Complications of Phenylpropanolamine Phenylpropanolamine is a sympathomimetic agent present in over 100 proprietary and prescription anorectics, nasal decongestants, psychostimulants and treatments for premenstrual syndrome. It is often found in street drugs prepared to look like amphetamines. Phenylpropanolamine has precipitated paranoid psychosis, severe anxiety, cerebrovascular accidents and hypertensive crises. Hypertensive crises can be treated with phentolamine. Pyschiatric symptoms and anxiety are managed with benzodiazepines. Phenylpropanolamine, a common ingredient in many prescription and over-the-counter medications, is not a benign compound.(1-4) It can cause severe death when it is unknowingly ingested by a person who is sensitive to it or who may consume more than the recommended dosage.

On the street, phenylpropanolamine may be sold and substituted for, or combined with, amphetamine. However, a person need not buy illicit drugs to be at risk for adverse reactions. It is important that physicians and laypersons know which preparations (especially diet aids and decongestants) contain this agent. Phenylpropanolamine ingestion must always be included in the differential diagnosis and management of psychoses, seizures, strokes and hypertension.

Pharmacology

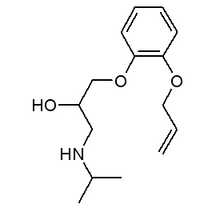

The structures of phenylpropanolamine, amphetamine, ephedrine and metaraminol. Phenylpropanolamine is a potent, relatively selective Alpha1-receptor agonist. Although it is primarily a direct-acting agonist, it also causes release of norepinephrine. Thus, it is much like metaraminol, an agent that differs only by the presence of a hydroxyl group on the phenyl ring. Phenylpropanolamine's effect on the central nervous system is modest compared to that of amphetamine and ephedrine. It is, however, a more potent activator of peripheral Alpha1 receptors than these other compounds.(5)

Phenylpropanolamine is only a weak Beta-adrenergic agonist. This property, coupled with its potent Alpha1 receptor effects, renders it a potent pressor agent when compared with other drugs in its class. Hypertension associated with phenylpropanolamine is often accompanied by a reflex bradycardia.(5) when tachycardia occurs, it is usually the result of concomitant drug use, such as an antimuscarinic agent, another sympathomimetic agent or a xanthine derivative.

Both isomers of phenylpropanolamine are active, but the dextrorotatory form is a significantly more potent sympathomimetic agent. In most countries, the racemic form is the only one marketed.

PHARMACOKINETICS

The prompt-release form of the oral preparation of phenylpropanolamine is rapidly absorbed; most clinical effects occur within three hours of ingestion. In cases of overdose, the duration of toxic side effects is usually less than six hours, which is consistent with an elimination half-life of three to four hours. Extended-release preparations have slightly delayed peak levels. Pharmacologically significant concentrations persist as long as 16 hours. Eighty to 90 percent of the drug is excreted unchanged in the urine within 24 hours; small amounts are slowly metabolized to an active hydroxylate metabolite.(6)

Complications

Numerous prescription drugs contain phenylpropanolamine in combination with other agents.(4,6) The signs and symptoms produced by this chemical usually involve the cardiovascular system (hypertension is the most commonly associated sign) and the central nervous system, including psychiatric manifestations.

The incidence of phenylpropanolamine-associated symptomatology is not known. It is important for physicians to notify the Food and Drug Administration when morbidity is believed to result from this agent. This will provide a better estimate of the public health problem posed by phenylpropanolamine and allow a more informed decision about its suitability as an over-the-counter compound.

Since 1980, at least 131 adverse reactions involving phenylpropanolamine, including 12 deaths, have been reported to the FDA. It is recommended that phenylpropanolamine be used with caution in patients with hyperthyroidism, cardiovascular disorders (including hypertension) or diabetes mellitus. Adverse reactions may also occur in patients taking monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitors, indomethacin (Indocin) and, possibly, other prostaglandin synthesis inhibitors, methyldopa (Aldomet), beta blockers, sympathomimetic amines, xanthine preparations or antimuscarinic agents.(7-10) However, concurrent use of these drugs and phenylpropanolamine does not entirely account for the numerous reports of adverse reactions that appear in the literature.

