Hypertension affects 58 million Americans. Dentists frequently encounter patients who are using one or more antihypertensive medications. This study evaluates the incidence of active duty soldiers dispensed antihypertensive medications at a large military installation. Lisinopril was the most frequently prescribed antihypertensive medication during a 2-month period in 1997 and was followed by hydrochlorothiazide, amlodipine, propranolol, felodipine, verapamil, atenolol, diltiazem, terazosin, clonidine, nifedipine, and metoprolol. These 12 drugs accounted for 93.46% of all antihypertensive medications dispensed. In this study, the percentage of active duty soldiers dispensed any antihypertensive medication was 1.51% (30 different medications were dispensed); 0.16% of all soldiers younger than age 30 and 1.25% of all soldiers older than age 30 were prescribed 1 of the 12 most commonly prescribed antihypertensive agents. Considering the same top-12 antihypertensive agents, the percentage of male soldiers younger than 30 who received a prescription was 0.24% and the percentage of male soldiers older than 30 who received a prescription was 4.3%. The percentage for males older than 40 receiving 1 of the 12 medications listed above was 12.05%. Similarly, the percentages for females were 0.27% for younger than 30, 1.87% for older than 30, and 3.51% for older than 40. Active duty males older than age 30 were more than twice as likely to be prescribed an antihypertensive agent than females in the same age group. Male active duty soldiers older than age 40 were more than 50 times more likely to be prescribed an antihypertensive agent than active duty males younger than 30.

Introduction

Dentists frequently encounter patients who use one or more antihypertensive medications. Recent surveys have shown that drugs such as lisinopril (Zestril), hydrochlorothiazide (Oretic), nifedipine (Procardia), and furosemide (Lasix) are commonly prescribed on U.S. militarv installations.1 Hypertension accounts for the largest number of outpatient cardiac prescriptions in the United States, yet the disease is adequately controlled in fewer than half of the 58 million Americans who have it.2 Recognition of severe, undiagnosed, or uncontrolled hypertension before the initiation of dental treatment may help avoid a possible cerebrovascular accident or myocardial infarction. Stress associated with dental treatment may "raise a patient's already elevated blood pressure to dangerous levels."3

Use of vasoconstrictors in local anesthetics or retraction cord may also contribute to dangerous increases in blood pressure. All injectable local anesthetics cause some degree of localized vasodilation. Vasoconstrictors are added to local anesthetics to counter vasodilating affects and thus increase the duration of action. Vasoconstrictors used in local anesthetics are "chemically identical or quite similar to the sympathetic nervous system mediators epinephrine and norepinephrine."4 Vasoconstrictor actions that resemble the response of adrenergic nerves to stimulation are called adrenergic drugs. The terms "adrenergic drugs,' "sympathomimetics," and "sympathetic amines" are synonymous. Three naturally occurring sympathetic amines known to act in the sympathetic nervous system are dopamine, norepinephrine, and epinephrine.5 Catecholamines are actually sympathomimetic amines derived from catechol. The catecholamines epinephrine and levonordefrin are vasoconstrictors commonly used in local anesthetic preparations.

Adrenergic receptors are found throughout the body. There are two types, termed alpha (a) and beta (B) based on the inhibitory or excitatory actions of the catecholamines on smooth muscle."4 Activation of a receptors can cause contraction of smooth muscle in blood vessels. There are two types of a receptors: alpha^sub 1^ are excitatory postsynaptic and alpha^sub 2^ are inhibitory postsynaptic. Activation of beta receptors produces smooth muscle relaxation and cardiac stimulation. beta receptors can be beta^sub 1^, which are found in heart and small intestine and are responsible for cardiac stimulation and lipid lysis, or beta^sub 2^, which are found in bronchi. vascular beds, and uteri and are responsible for bronchodilation and vasodilation.4

Dentists often have the opportunity to identify hypertension in otherwise healthy people who may not see a physician on a regular basis.2 Blood pressure should be measured at each patient visit, with the understanding that hypertension cannot be diagnosed based on a single blood pressure measurement.

