Overview

Hydromorphone is a drug used to relieve moderate to severe pain. Hydromorphone is known by the trade names Dilaudid® and Palladone®. It belongs to a category of drugs known as opioid agonists. It is commonly given to patients who have recently undergone surgery or who have suffered serious injury, and it is given intravenously, intramuscularly, rectally, or orally. Hydromorphone is often sought after by opiate drug abusers as it is one of the most potent of all prescription narcotics.

Details

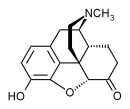

Hydromorphone, a semi-synthetic μ-opioid agonist, is a hydrogenated ketone of morphine and shares the pharmacologic properties typical of opioid analgesics. Hydromorphone and related opioids produce their major effects on the central nervous system and gastrointestinal tract. These include analgesia, drowsiness, mental clouding, changes in mood, euphoria or dysphoria, respiratory depression, cough suppression, decreased gastrointestinal motility, nausea, vomiting, increased cerebrospinal fluid pressure, increased biliary pressure, pinpoint constriction of the pupils, increased parasympathetic activity and transient hyperglycemia. When injected, particularily intravenously, hydromorphone produces more intense contraction sensation in the muscles and a more powerful 'rush' than other opioids, even more so than heroin (diacetylmorphine).

CNS depressants, such as other opioids, anesthetics, sedatives, hypnotics, barbiturates, phenothiazines, chloral hydrate and glutethimide may enhance the depressant effects of hydromorphone. MAO inhibitors (including procarbazine), first-generation antihistamines (brompheniramine, promethazine, diphenhydramine, chlorpheniramine), beta-blockers and alcohol may also enhance the depressant effect of hydromorphone. When combined therapy is contemplated, the dose of one or both agents should be reduced.

Side Effects

Adverse effects of hydromorphone are similar to those of other opioid analgesics, and represent an extension of pharmacological effects of the drug class. The major hazards of hydromorphone include respiratory and CNS depression. To a lesser degree, circulatory depression, respiratory arrest, shock and cardiac arrest have occurred. The most frequently observed adverse effects are sedation, nausea, vomiting, constipation, lightheadedness, dizziness and sweating.

Read more at Wikipedia.org