Cardiovascular toxicity is the most common medical complication induced by phenylpropanolamine. Although 50 mg of phenylpropanolamine increases blood pressure only slightly in young, normotensive subjects,(11) the drug has an extremely low therapeutic index. Severe hypertensive reactions, often associated with throbbing, bilateral headache, may be produced at doses less than three times the usual over-the-counter dose of 37.5 mg.(11,12) Some patients may be at increased risk for adverse reactions--for example, patients with autonomic dysfunction and postural hypotension. They may exhibit severe hypertension in response to even small doses of phenylpropanolamine, whether it is used alone or in combination with other agents.(12)

Hypertension is the most frequently reported adverse reaction, but other organ systems may also be affected. In addition to seizures, paresthesias and tremors, there are reports of fatal strokes following phenylpropanolamine ingestion.(13-19) Acute renal failure and rhabdomyolysis have also been documented.(20)

Paranoid psychosis appears to be the most common psychiatric phenomenon, but other psychiatric symptoms associated with the ingestion of phenylpropanolamine include deja vu experiences, persecutory delusions, auditory and visual hallucinations and manic-like states.(21-26) The psychosis often persists after the cessation of phenylpropanolamine use and may be more likely to occur in those individuals who are predisposed to psychiatric illness. Symptoms may be aggravated by the concomitant use of other medications, such as cold remedies, antimuscarinic agents and psychostimulants. Medications containing pseudoephedrine have less effect on the central nervous system and may represent a better choice for the psychiatric patient at risk for sympathomimetic-precipitated psychosis. Antihistamines, belladonna alkaloids or decongestants are also therapeutic options.

Treatment Guidelines

Hypertensive crises produced by phenylpropanolamine can be rapidly treated with phentolamine (Regitine), an Alpha1-receptor antagonist, or sodium nitroprusside (Nipride). Nifedipine (Adalat, Procardia) or chlorpromazine (Thorazine) may be effective in less urgent situations.

Ventricular ectopy due to phenylpropanolamine has been reported to respond to lidocaine (Xylocaine)(27) or propranolol (Inderal).(28) Atrial and ventricular tachycardias may be responsive to Beta-adrenergic blocking agents,(28) but these drugs may occasionally accentuate the hypertensive properties of phenylpropanolamine, because of unopposed Alpha1-receptor blockade. Thus, blood pressure must be carefully monitored when a beta blocker is used to treat these arrhythmias. This precaution is warranted even when labetalol (Normodyne, Trandate), which blocks both Alpha-and Beta-adrenergic receptors, is used to treat arrhythmias or hypertension. Phentolamine has weak Beta- and potent Alpha1-adrenergic antagonist properties that may prevent the development of hypertension, and it can be administered in conjunction with a Beta-adrenergic blocking agent.(29)

Severe hypertension can precipitate seizures. Patients with seizures as a result of phenylpropanolamine are treated initially with intravenous benzodiazepines, followed by a loading dose of phenytoin (Dilantin).(14,15) A single convulsion in the clinical setting of phenylpropanolamine intoxication is not thought to be an indication for indefinite treatment with anticonvulsants.

Anxiety induced by phenylpropanolamine can be treated much the same as that of amphetamine intoxication--with orally or parenterally administered benzodiazepines.(30) Chouinard and associates(31) used oral clonazepam in the treatment of hypomanic and manic subjects who would normally receive a neuroleptic drug. Clonazepam (Klonopin) seems to be a reasonable choice for treatment of the hyperactivity, sleeplessness and panic produced by phenylpropanolamine. Daily doses in the range of 4 to 16 mg are recommended.(30) Parenteral clonazepam is not available; therefore, if a parenteral route of administration is necessary, diazepam (Valium) or lorazepam (Ativan), intramuscularly or intravenously, are therapeutic alternatives. These agents are also rapidly absorbed when given orally; clonazepam is not.

