the types of patients who might use such products, the family physician can efficiently screen patients who present with abdominal complaints. Questioning about sorbitol intake before initiating a laboratory workup could greatly reduce costs. Although the Physicians' Desk Reference may not be a definitive reference in the area, most pharmacists should be able to assist in determining if a product contains sorbitol, as well as suggesting alternative form of the medication available (eg, sprinkles). The amounts of sorbitol in some commonly used medications are listed in Table 1. Perhaps, as more controlled studies demonstrate the prevalence of sorbitol intolerance, the use of sorbitol as an "inactive" ingredient, or its concentration, will be decreased and drug manufacturers will consistently list sorbitol in their product labels.

References

[1.] Hyams JS. Sorbitol intolerance: an unappreciated cause of functional gastrointestinal complaints. Gastroenterology 1983; 84:30-3. [2.] Jain NK, Rosenberg DB, Ulahannan MJ, Glasser MJ, Pitchumoni CS. Sorbitol intolerance in adults. Am J Gastroenterol 1985; 80: 678-81. [3.] Badiga MS, Jain NK, Casanova C, Pitchumoni CS. Diarrhea in diabetics: the role of sorbitol. J Am Coll Nutr 1990; 9:578-82. [4.] Edes TE, Walk BE, Austin JL. Diarrhea in tube-fed patients: feeding formula not necessarily the cause. Am J Med 1990; 88:91-3. [5.] Edes TE, Walk BE. Nosocomial diarrhea: beware the medicinal elixir. South Med J 1989; 82:1497-1500. [6.] Veerman MW. Excipients in valproic acid syrup may cause diarrhea: a case report. DICP 1990; 24:832-3. [7.] Chusid MJ, Chusid JA. Diarrhea induced by sorbitol [letter]. J Pediatr 1981; 99:326. [8.] Goldberg LD, Ditchek NT. Chewing gum diarrhea. Am J Dig Dis 1978; 23:568. [9.] Physicians' Desk Reference. 45th ed. Oradell, NJ: Medical Economics Data, 1991.

COPYRIGHT 1993 Dowden Health Media, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group