To determine if a patient has elevated blood pressure, a clinician must know what constitutes normal. This may vary slightly depending on the source. Optimal blood pressure is somewhat less than 120 mm Hg systolic and 80 mm Hg diastolic. The Fifth Report of the Joint National Committee on the Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC V) recommended that "initial elevated readings should be confirmed on at least two subsequent visits over one to several weeks with average levels of diastolic blood pressure of 90 mm Hg or greater and/or systolic pressure 140 mm Hg or greater required for diagnosis." Obviously, systolic levels close to 200 mm Hg and diastolic levels around 120 mm Hg should be referred for immediate treatment.6 Unusually low levels should be evaluated for possible cause. JNC VI classifies normal blood pressure as systolic /= 180 mm Hg over >/= 110 mm Hg.7

Ninety-five percent of all hypertension is of unknown origin (essential hypertension).3 When the cause can be clearly established, the term secondary hypertension is used. Secondary hypertension can be caused by such things as (1) oral contraceptives, (2) kidney disorders (renal failure and glomerulonephritis), and (3) certain adrenal gland problems. Chronic high blood pressure is insidious and can cause damage to the heart, brain, kidneys, and eyes. Untreated, hypertension can cause major illness or even death.8

Once a person is diagnosed with hypertension, treatment is begun with the goal of controlling blood pressure by the most conservative means possible, thus preventing damage to organ systems. Treatment is based on evaluation of a patient's blood pressure and cardiovascular risk factors. According to JNC VI, patients can be divided into the following three risk groups:

[1) Risk group A includes patients with high normal blood pressure or stage 1, 2, or 3 hypertension who do not have cardiovascular disease, target organ damage, or other risk factors. Major risk factors are smoking, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, age > 60 years, sex (men and postmenopausal women), and a family history of cardiovascular disease. Target organ damage includes left ventricular hypertrophy, previous myocardial infarction, and nephropathy. Group A patients with stage 1 hypertension are candidates for prolonged (up to 1 year) lifestyle modification. Group A patients with stage 2 or 3 hypertension warrant drug therapy.

(2) Risk group B includes hypertensive patients with no cardiovascular or target organ disease but with one or more risk factors, not including diabetes mellitus. When multiple risk factors are present, antihypertensive drugs should be considered as initial therapy.

(3) Risk group C includes patients with hypertension who have cardiovascular disease or target organ damage. This group should be considered for prompt pharmacologic therapy.7

Treatment ranges from diet, exercise, and avoidance of tobacco and alcohol to use of various pharmacologic agents. The Joint National Committee proposed a stepped care program in 1980. A similar stepped pharmacologic approach is also listed in the most recent report, JNC VI.7

The decision to initiate pharmacologic treatment is made with consideration of the degree of blood pressure elevation and the presence of target organ damage, cardiovascular disease, or other risk factors, Therapy for most patients begins with the lowest dosage of a selected antihypertensive agent. A diuretic or beta-blocker is recommended as the first drug to be used. Certain angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors are also approved for initial therapy. ACE inhibitors are especially useful for treating hypertension in diabetic patients with proteinuria.7 If blood pressure remains uncontrolled after 1 to 2 months, the next higher dosage level should be prescribed. If response is still inadequate, a second drug from another class is added or an agent from a different class is substituted. If a diuretic was not chosen as the first-line drug, then it should be prescribed. Once hypertension has been effectively controlled for 1 year, every effort should be made to decrease the dosage and number of antihypertensive agents.7 Additional medications used to control hypertension include (1) diuretics, (2) beta-adrenergic blockers, (3) alpha-adrenergic blockers, (4) alphabeta-blockers, (5) central synpatholytics, (6) vasodilators, (7) ACE inhibitors. and (8) calcium channel blockers.

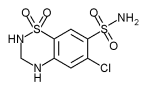

Diuretics have two possible mechanisms of action: (1) the hypotensive effect is a direct or indirect consequence of sodium and chloride depletion, or (2) diuretics act by direct or indirect vascular effects not related to natriuresis. Multiple lines of evidence support the view that salt and extracellular volume depletion is related to the hypotensive effect.9 During the first few weeks of thiazide therapy, there is a 10% to 15% reduction in plasma volume. In the short term, cardiac output decreases, resulting in an increase in peripheral vascular resistance. With chronic administration, blood volume and cardiac output return toward (but do not reach) pretreatment levels. This suggests that long-term pressure reduction is related to a late decline in peripheral resistance. Ingestion of large amounts of sodium can counteract or reverse the hypotensive actions of diuretics,9 The use of diuretics may cause dry mouth or lichenoid reactions. The dentist must also consider orthostatic hypotension and that prolonged use of a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) can reduce the antihypertensive effects.3 NSAID use in conjunction with an antihypertensive medication is common. Estimates suggest that as many as 20 million Americans taking antihypertensive drugs receive NSAID therapy on a short-term or longterm basis.10,11