Since psychotic symptoms often remit spontaneously, it is not advisable to leave patients with phenylpropanolamine-related symptoms on antipsychotic agents indefinitely. The appropriate treatment may include drug "washout" (waiting for the body to clear the substance on its own) and observation. An asymptomatic patient with a past medical history of a psychotic disorder, such as schizophrenia or mania, may suddenly manifest psychotic symptoms as a result of phenylpropanolamine ingestion. Such episodes may require treatment with an antipsychotic drug. REFERENCES (1)Huff BB, ed. Physicians' desk reference. 42d ed. Oradell, N.J.: Medical Economics, 1988. (2)Handbook of nonprescription drugs. 7th ed. Washington, D.C.: American Pharmaceutical Association, 1982:160,342,695,823-5. (3)Kastrup EK, ed. Facts and comparisons. St. Louis: Facts and Comparisons Division, Lippincott, 1986:334-5,363,823. (4)Pentel P. Toxicity of over-the-counter stimulants. JAMA 1984;252:1898-903. (5)Weiner N. Norepinephrine, epinephrine, and the sympathomimetic amines. In: Gilman AG, ed. Goodman and Gilman's The pharmacological basis of therapeutics. 7th ed. New York: Macmillan, 1985:149. (6)McEvoy GK, ed. American Hospital Formulary Service drug information 87. Bethesda, Md.: American Society of Hospital Pharmacists, 1987. (7)Cuthbert MF, Greenberg MP, Morley SW. Cough and cold remedies: a potential danger to patients on monoamine oxidase inhibitors. Br Med J 1969;1(641):404-6. (8)Lee KY, Beilin LJ, Vandongen R. Severe hypertension after ingestion of an appetite suppressant (phenylpropanolamine) with indomethacin. Lancet 1979;1(8126):1110-1. (9)McLaren EH. Severe hypertension produced by interaction of phenylpropanolamine with methyldopa and oxprenolol. Br Med J 1976;2(6030):283-4. (10)Rumack BH, Anderson RJ, Wolfe R, Fletcher EC, Vestal BK. Ornade and anticholinergic toxicity: hypertension, hallucinations, and arrhythmias. Clin Toxicol 1974;7:573-81. (11)Horowitz JD, Lang WJ, Howes LG, et al. Hypertensive responses induced by phenylpropanolamine in anorectic and decongestant preparations. Lancet 1980;1(8159):60-1. (12)Biaggioni I, Onrot J, Stewart CK, Robertson D. The potent pressor effect of phenylpropanolamine in patients with autonomic impairment. JAMA 1987;258:236-9. (13)Mueller SM. Neurologic complications of phenylpropanolamine use. Neurology 1983;33:650-2. (14)Howrie DL, Wolfson JH. Phenylpropanolamine-induced hypertensive seizures. J Pediatr 1983;102:143-5. (15)Deocampo PD. Convulsive seizures due to phenylpropanolamine. J Med Soc N J 1979;76:591-2. (16)Mueller SM, Solow EB. Seizures associated with a new combination "pick-me-up" pill [Letter]. Ann Neurol 1982;11:322. (17)King J. Hypertension and cerebral haemorrhage after trimolets ingestion [Letter]. Med J Aust 1979;2:258. (18)Bernstein E, Diskant BM. Phenylpropanolamine: a potentially hazardous drug. Ann Emerg Med 1982;11:311-5. (19)Kikta DG, Devereaux MW, Chandar K. Intracranial hemorrhages due to phenylpropanolamine. Stroke 1985;16:510-2. (20)Swenson RD, Golper TA, Bennett WM. Acute renal failure and rhabdomyolysis after ingestion of phenylpropanolamine-containing diet pills. JAMA 1982;248:1216. (21)Norvenius G, Widerlov E, Lonnerholm G. Phenylpropanolamine and mental disturbances [Letter]. Lancet 1979;2(8156-8157):1367-8. (22)Achor MB, Extein I. Diet aids, mania, and affective illness [Letter]. Am J Psychiatry 1981;138:392. (23)Schaffer CB, Pauli MW. Psychotic reaction caused by proprietary oral diet agents. Am J Psychiatry 1980;137:1256-7. (24)Wharton BK. Nasal decongestants and paranoid psychosis. Br J Psychiatry 1970;117:439-40. (25)Kane FJ Jr, Green BQ. Psychotic episodes associated with the use of common proprietary decongestants. Am J Psychiatry 1966;123:484-7. (26)Lambert MT. Paranoid psychoses after abuse of proprietary cold remedies. Br J Psychiatry 1987;151:548-50. (27)Peterson RB, Vasquez LA. Phenylpropanolamine-induced arrhythmias. JAMA 1973;223:324-5. (28)Weesner KM, Denison M, Roberts RJ. Cardiac arrhythmias in an adolescent following ingestion of an over-the-counter stimulant. Clin Pediatr [Phila] 1982;21:700-1. (29)Duvernoy WF. Positive phentolamine test in hypertension induced by a nasal decongestant. N Engl J Med 1969;280:877. (30)Dietz AJ Jr. Amphetamine-like reactions to phenylpropanolamine. JAMA 1981;245:601-2. (31)Chouinard G, Young SN, Annable L. Antimanic effect of clonazepam. Biol Psychiatry 1983;18:451-66.

COPYRIGHT 1989 American Academy of Family Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group