Definition and Description

Symptoms of SLE

Diagnosis of SLE

Treatment of SLE

Medications for SLE

Psychosocial Aspects

Health Care Implications

Care for the patient with lupus erythematosus is a challenge that draws on all the resources, knowledge, and strengths the health care team has to offer. Because of the unpredictable, highly individualized, and frequently changing nature of the disease as well as the intricacy of each patient's needs, it is impossible to predict the treatment for one patient from the outcome of treatment for another. Careful listening to the person's concerns; a cooperative, multidisciplinary approach; and a flexible plan of care will provide the patient with consistent, supportive care and the reassurance that her or his needs are being attended to.

Definition and Description

Lupus means "wolf." Erythematosus means "redness." In 1851, doctors coined this name for the disease because they thought the facial rash that frequently accompanies lupus looked like the bite of a wolf. Lupus can be categorized into three groups: discoid lupus erythematosus, systemic lupus erythematosus, and drug-induced systemic lupus erythematosus.

Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) is characterized by a skin rash only. It occurs in about 20% of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. The lesions are patchy, crusty, sharply defined skin plaques that may scar. These lesions are usually seen on the face or other sun-exposed areas. DLE may cause patchy, bald areas on the scalp and hypopigmentation or hyperpigmentation in older lesions. Biopsy of a lesion will usually confirm the diagnosis. Topical and intralesional corticosteroids are usually effective for localized lesions; antimalarial drugs may be needed for more generalized lesions. DLE only rarely progresses to systemic lupus erythematosus.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE, or lupus) is a chronic, inflammatory, multisystem disorder of the immune system. Lupus: A Patient Care Guide for Nurses and Other Health Professionals is concerned primarily with this form of lupus. In SLE, the body develops antibodies that react against the person's own normal tissue. This abnormal response leads to the many manifestations of SLE and can be very damaging. The course is unpredictable and individualized; no two patients are alike. Lupus is not contagious, infectious, or malignant. It usually develops in young women of childbearing years, but many men and children also develop lupus. African Americans and Hispanics have a higher frequency of this disease than do Caucasians. SLE also appears in the first-degree relatives of lupus patients more often than it does in the general population, which indicates a strong hereditary component. However, most cases of SLE occur sporadically, indicating that both genetic and environmental factors play a role in the development of the disease.

Lupus varies greatly in severity, from mild cases requiring minimal intervention to those in which significant and potentially fatal damage occurs to vital organs such as the lungs, heart, kidney, and brain. The disease is characterized by "flares" of activity interspersed with periods of improvement or remission. A flare, or exacerbation, is increased activity of the disease process with an increase in physical manifestations and/or abnormal laboratory test values. Periods of improvement may last weeks, months, or even years. The disease tends to remit over time. Some patients never develop severe complications, and the outlook is improving for those patients who do develop severe manifestations.

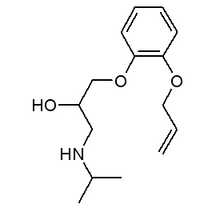

Drug-induced SLE develops after the use of certain drugs and has symptoms similar to those of SLE. The characteristics of this syndrome are pleuropericardial inflammation, fever, rash, and arthritis. Serologic changes also occur. The clinical and serologic signs usually subside gradually after the offending drug is discontinued. A wide variety of drugs is implicated in this form of SLE.

Drugs Implicated as Activators of SLE

Drugs with proven association

* Chlorpromazine

* Hydralazine

* Isoniazid

* Methyldopa

* Procainamide

Drugs with possible association

* Beta blockers (e.g., acebutolol, atenolol, labetalol, metoprotolol, oxprenolol, pindolol, practolol, and propranolol)

* Captopril

* Carbamazine

* Cimetidine

* Diphenylhydantoin (phenytoin)

* Ethosuximide

* Methimazole

* Penicillamine

* Phenazine

* Quinidine

From: The Bulletin on the Rheumatic Diseases, copyright 1991. Used by permission of the Arthritis Foundation. For more information, call the Arthritis Foundation's information line: 1-800-283-7800.