beta-Adrenergic antagonists (beta-blockers) appeared in the 1960s and are commonly used to treat hypertension. They function by blocking beta-adrenergic receptor sites (beta^sub 1^ or beta^sub 2^) and may have direct effects on the myocardium. beta-Blockers are considered either nonselective or cardioselective. Nonselective beta-blockers interfere with both beta^sub 1^ and beta^sub 2^ receptors; treatment of patients who are taking beta-blockers (such as propranolol) requires careful restriction of vasoconstrictor use (maximum 0.036 mg of epinephrine or 0.20 mg of levonordefrin). Like the diuretics, beta-blockers may also potentiate orthostatic hypotension. Prolonged use of NSAIDs may reduce the antihypertensive effectiveness of beta-blockers. Use of beta-blockers may also reduce hepatic clearance of lidocaine, resulting in increased serum levels.3,12

alphabeta-Blockers such as labetalol (Normodyne) are also occasionally prescribed for hypertension. This drug reduces blood pressure without reflex tachycardia or significant reduction in heart rate through a combination of alpha- and beta-blocking effects. 13 This medication may cause postural effects such as dizziness and may be more effective in black people than other beta-blockers.6

Hydralazine HCI (Apresoline) and minoxidil (Loniten) are direct vasodilators. They work by direct smooth muscle vasodilation, primarily arteriolar. Both drugs cause some tachycardia and increased plasma renin activity. Hydralazine HCl is used in combination with beta-blockers and diuretics to minimize side effects. It has been used extensively during pregnancy. Minoxidil can cause increased hair growth (hypertrichosis) in 80% of patients.2,6

Sympatholytic drugs such as prazosin HCI (Minipress) are also used to treat hypertension. Prazosin HCl is an alpha^sub 1^-adrenergic antagonist that reduces preload and afterload through a relaxing effect on veins and arterioles. alpha^sub 1^-Receptor blockers may also cause postural effects such as dizziness.2,6

ACE inhibitors (lisinopril) block the conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II.14 ACE converts angiotensin I to angiotensin II. Most of the conversion occurs during passage of blood through the lungs. This conversion has effects on the reninangiotensin-aldosterone system that cause increased vasoconstriction and increased sodium and water reabsorption.2 ACE inhibitors can cause angioedema of the lips, face, and tongue and loss of taste. They can also result in neutropenia and thrombocytopenia. Their effectiveness can be reduced by prolonged use of NSAIDs.3

Calcium antagonists (calcium channel blockers) are considered alternative first-line drugs. Calcium antagonists inhibit calcium ion influx into cardiac and vascular smooth muscle.3 They have a vasodilator effect, resulting in relaxation of vascular smooth muscle. There are three general classes of calcium antagonists: (1) phenylalkylamines such as verapamil, (2) benzothiazepines such as diltiazem, and (3) dihydropyridines such as nifedipine. 12 Calcium antagonists have been associated with dry mouth and gingival hyperplasia.3 Nifedipine, diltiazem, and verapamil have all been associated with gingival overgrowth.15

Hypertension is a serious problem in the United States, and medications used to treat it have definite side effects relative to the practice of dentistry. Dentists frequently encounter patients who are using one or more antihypertensive medications. The purpose of this study is to determine the incidence of active duty soldiers dispensed antihypertensive medications at a large military installation.

Materials and Methods

The study involved analysis of outpatient prescriptions at a large military installation (Fort Hood, Texas). The pharmacy serves a population of 41,491 active duty troops. A pharmacy computer system has the capability to list prescriptions by patient name, age, or sex and by drug name and class. Data were collected for a 2-month period (January and February 1997) without violation of privacy act provisions. A 2-month period should capture a cross-section of most patients who are receiving antihypertensive medications. The study was undertaken with the knowledge that some antihypertensive medications are prescribed for conditions other than hypertension. For example, beta-blockers may be used to treat angina, irregular heart rates, and migraine headaches.2 No attempt was made to identify patients prescribed multiple antihypertensive agents.

