INTRODUCTION: Hereditary angioedema (HAE) is an infrequent disorder characterized by abnormal serum levels and/or function of complement Clq esterase inhibitor (Clq INH). Clinically it presents with recurrent attacks of subcutaneous and/or submucosal swelling. When the gastrointestinal (GI) tract is involved, an exacerbation of HAE results in numeorus GI symptoms but rarely acute pancreatitis.

CASE PRESENTATION: A 40-year old man presented to our institution with a 1-month history of increasing anxiety and a 1-day history of intermittent abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. He described the pain as severe with radiation through to his back. He denied melena, hematochezia or previous gallbladder disease. He had a past medical history of peptic ulcer disease, generalized anxiety disorder and Clq esterase inhibitor deficiency, diagnosed at the age of two. His HAE attacks, occurring 5 to 6 times per year, generally lasted 1 to 2 days and were characterized by recurrent episodes of painless, nonpruritic swelling of the skin, abdominal pain and nausea. His medications included esomeprazole, sertraline, danazol and ondansetron, dyphenhydamine and hydromorphone as needed for angioedema flares. He was a nonsmoker and denied use of alcohol. On admission to the ICU, he was afebrile (98[degrees]F), hemodynamically stable with minimal sinus tachycardia and tachypnea. His exam was remarkable for epigastric tenderness but no hepatospleuomegaly or palpable abdominal masses. Laboratory studies revealed a white blood cell count of 19,300/cu mm, a hematocrit of 55 %, a serum amylase of 1,176 IU/L, a serum lipase of 11,485 IU/L, a serum aspartate and alanine aminotransferase of 68 IU/L and 105 IU/L respectively and a serum alkaline phosphatase of 138 IU/L. Other laboratory values, including serum total bilirubin, electrolytes, creatinine and triglycerides were normal. The Clq esterase inhibitor antigen was low at 7 mg/dl (normal, 19-37 mg/dl). With aggressive intravenous hydration, antibiotic prophylaxis, gastric decompression, pain control, and continuation of his home medications including esomeprazole and danazol, the patient improved and his pancreatic enzymes began to normalize within 72 hours. Abdominal ultrasonography revealed no biliary obstruction or gallbladder pathology. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen confirmed acute pancreatitis with patchy areas of pancreatic necrosis, mild bowel swelling and no intra or extrahepatic bile duct dilatation (Figure). Before discharge he underwent upper GI endoscopy, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and analysis of bile for microlithiasis. These failed to explain the cause of pancreatitis thus favoring HAE as the most probable etiology.

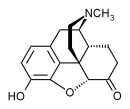

[FIGURE OMITTED]

DISCUSSIONS: HAE affects between 1/10000-1/50000 people worldwide and can present after stressful triggering events, such as severe anxiety as seen in our patient. Besides subcutaneous swellings and occasionally fatal upper airway edema, it can also cause severe GI symptoms. However, a thorough literature search revealed only one case report describing HAE associated with pancreatitis. A high degree of clinical suspicion for possible pancreatitis should be maintained when facing a patient with history of HAE and abdominal pain. One quarter of HAE cases represent a new gene mutation so when no obvious cause for pancreatitis is found and recurrent episodes of pancreatitis occur then HAE should be considered in the differential diagnosis. Finally, treatment options are limited since in the United States Clq INH concentrate use has not been approved. Moreover, treatment with fresh frozen plasma (FFP) should be undertaken with caution since a number of cases have been reported with worsening of angioedema symptoms.

CONCLUSION: HAE, although rarely recognized and likely under-reported can cause pancreatitis via either swelling of the pancreas per se or by causing edema interfering with normal pancreatic drainage. Current treatment options for acute angioedema are limited with observation being the most common form of treatment since most attacks are self limited and of short duration.

DISCLOSURE: Evans Fernandez, None.

Evans R. Fernandez MD * Damir Matesic MD Nicholas E. Vlahakis MD Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN

COPYRIGHT 2005 American College of Chest Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2005 Gale Group