Symptoms of SLE

Early symptoms of SLE are usually vague, nonspecific, and easily confused with other pathological and functional disorders. Symptoms may be transient or prolonged, and individual symptoms often appear independently of the others. Moreover, a patient may have severe symptoms with few abnormal laboratory test results, and vice versa. A range of clinical symptoms are seen in patients with lupus over the lifetime of the disease.

Symptoms of SLE

* Arthralgia

* Arthritis

* Fever ([is greater than] 100 [degrees] F)

* Skin rashes

* Anemia

* Kidney damage

* Pleurisy

* Facial rash

* Photosensitivity

* Alopecia (hair loss)

* Raynaud's phenomenon

* Seizures

* Mouth or nose ulcers

Diagnosis of SLE

The onset of lupus may be acute, resembling an infectious process, or it may be a progression of vague symptoms over several years. As a result, diagnosing SLE is often a challenge. A consistent, thorough medical examination by a doctor familiar with lupus is essential to an accurate diagnosis. This must include a complete medical history and physical examination, laboratory tests, and a period of observation (possibly years). The doctor, nurse, or other health professional assessing a patient for lupus must keep an open mind about the varied and seemingly unrelated symptoms that the patient may describe. For example, a careful medical history may show that sun exposure, use of certain drugs, viral disease, stress, or pregnancy aggravates symptoms, providing a vital diagnostic clue.

No single laboratory test can definitely prove or disprove SLE. Initial screening includes a complete blood count (CBC), liver and kidney screening panels, laboratory tests for specific autoantibodies (e.g., antinuclear antibodies [ANA]), a syphilis test (VDRL), urinalysis, blood chemistries, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). Abnormalities in these test results will guide further evaluations. High-titer anti-nDNA antibody or anti-Sm antibody are important indications of lupus. Specific immunologic studies, such as those of complement components (e.g., C3 and C4) and other autoantibodies (e.g., anti-La and anti-Ro), are used to help evaluate the patient's immune status and to monitor the activity of the disease. At times, biopsies of the skin or kidney using immunofluorescent staining techniques can support a diagnosis of SLE (see Chapter 3, Laboratory Tests Used to Diagnose and Evaluate SLE, for further information). A variety of laboratory tests, X rays, and other diagnostic tools are used to rule out other pathologic conditions and to determine the involvement of specific organs. It is important to note, however, that any single test may not be sensitive enough to reflect the intensity of the patient's symptoms or the extent of the disease's manifestations.

The American College of Rheumatology (ACR), an organization of doctors and associated health professionals who specialize in arthritis and related diseases of the bones, joints, and muscles, has developed and refined a set of diagnostic criteria. If at least 4 of the 11 criteria develop at one time or individually over any period of observation, then the patient is likely to have SLE. However, a diagnosis of SLE can be made in a patient having fewer than four of these symptoms.

ACR Criteria for Diagnosing SLE

* Malar rash

* Discoid rash

* Photosensitivity

* Oral ulcers

* Arthritis

* Serositis (pleuritis or pericarditis)

* Renal disorder (persistent proteinuria or cellular casts)

* Neurological disorder (seizures or psychosis)

* Hematologic disorder (anemia, leukopenia or lymphopenia on two or more occasions, thrombocytopenia)

* Immunologic disorder (positive LE cell preparation, abnormal anti-DNA or anti-Sm values, false-positive VDRL syphilis test)

* Abnormal ANA titer

Source: Tan E. The 1982 required criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis and Rheumatism 1982;25:1271-1277. [C] 1982 American College of Rheumatology. Used with permission of Lippincott-Raven Publishers.

Treatment of SLE

The treatment of SLE is as varied as its course. Although there is no cure for lupus and it is difficult to predict which treatment will be most effective for each patient, there have been significant gains in treating patients, and there is general consensus on several treatments.

A conservative regimen of physical and emotional rest, protection from direct sunlight, a healthful diet, prompt treatment of infections, and avoidance of known allergens and aggravating factors are the mainstays of lupus therapy. In addition, for female patients, pregnancy must be planned for times when the disease is in remission.