Results

A total of 627 prescriptions for antihypertensive medications were dispensed to active duty soldiers during the period January 1 to February 28, 1997, at Fort Hood, Texas. Data were evaluated in terms of (1) most frequently prescribed medications, (2) medications according to drug class, and (3) prescriptions for medications according to patient age and sex. Age groups in this study were based on physical performance age groups for running. The first two age groups in this study differed slightly from the average performance standards for the groups 18 to 20 years and 21 to 24 years.'6 The youngest subjects in this study were IS years old. Initial enlistment for most soldiers is 3 years. Therefore, the initial age group consisted of patients aged 18 to 20 years.

The antihypertensive medications are listed in Table I (the top 10 constitute 91.55% of all antihypertensive medications; N = 574). Lisinopril, an ACE inhibitor, tops the first 5, followed by hydrochlorothiazide (diuretic), amlodipine (calcium channel blocker), propranolol (nonselective beta-blocker), and felodipine (calcium channel blocker). The second 5 are verapamil (calcium channel blocker), atenolol (cardioselective beta-blocker), diltiazem (calcium channel blocker), terazosin (alpha-adrenergic blocker), and, in a tie for number 10, clonidine (central sympatholytic) and nifedipine (calcium channel blocker). The remaining 8.45% of prescriptions are divided among 19 different medications (N = 53). Most of the top-10 antihypertensive medications in this study fall into the following five drug classes: (1) calcium antagonists (34.5%), (2) ACE inhibitors (25%), (3) /-adrenergic blockers (16.6%), (4) diuretics (14%), and (5) a-blockers/central sympatholytics (9.9%).

At the time of the survey, the total active duty troop population was 41,491 (32,593 male, 8,898 female). Table II shows the active duty patient population by age group and gender. As would be expected in a large military population, the majority of troops were younger than 30 years of age and male (67.1% and 78.55%, respectively).

Basic demographic data were evaluated according to drug use by name and age group. Table III shows the most frequently prescribed antihypertensive drugs by age group for each sex. Table IV shows the data for all soldiers. The frequency of antihypertensive medication use by all soldiers younger than age 30 is 0.16% (11.6% for the group dispensed antihypertensive drugs). For males, the frequency of antihypertensive drug prescriptions approximately doubled each 4 years beginning with age 18 until age 40 (Table III). The greatest number of prescriptions were written for males older than 30 (N = 461). The number of prescriptions dispensed for the female population remains relatively consistent from age 30 and older.

In this study, 0.27% of females younger than 30 were prescribed an antihypertensive agent, and 1.87% of females older than 30 were prescribed an antihypertensive medication. Overall, 0.82% of the females in the population were prescribed an antihypertensive agent.

Of males prescribed an antihypertensive agent, 0.24% were younger than 30 and 4.3% were older than 30; 1.57% of the males in this population were prescribed an antihypertensive agent. Overall, 0.16% of all soldiers younger than 30 and 1.25% of soldiers older than 30 were prescribed an antihypertensive agent.

Table V shows the results of a pilot survey of active duty patients by age and sex and by departments (periodontics, endodontics, and prosthodontics). Dentists in these departments recorded each patient's sex and age at time of treatment. A pilot survey was undertaken to determine whether or not the patients treated in the departments of periodontics, prosthodontics, and endodontics reflected the overall gender and/or age of the post population (as seen in Table II) and whether or not the data would be helpful in determining the chances of a patient taking an antihypertensive medication in a particular department. A total of 471 patient visits were recorded over a 5-week period (331 male, 140 female). This represented 70.27% males and 29,73% females, which is similar to the gender percentage of the Fort Hood, Texas, population (78.55% male and 21.45% female; Table II). For males, the majority of patient visits in periodontics and prosthodontics were by soldiers older than 30 (82.66% and 63.76%, respectively). For females, 73.33% of visits in the periodontics department were by patients older than 30 and 81.97% of visits in prosthodontics were by patients older than 30. For both the male and female population, visits to the endodontics department did not show a specific age breakdown but were distributed evenly throughout the age groups, reflecting the general patient population.

