Abstract

Despite the development of sophisticated diagnostic procedures and treatments for other otologic and neurotologic conditions, tinnitus remains difficult to manage. Several investigators have shown that lidocaine has an effect on temporarily (for several minutes) relieving subjective tinnitus, but few reports have described the response to lidocaine according to different individual patient characteristics. Over a 24-year period, we administered either 60 or 100 mg of intravenous lidocaine to 117 ears in 103 patients with subjective tinnitus (14 patients received treatment bilaterally). Within 5 minutes of treatment, 83 ears (70.9%) experienced either complete or partial relief The 100-mg dose was more effective than the 60-mg dose in completely eliminating tinnitus (34.9 vs 20.6%), but the two doses were comparable when elimination rates were combined with rates of reduction of tinnitus (71.1 and 70.6%, respectively). With respect to individual patient characteristics, ears with low- to middle-tone tinnitus had a better response, as did ears in which the hearing level was 40 dB or higher and ears of patients aged 60 years and older. The response to lidocaine was not correlated with the baseline loudness of tinnitus or to its duration.

Introduction

Despite the development of sophisticated diagnostic procedures and treatments for other otologic diseases, tinnitus remains difficult to manage. The suppressive effect of local anesthetics on tinnitus was discovered serendipitously by Barany in 1935. (1) He reported that tinnitus stopped when procaine was administered into the inferior turbinate as a local anesthetic during intranasal surgery. This clinical observation prompted Lewy to perform the first study of the use of local anesthetics for relief of tinnitus. (2) He intravenously administered procaine, dibucaine, and quinine combined with urethan. Gejrot in 1963 (3) and 1976 (4) and Englesson et al (5) in 1976 reported beneficial effects of IV lidocaine on tinnitus in patients with Meniere's disease and other conditions. Also in 1976, Sakata and Umeda reported that tinnitus diminished in 48 of 58 patients (82.8%) after transtympanic injection of lidocaine. (6) Shea and Harell found that tinnitus was relieved in 43 of 54 patients (79.6%) following 1V injection of lidocaine. (7) Israel et al proved the lidocaine effect in a placebo-controlled, double-blind, crossover study. (8) Suzuki reported that lidocaine influenced the auditory-evoked brainstem response and action potentials in guinea pigs. (9)

While investigators have shown that lidocaine has an effect on subjective tinnitus, few have described the response according to different individual patient characteristics. In this article, we describe the response to IV lidocaine according to various individual parameters.

Patients and methods

Between 1977 and 2001, we administered IV lidocaine to 117 ears in 103 patients with subjective tinnitus at the Pulec Ear Clinic in Los Angeles; 14 patients were treated bilaterally. This group included patients aged 23 to 83 years (mean: 55). All patients provided a thorough history, including information on the duration, location, severity, and nature of the tinnitus as well as information on smoking, caffeine intake, head injury, noise exposure, serious illness, and ototoxic drug exposure. The physical and neurotologic examinations included audiometry for pure tones and speech discrimination, early latency brainstem audiometry, electronystagmography, and petrous pyramid x-rays. Magnetic resonance imaging was performed on patients who were suspected of having an acoustic neuroma. Blood tests included measurements of the complete blood count, electrolyte levels, thyroid and liver function, fluorescent treponemal antibody levels, lipoprotein phenotypes, and 5-hour glucose tolerance. (10,11) Audiometric evaluation was also performed to determine the loudness and pitch of tinnitus. The causes of tinnitus were varied (table 1).

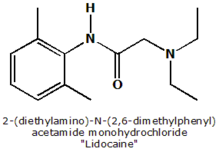

With the patient in a sitting position, either 60 or 100 mg (3 or 5 ml) of 2% lidocaine was injected intravenously. The smaller dose was administered to those ears that were treated between 1977 and 1984 (n = 34) and the larger dose to those that were treated thereafter (n = 83). We asked each patient to evaluate any perceived alteration in tinnitus during the first 5 minutes after injection, including an estimate of the percentage of reduction in those patients who reported a reduction. Post-treatment tinnitus status was classified as either absent, reduced, no change, or worse. An estimated reduction of less than 20% was considered to represent no change.