Physical Rest

This basic component of everyone's good health is essential for the lupus patient. The fatigue of lupus is not sleepiness or tiredness from physical exertion, but rather a frequent, persistent complaint often described as a "bone-tired feeling" or a "paralyzing fatigue." Normal rest often does not refresh the patient or eliminate the tiredness due to lupus, and fatigue may persist despite normal laboratory test results. The patient and family need instruction on how to use this tiredness as a guide to activity and when the person should stop for rest. It must be reinforced that this need for rest is not laziness. Restful sleep of 8-10 hours per night, naps, and "timeouts" during the day are basic guidelines; strict bed rest is usually not required. Physical activity should be encouraged as the patient can tolerate it. An individualized exercise routine may facilitate recovery from a flare and promote well-being.

Emotional Rest

A patient's emotional stressors should be carefully assessed, because they may play a role in triggering a flare. The patient should be instructed on how to avoid these stressful situations. However, the physical manifestations of lupus must be treated as they present themselves while the emotional stresses are explored. Discussions with the family on this issue are essential for providing information and in obtaining their support. Counseling for both the patient and the family may be an option. Chapter 6, Psychosocial Aspects of Lupus, explores these issues in further detail.

Protection From Direct Sunlight

Photosensitivity is an abnormal reaction to the ultraviolet (UV) rays of the sun and results in the development or exacerbation of a rash that is sometimes accompanied by systemic symptoms. About one-third of lupus patients are photosensitive. All lupus patients should avoid direct, prolonged exposure to the sun. Sun-sensitive patients should frequently apply a sunscreen with a Sun Protection Factor (SPF) of at least 15, avoid unprotected exposure between 10 a.m. and 4 p.m., and wear protective clothing, such as wide-brimmed hats and long sleeves. Lupus patients should be aware that UV rays are reflected off water and snow, and that glass, such as car windows, does not provide total protection from UV rays.

Lupus patients should also know that fluorescent and halogen lights may emit UV rays and can aggravate lupus. This may be an issue for patients who work in offices lit by these kinds of lights. Sunscreen and protective clothing can help minimize exposure, and plastic devices are available that block UV emissions from fluorescent or halogen light bulbs.

Diet and Nutrition

A well-balanced diet is essential in maintaining good health for all people, including lupus patients. There are currently no specific dietary recommendations or limitations for those with lupus, but a restricted diet plan may be prescribed when fluid retention, hypertension, kidney disease, or other problems are present. Food intolerances and allergies may occur, but there is no evidence that these are more common in lupus patients than in the general population. The health professional should make a note of the patient's dietary history and suggest diet counseling if appropriate, especially if the patient has a problem with weight gain, weight loss, gastrointestinal (GI) distress, or food intolerances. Nutritional considerations in treating lupus patients are discussed further in Chapter 4, Care of the Lupus Patient.

Treatment of Infections

Prompt recognition and treatment of infection is essential for those with lupus. However, cardinal signs of infection may be masked because of SLE treatments. For example, a fever may be suppressed because anti-inflammatory therapy is being given. When an infection is being treated, the health professional should be alert to medication reactions, especially to antibiotics.

Pregnancy and Contraception

Spontaneous abortion and premature delivery are more common for women with SLE than for healthy women. To minimize risks to both mother and baby, a pregnant woman with lupus should be closely supervised by an obstetrician familiar with lupus. The safety of oral contraceptives for women with lupus is currently under investigation. The use of an intrauterine device (IUD) is not recommended because of the lupus patient's increased risk of infection.

Surgery

Surgery may exacerbate the symptoms of SLE. Hospitalization may be required for otherwise minor procedures, and postoperative discharge may be delayed. If it is elective, the surgery (including dental surgery and tooth extraction) should be postponed until lupus activity subsides.

Immunizations

Immunizations with killed vaccines have not been shown to exacerbate SLE. However, live vaccines with attenuated organisms are not advisable. A lupus patient should consult her or his doctor before receiving any immunizations, even routine ones.