Discussion

The Fort Hood pharmacy also senes a large retired population. For comparison, antihypertensive medications for the retired population were also evaluated during the same period. Lisinopril and hydrochlorothiazide were still the most commonly prescribed antihypertensive agents. Atenolol and diltiazem were in third and fourth place. respectively, and their use increased approximately 2-fold compared with the active duty survey. The remainder of the top 10 included amlodipine. terazosin. furosemide, verapamil, metoprolol, and felodipine. Thirty-five additional medications constituted the remainder of the sample (N = 4,924). The age range for the retired group was 24 to 95 years.

Examination of pharmacy records shows that for both the active duty and retired military population at Fort Hood. lisinopril was the most frequently prescribed antihypertensive drug, followed by hydrochlorothiazide, during January and February 1997. Four classes of drugs constituted the majority of the 10 most commonly prescribed medications for both the active duty and retired military populations. The calcium antagonists are the most commonly prescribed drug class. Diuretic use increased among the retired population compared with the active duty population: use of beta-blockers remained remarkably consistent among both groups. The 1997 JNC VI report indicates that stage 1 and 2 hypertension are usually treated with a single drug (often a diuretic or beta-blocker).7 Controlled clinical trials suggest the effectiveness of these drugs.17 Other drugs may be acceptable for monotherapy; they include calcium antagonists, ACE inhibitors, aIpha^sub 1^-receptor blockers and alphabeta-blockers. Results shown in Table I reaffirm that many of these drugs are currently in use among the military population at Fort Hood. Drug therapy is usually delayed until after lifestyle modifications have been shown to be ineffective. These modifications include weight reduction, increase in physical activity, and moderation of alcohol/sodium intake. Patients with stage 1 hypertension remaining after 12 months of monitored lifestyle modifications may require antihypertensive drug therapy.7 In the present study, most of the antihypertensive drugs for both the active and retired military populations fall into four categories: (1) calcium antagonists, (2) ACE inhibitors, (3) diuretics, and (4) beta-blockers. Knowledge of drug mechanisms of action and possible drug interactions is necessary to avoid possible adverse reactions while rendering dental treatment, Proper review of patient medical histories and regular blood pressure screenings are useful in identifying patients who may require further medical workup and possible treatment for hypertension. The dentist must be aware of possible interactions between medications commonly used in the dental clinic (local anesthetic with vasoconstrictors, NSAIDs for postoperative pain control) and drugs taken by patients to control hypertension. The results of this investigation have shown that antihypertensive agents such as lisinopril, hydrochlorothiazide, amlodipine, propranolol, felodipine. diltiazem, and atenolol are frequently prescribed to both active duty and retired soldiers at a large military installation.

In this study, 0.27% of active duty females younger than 30 and 1.87% of active duty females older than 30 were prescribed an antihypertensive medication. This percentage increased to 3.51% for all active duty females older than 40.

Similarly, 0.24% of active duty males younger than 30 and 4.3% of active duty males older than 30 were prescribed an antihypertensive drug. This percentage increased to 12.05% for all active duty males older than 40. In this study. active duty males older than 30 were more than twice as likely to be prescribed an antihypertensive medication than active duty females older than 30. Active duty males older than 40 were more than 3 times more likely to be prescribed an antihypertensive agent than active duty females in the same age group. Comparison of the incidence of antihypertensive medication prescriptions for active duty males younger than 30 and active duty males older than 40 showed that the older than 40 group was greater than 50 times more likely to be prescribed an antihypertensive agent than the younger than 30 group.