Results

Overall response. Following treatment of the group as a whole, tinnitus was absent in 36 ears (30.8%), reduced in 47 ears (40.2%), unchanged in 26 ears (22.2%), and worse in 8 ears (6.8%) (figure 1). Lidocaine was either completely or partially effective in 83 ears (70.9%). Although IV lidocaine provides only temporary (for several minutes) relief in most cases, two of our patients experienced lasting (for several months) relief.

Response and etiology. We calculated the rate of response in ears with the four most common etiologies (table 2). The best response was seen in those with presbycusis (84.2%) and the worst in those with acoustic trauma (55.6%).

Response and dose. The 100rag dose of lidocaine was more effective than the 60-mg dose in eliminating tinnitus (figure 2). Among the 83 ears that received the larger dose, tinnitus was absent in 29 ears (34.9%) and reduced in 30 (36.1%). Among the 34 ears that received the smaller dose, tinnitus was absent in 7 ears (20.6%) and reduced in 17 (50.0%). When absence and reduction are combined, the improvement rates were similar--71.1% (59/83) with the larger dose and 70.6% (24/34) with the smaller dose.

Response and pitch. Sixty of the 117 ears were tested to assess the pitch of tinnitus. Ears in which the pitch was less than 4,000 Hz (low- to middle-tone tinnitus) had a better response than did those with a higher pitch (figure 3). In the former group, tinnitus was eliminated in 8 of 21 ears (38.1%) and reduced in 10 others (47.6%)--an overall improvement rate of 85.7% (18/21). In the latter group (high-frequency tinnitus), tinnitus was eliminated in 9 of 39 ears (23.1%) and reduced in 16 others (41.0%)--an overall improvement rate of 64.1% (25/39).

Response and hearing level Hearing level was assessed in 116 of the 117 ears. Ears with a hearing level of 40 dB or more had a significantly better response (p = 0.0067) than did those with a lower level (figure 4). Heating level was less than 40 dB in 85 ears; tinnitus was eliminated in 26 (30.6%) and reduced in 29 (34.1%)--an overall improvement rate of 64.7% (55/85). Among the 31 ears in which the hearing level was more than 40 dB, tinnitus was eliminated in 10 (32.3%) and reduced in 18 (58.1%)--an overall improvement rate of 90.3% (28/31).

Response and age. Response was significantly better (p = 0.026) in patients who were 60 years or older (figure 5). In patients who were younger than 60 years, tinnitus was eliminated in 18 of 71 ears (25.4%) and reduced in 27 (38.0%)--an overall improvement rate of 63.4% (45/71). Among the patients who were 60 years or older, tinnitus was eliminated in 18 0f46 ears (39.1%) and reduced in 20 (43.5%)--an overall improvement rate of 82.6% (38/46).

Other parameters. We also analyzed responses according to the degree of pretreatment loudness of tinnitus and the duration of the tinnitus and found no correlation.

Discussion

The finding that local anesthetics, particularly lidocaine, can relieve tinnitus supports the hypothesis that tinnitus might be caused by neural hyperactivity. It is known that increased sodium conductance increases the sensitivity of axons and in many cases makes the mechanoreceptors sensitive. Lidocaine is a sodium channel blocker, and decreased sodium conduction affects neurons that have high discharge rates. Several authors (3-9) have reported that lidocaine was effective in relieving tinnitus in 60 to 80% of patients, and our results were compatible with these findings.

In our series, 100 mg of IV lidocaine was more effective than 60 mg. Perucca and Jackson reported that a lidocaine plasma concentration of at least 1.0 [micro]g/ml is necessary to reduce tinnitus. (12) However, higher levels are associated with more pronounced side effects. We observed no case of significant side effects with either the 60- or 100-mg dose.