Medications for SLE

SLE management should include as few medications for as short a time as possible. Some patients never require medications, and others take them only as needed or for short intervals, but many require constant therapy with variable doses. Despite their usefulness, no drugs are without risks. Medications frequently used to control the symptoms are nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), antimalarials, corticosteroids, and immunosuppressives. Other medications may be necessary to control specific manifestations. Before prescribing a medication, it is helpful to scrutinize a patient's past response to treatments. A careful drug history should be taken; in particular, hypersensitivities or allergies to certain drugs should be noted, as these may aggravate the lupus. Patient and family education about medications and their side effects is essential. Chanter 5, Medications Used To Treat Lupus, presents more detailed information on this issue, and Chapter 7, Patient Information, includes relevant information for patients.

Psychosocial Aspects

For the lupus patient, the emotional aspects of dealing with a chronic disease can be overwhelming. They can also make a patient feel isolated from friends, family, and coworkers. Grief, depression, and anger are common reactions of patients about their lupus.

Lupus patients and their families deal with the disease in strikingly different ways. Managing the ups and downs of the disease may put strains on relationships and marriages. Younger patients may fail to assert their independence or develop a life away from home if they feel they cannot cope with their disease on their own. Family members are often confused and frightened over the changes they see and need guidance and constructive suggestions on helping the patient. Children of lupus patients, particularly those too young to really understand the disease, may need special help in coping with their parent's illness. It is in these areas that the patient, family, and support systems need to be assessed, encouraged, and guided so that they work together as a team. Allowing the patient and her or his family time and freedom to move through different emotional phases without criticism and unrealistic expectations will facilitate acceptance of the disease. The health professional can have a major role in helping a patient adjust and can help with referrals to a social worker, counselor, or community resource, if needed. Chapter 6, Psychosocial Aspects of Lupus, discusses these issues in more detail.

Health Care Implications

How lupus is defined, diagnosed, and treated and the psychosocial issues involved have implications for the way that the nurse or other health professional works with a patient who has lupus. For example, a newly diagnosed lupus patient needs help in getting current, accurate information about the disease and in defining realistic expectations and goals. The Patient Information Sheets in Chapter 7, can help. The health professional can clarify information with the patient's doctor, make rounds with the doctor, and act as a liaison between the patient and the doctor, if needed. Frequently, many doctors are involved in caring for a lupus patient at one time. This may increase the patient's confusion and leave gaps in information. Emotional support to the patient is essential. Being available for questions, providing reassurance, and encouraging discussion of fears and anxieties are all crucial roles that the nurse can play.

The lupus patient hospitalized during a flare requires symptomatic nursing care. It is important to note that objective data, such as anemia or sedimentation rate, may not support subjective complaints of fatigue or pain. Careful head-to-toe assessment and documentation of all symptoms and complaints are important. Symptomatology changes constantly, so frequent reassessment is necessary. Reevaluations validate a patient's concerns and alert the doctor to changes that may be transient yet significant.

The patient's tolerance for physical activity and need to control what she or he can do should be respected. The patient should be involved in developing a care plan and daily schedule of activities.

The best way to treat lupus is to listen to the patient, whether that patient was diagnosed today or years ago. The patient's support systems can be expanded to include pamphlets and books, physical or occupational therapy, vocational rehabilitation, homemaker services, the Visiting Nurses Association (VNA), the Lupus Foundation of America (LFA), and the Arthritis Foundation (AF).

Lupus is a challenge to everyone concerned. The health professional has a key role in its management. Accurate documentation, supportive care, emotional support, patient education, and access to community resources will provide the patient and her or his family with the tools they need to cope effectively.

Outline Credits Acknowledgments Introduction PDF Order Form Home

1. Erythematosus 2. Advances 3. Tests 4. Care 5. Medications 6. Psychosocial Aspects 7. Patient Info. 8. Resources

National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS) National Institutes of Health (NIH) Bethesda, Maryland 20892-2350

January 26, 1999

COPYRIGHT 1999 National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group