Recent evidence has suggested that periodontal disease may be a risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Drisko et al. found in a survey of 100 cardiovascular disease patients that 86% had periodontal disease. The authors suggested that further research was needed to explore periodontal disease as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease.18

In this survey, 0.16% of the active duty soldiers younger than 30 were prescribed an antihypertensive medication and 1.25% of active duty soldiers older than 30 were prescribed an antihypertensive agent. The prevalence of hypertension in the United States has been reported to increase as people age.2 The results of this survey demonstrated a similar trend. Schulz et al. also reported a prevalence of hypertension increasing from 15% in men age 30 to 39 years to 30% to 35% in men age 50 to 65 years.19 This survey suggested the prevalence of known hypertension (based on being prescribed an antihypertensive medication) to be 2.55% for men age 30 to 39 years; this increased to 12.05% for men older than 40 years. These percentages are lower than those found by Schulz et al. This may be attributable to the fact that the survey population was composed of soldiers who maintain better physical conditioning than the general population. The increase in the prevalence of hypertension with increasing age suggests that a patient treated for periodontal conditions or prosthodontic reasons tended to be older than 30 years of age. In the pilot study, 82.6% of the patients seen were older than 30 (Table V. These patients may be more likely to be taking an antihypertensive medication than patients treated for other dental conditions. Active duty male soldiers older than 40 are more than 50 times more likely to be prescribed an antihypertensive agent than active duty males younger than 30. The results of this survey suggest the need to correlate the possible relationship of hypertension and periodontal disease as a risk factor.

References

Lentz A, Kerns DG: Twenty commonly dispensed medications of a United States military installation and their significance to dentists. Milit Med 1995: 160: 5138.

2. Rose L, Kaye D: Internal Medicine for Dentistry, Ed 2, pp 413-20. St. Louis. MO. Mosby. 1990.

3. Little JW, Falace DA. Miller CS. Rhodus NL: Dental Management of the Medically Compromised Patient, Ed 5, pp 176-91. St. Louis, MO. Mosby. 1997. 4. Malamed SF: Handbook of Local Anesthesia. Ed 4, pp 37-48. St. Louis, MO, Mosby, 1997.

5. Neidle E. Kroeger D, Yagiela J: Pharmacology and Therapeutics for Dentistry. pp 124-39; 432-49. St. Louis, MO, Mosby, 1980.

6. The Fifth Report of the Joint National Committee on Detection, Evaluation. and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC V). Arch Intern Med 1993:153:154-69. 7. The Sixth Report of the Joint National Committee on Detection, Evaluation, and

Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC VIJ. Arch Intem Med 1997:157: 2413-46. 8. Mayo Clinic Family Health computer program. version 2.0. 1995. 9. Dupont AG: The place of diuretics in the treatment of hvpertension: a historical review of classical experience over 30 years. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 1993; I(suppl): 55-62.

10. Houston MC. Weir M, Gray J: The effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on patients with hypertension controlled by verapamil. Arch Intern Med 1995:155: 1049-54.

I1. Muzyka BC, Glick M: The hypertensive dental patient. J Am Dent Assoc 1997: 128:1109-20.

12. Nogueira da Costa J: Treatment of high blood pressure: from diuretics to the present and future. Cardiologia 1995: 40: 893-8. 13. Gage T. Pickett F: Dental Drug Reference. St. Louis, MO, Mosby, 1994. 14. Freis E. Papademetriou V: Current drug treatment and treatment patterns with antihypertensive drugs. Drugs 1996: 52: 1-16.

15. Silverstein LI. Garnick JJ, Szikman M. Singh B: Medication induced gingival enlargement. Gen Dent 1997:45: 371-6.

16. Rodgers B: Bill Rodgers Lifetime Running Plan. pp 244-5. New York. Harper

Collins, 1996.

17. Alderman MH: Which antihypertensive drugs first-and why. JAMA 1992: 267: 2786-7.

18. Drisko C, Peters P, Greenwell H. Hill M: Evaluation of a population with periodont/tis and cardiovascular disease: a pilot study labstract 14581. J Dent Res (Special Issue A) 1998: 77.

19. Schulz J, Schmidt J Rack W: The value of nifedipine in the treatment of hypertension. coronary heart disease, and myocardial infarction. Curr Med Res Opin 1996;13: 397-408.

Guarantor: Bernard J. Hennessy, DDS

Contributors: Bernard J. Hennessy, DDS; David G. Kerns, DMD MS; William G. Davies, RPh MS

U.S. Army Dental Activity. Billy Johnson Dental Clinic. Fort Hood, TX 76544-5063.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the U,S. Army or the Department of Defense.

Copyright Association of Military Surgeons of the United States Oct 1999

Provided by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights Reserved