Our study showed that lidocaine was more effective in alleviating low- to middle-tone tinnitus than high-tone tinnitus. Several other studies yielded similar results. (13,14) Shea reported that IV lidocaine blocks 10% of the transmission of neural hyperactivity through each synapse, and thus it has more effect on the slow pathway (low-frequency tinnitus) than on the rapid pathway (high-frequency tinnitus). (13)

In recent years, increased efforts have been made to find a more easily administered pharmaceutical treatment for tinnitus that is as effective as IV lidocaine; administration of lidocaine is not a routine treatment option because of its inconvenience. Several investigators have shown that the response to lidocaine can predict the response to carbamazepine and serotonin, and therefore these other agents can be used in the selection of suitable candidates for treatment. (7,15,16)

References

(1.) Barany R. Die Beeinflussung des Ohrensausens durch iv Injizierte Lokalanaesthetica. Acta Otolaryngol 1935:23:201-3.

(2.) Lewy RB, Treatment of tinnitus aurium by the iv use of local anesthetic agents. Arch Otolaryngol 1937;25:178-83.

(3.) Gejrot T. Intravenous Xylocaine in the treatment of attacks of Meniere's disease. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl 1963; 188:190-5.

(4.) Gejrot T. Intravenous Xylocaine in the treatment of attacks of Meniere's disease. Acta Otolaryngol 1976;82:301-2.

(5.) Englesson S, Larsson B, Lindquist NG, et al. Accumulation of 14C-lidocaine in the inner ear. Preliminary clinical experience utilizing intravenous lidocaine in the treatment of severe tinnitus. Acta Otolaryngol 1976;82:297-300.

(6.) Sakata E, Umeda Y. Treatment of tinnitus by transtympanic infusion of lidoeaine. Auris Nasus Larynx 1976;3:133-8.

(7.) Shea J, Harell M. Management of tinnitus aurium with lidocaine and carbamazepine. Laryngoscope 1978;88:1477-84.

(8.) Israel JM, Connelly JS, McTigue ST, et al. Lidocaine in the treatment of tinnitus aurium. A double-blind study. Arch Otolaryngol 1982;108:471-3.

(9.) Suzuki M. The effect of intravenous injection of lidocaine on the auditory system. Auris Nasus Larynx 1983;10:25-36.

(10.) Pulec JL Pulec MB, Mendoza I. Progressive sensorineural hearing loss, subjective tinnitus and. vertigo caused by elevated blood lipids. Ear Nose Throat J 1997;76:716-20.

(11.) Pulec JL. Treatment of tinnitus. ORL and Allergy Digest 1979;41:15-26.

(12.) Perucca E, Jackson P. A controlled study of the suppression of tinnims by lidocaine infusion (relationship of therapeutic effect with serum lidocaine levels). J Laryngol Otol 1985;99:657-61.

(13.) Shea JJ. Medical treatment of tinnitus. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Belg 1985;39:613-19.

(14.) Ueda S. [Treatment of tinnitus with intravenous lidocaine]. Nippon Jibiinkoka Gakkai Kaiho 1992;95:1389-97.

(15.) Simpson JJ, Davies WE. A review of evidence in support of a role for 5-HT in the perception of tinnitus. Hear Res 2000;145:1-7.

(16.) Sanchez TG, Balbani AP, Bittar RS, et al. Lidocaine test in patients with tinnitus: Rationale of accomplishment and relation to the treatment with carbamazepine. Auris Nasus Larynx 1999;26: 411-17.

From the Department of Otolaryngology, Tokyo Medical University (Dr. Otsuka and Dr. Suzuki), and the Pulec Ear Clinic, Los Angeles (Dr. Pulec).

Reprint requests: Koji Otsuka, MD, Department of Otolaryngology, Tokyo Medical University, 6-7-1 Nishi-shinjuku Shinjuku ku, Tokyo, Japan 160-0023. Phone: 81-3-3342-6111; fax: 81-3-3346-9275; e-mail: otsukaent@aol.com

COPYRIGHT 2003 Medquest Communications, LLC

COPYRIGHT 2003 Gale Group